How Do We Form Habits? Psychology Behind Our Daily Behaviors

Introduction

Habits dominate much of our daily life. Psychologists estimate that around 40% of our day-to-day actions are habitual – performed in the same contexts, on autopilot, without much deliberation. From the way you brush your teeth to the route you drive to work, countless behaviors turn into routine habits over time. But what exactly is a habit, and why do we form them? In simple terms, a habit is a learned behavior that becomes automatic: it’s an association between a contextual cue (like a place, time, or feeling) and a response (an action) that has been repeated so often the brain does it with little or no conscious thought. Habits arise because our brains are wired to spot patterns and repeat behaviors that reward us, which makes life more efficient. By offloading frequent tasks to “autopilot,” we free up mental energy for other things. This is incredibly useful – until an unwanted habit (say, mindlessly snacking when stressed) gets “wired in” alongside the useful ones. In this article, we’ll explore how habits form, the psychology and neuroscience behind them, common triggers that cue our habits, and evidence-based insights on changing habits – both breaking bad habits and building better ones.

Habit Formation 101: Why and How We Form Habits

Habits form through repetition and learning. Whenever you repeat an action in a stable context and it consistently yields a rewarding or desired outcome, your brain starts to automate that behavior. For example, if every morning you grab a coffee and feel more alert afterward, you begin to associate the sights and smells of morning (the context cues) with that energizing reward. Over time, just walking into the kitchen or passing your favorite café can trigger a craving for coffee and put you on “auto-pilot” to get a cup. In psychological terms, habits are a form of associative learning: we form mental links between stimuli and responses – often a cue and a behavior – especially when a reward or relief follows the behavior. We tend to “repeat what works”, so any action that helps us reach a goal (or feel good) in a given situation is likely to be repeated in that same situation again. Do it enough times, and the context itself will evoke the response habitually, even if you’re not consciously pursuing the original goal.

Classic learning theory laid the groundwork for understanding habits over a century ago. Ivan Pavlov’s dogs famously learned to drool upon hearing a bell, after the bell had been paired with delicious food repeatedly. This classical conditioning showed how neutral cues can come to automatically trigger responses. Similarly, B.F. Skinner’s research on operant conditioning demonstrated that behaviors followed by rewards become more likely to recur. Habits encapsulate both principles: through repetition, a previously neutral cue (like sitting on the couch at 9pm) can trigger a craving or response (reaching for a late-night snack) because your brain remembers that snack brought pleasure before. In essence, neurons that fire together wire together – repeated pairing of a context and an action strengthens the neural pathway linking them, making the behavior quicker and more automatic in that context (a neuroplastic process often summed up as Hebbian learning).

Notably, habits don’t require the reward to stay effective forever. Once a habit is ingrained, the context-cue can trigger the action even if the original reward is diminished or gone. This is why researchers in the field describe habits as “autonomous of the current value of the outcome”. In other words, you might continue a habit out of routine even when it no longer makes logical sense. A classic example comes from a study where moviegoers were given stale, week-old popcorn – people who had a movie-time popcorn-eating habit ate just as much stale popcorn as those given fresh popcorn, simply because the context (sitting at a cinema) cued their usual popcorn-eating routine. Their “thoughtful” brain knew the popcorn was bland, but their “habitual” brain was in charge, carrying out the learned behavior automatically. Habits, by design, bypass full conscious oversight. This makes them efficient (we don’t have to rethink every step of familiar tasks) but also potentially maladaptive if our circumstances change. An action that was beneficial or enjoyable in the past can become a mindless bad habit if we keep doing it on autopilot despite negative outcomes.

So, how do we intentionally form a new habit? The recipe is straightforward in theory: pick a behavior, and repeat it consistently in the same context, with a satisfying reward. Do this enough, and the behavior should start to become second-nature. Of course, in practice it’s not so simple – motivation, stress, and environment all influence whether we stick to a routine long enough to “wire” it in. Research has debunked the old myth that it takes just 21 days to form a habit; in reality, it can vary widely. One famous study found the average was about 66 days for a new behavior to feel automatic, though individual cases ranged from roughly 2 months to 8+ months. The takeaway: consistency is key, and it’s okay if a habit takes longer to stick – persistence will eventually rewire your brain.

Where Do Our Habits Come From?

Habits often form without us actively intending them. While you can deliberately cultivate habits (like practicing piano daily until it becomes habitual), many habits emerge unconsciously as we go through life. They can develop from repeating actions that meet some need or alleviate some discomfort. For example, a child who receives praise (reward) for cleaning up their room may slowly develop a tidy-up habit. Someone who finds that eating ice cream relieves boredom or stress might, without realizing it, link feelings of boredom with reaching for a sweet treat – a habit loop is born. Over time, emotional states can become internal triggers for habitual behaviors (bored? -> snack, anxious? -> bite nails, etc.). Similarly, external situations can breed habits: arriving home might trigger a routine of checking social media, or hearing your morning alarm might cue a cascade of habitual actions (making coffee, showering, etc.) that require no deliberation.

Our social and cultural environment is another source of habits. We tend to adopt behaviors we see regularly. As children, we unconsciously absorb habitual routines from parents and peers – how to greet others, how often to brush teeth, whether we exercise or not. These imitative habits can stick into adulthood. Even national or regional cultures shape habit norms (consider the habitual tea time in one culture versus a habitual siesta in another). Evolutionary psychology also suggests that our capacity to form habits has deep roots: early humans who turned important behaviors into habits (for finding food, shelter, safety) could perform them consistently with less mental effort, which was an advantage. Thus, our brains today want to automate frequent tasks.

Importantly, habits are reinforced by reward – but the “reward” isn’t always a positive one like pleasure; it can be the removal of a negative feeling. For instance, procrastination can become a habit because avoiding a tough task gives immediate relief from anxiety, which rewards the avoidance. Likewise, smoking can become a habit partly because it relieves nicotine withdrawal or stress. In each case, the loop is the same: a cue (feeling stressed) triggers a routine (smoke a cigarette), which produces a reward (stress relief) – and thus a habit forms. Some habits begin as coping mechanisms, formed during times of stress or emotional need. The downside is those habits tend to stick around even if they create other problems long-term.

Essentially then, our habits come from our experiences. They are baked by repetition, whether that repetition is intentional (practicing piano daily) or unintentional (snacking whenever boredom strikes). They’re influenced by what we find rewarding, what we see others do, and how our brains naturally try to simplify our lives. Understanding where a habit comes from – the need it’s meeting or the context that fostered it – is often the first step to changing it.

The Habit Loop: The Four Stages of Habit Formation

The habit formation process is often broken down into a loop of stages. A popular framework (notably described in the book Atomic Habits by James Clear) describes four key stages of every habit.

1. Cue – the trigger that initiates the habit. It’s a cue or reminder that tells your brain to go into automatic mode and prompts a behavior. A cue could be an external signal (like seeing a donut box, or a specific time of day) or an internal state (like feeling lonely or anxious). Essentially, the cue answers the question: “When/where does the habit occur?”

2. Craving – the desire or motivational force the cue provokes. The cue doesn’t automatically make you perform the habit; it first makes you want something. In habit loops, a craving is usually a craving for the reward or the change in state you expect. It’s the anticipation that drives you to act. (If the cue is seeing a donut box, the craving might be “I want that sweet pleasure”; if the cue is feeling lonely, the craving might be for comfort or distraction.)

3. Response – the habitual behavior itself. This is the routine or action you take when faced with the cue and experiencing the craving. It could be a thought or an action. The response is the part we typically recognize as “the habit” – e.g., eating the donut, scrolling through your phone, going for a run, etc.

4. Reward – the benefit you gain from the action, reinforcing the habit. This could be tangible (tasty sugar rush from the donut) or intangible (feeling relaxed after a run, or relief from boredom after checking your phone). The key is that the reward satisfies the craving from stage 2. It also feeds back into the loop: the brain registers that “when cue X happens, doing response Y leads to reward Z”. This reward feedback is what cements the habit, as it teaches your brain that the routine is worth remembering for the future.

Over time, these four stages merge into a powerful automated cycle. The brain learns to expect the reward as soon as the cue is noticed, which is why you can feel a craving or urge before you even carry out the habit. For instance, imagine you always eat a cookie at lunch. Just walking into the cafeteria (cue) might already make your mouth water for a cookie (craving) because your brain predicts the sugary reward. You then buy the cookie (response) and enjoy it (reward), further reinforcing the loop. Notably, if any link in this chain is broken, the habit won’t form or will fade – for example, if the reward disappears and no longer satisfies you, eventually the craving and response might dwindle.

Many experts simplify this process into a “cue → routine → reward” habit loop. In fact, the classic research by psychologist Charles Duhigg describes habits in three stages: a cue triggers a routine which is rewarded. The four-stage model is very similar; it simply highlights the role of craving (motivation) as an intermediate step between cue and action. In practice, whether we say three stages or four, the core idea is the same: something triggers us, we follow a learned routine, and there’s a payoff that reinforces doing it again. Understanding your own habits in these terms can be illuminating. You can ask: “What triggers this behavior? What reward am I really seeking?” Often, that insight is the first step toward changing the habit.

How the Brain Creates Habits: The Neuroscience of Automatic Behavior

What happens in your brain when a habit forms? Modern neuroscience has revealed that habits are encoded in ancient, deeper structures of the brain. A region called the basal ganglia – particularly the dorsolateral striatum, a part of the basal ganglia – is known to play a key role in habit formation and storage. This region coordinates with our motor system and decision-making areas. When you first learn a new behavior, you typically engage your prefrontal cortex (the “thinking” part of the brain) to make conscious decisions. But as you repeat the behavior over and over, especially in a consistent context, the control of the behavior seems to shift deeper into the brain – from the cortical (conscious) level to subcortical (automatic) level. In essence, the brain “hands off” the task to the habit system in the basal ganglia, which can run the behavior on autopilot without taxing your higher reasoning centers.

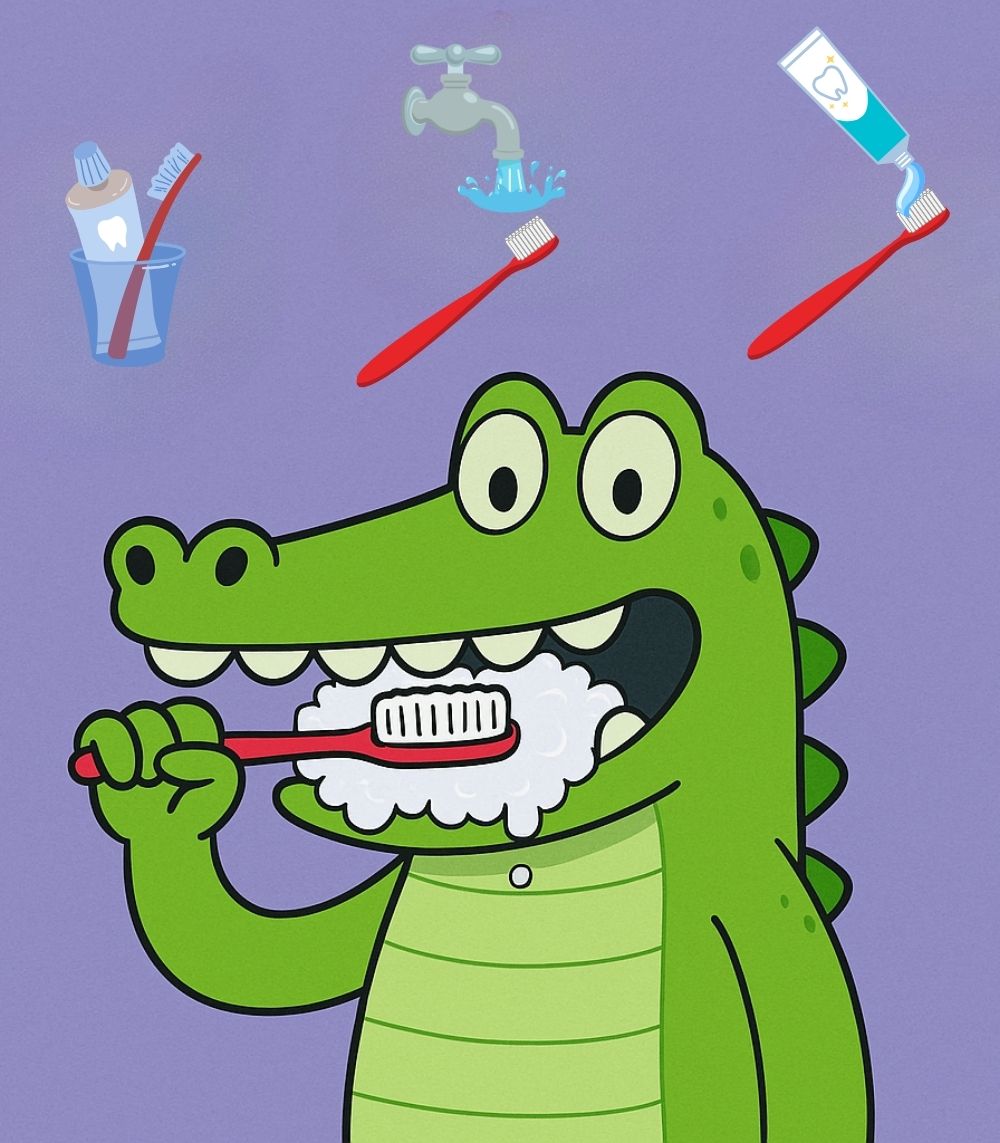

Neuroscientists have even observed specific neural signatures of habits forming. For example, research at MIT found that as rats learned a habit (running a maze for a reward), their brain activity in the striatum changed from being active throughout the task to firing only at the beginning and end of the routine. It’s as if the brain brackets the entire sequence of actions into one “chunk.” This phenomenon is aptly called “task bracketing.” Essentially, once a sequence (like brushing your teeth) is habitual, the brain treats the whole sequence as a single unit – it fires at the start to initiate the routine, then goes quiet, and fires at the end to mark it complete. You don’t consciously think of each step (pick up toothbrush, apply toothpaste, etc.) as separate decisions anymore. (In the illustration below, a simple routine like brushing teeth is composed of multiple sub-actions, but all together they form one happy habitual ritual.)

Illustration: A simple habit like brushing your teeth actually “chunks” many small actions (picking up the toothbrush, turning on the tap, applying toothpaste) into one smooth routine. Our brains encode habitual sequences as single units, firing neurons at the start and end of the routine – a neural “task bracketing” that makes the whole sequence automatic.

Illustration: A simple habit like brushing your teeth actually “chunks” many small actions (picking up the toothbrush, turning on the tap, applying toothpaste) into one smooth routine. Our brains encode habitual sequences as single units, firing neurons at the start and end of the routine – a neural “task bracketing” that makes the whole sequence automatic.Underlying these changes is the brain’s remarkable neuroplasticity – its ability to rewire connections with experience. With repetition, the neural pathways for a behavior get stronger and more efficient (hence the saying “practice makes permanent”). When a habit forms, connections between the cue centers and action centers of the brain become strengthened so that the cue can trigger the action quickly. Some of this involves the neurotransmitter dopamine, which spikes in the brain’s reward circuit when we get an unexpected reward. As a habit develops, the dopamine release often shifts to earlier in the habit loop – occurring when the cue appears rather than after the reward. This indicates the brain has learned to anticipate the reward. That anticipation (in essence, the “craving”) then drives the routine behavior even more powerfully. In other words, our brains begin to expect the pleasure or benefit and prompt us to act as soon as the cue is noticed.

It’s fascinating that the same brain system that helps us learn new habits also stores old ones. For a long time, scientists believed once a habit was deeply learned, it was mainly the dorsolateral striatum at work, and learning new behaviors was a separate process. New evidence suggests that these processes overlap. For instance, a 2021 neuroscience study found that the dorsolateral striatum (habit center) is also involved in learning new goal-directed actions – the very actions that can eventually become habits. This hints that the brain’s habit machinery is engaged earlier than we thought, helping lay the groundwork for future habits even during initial learning.

The downside of the brain delegating tasks to habit circuits is that habits are hard to break. Once the neural pathway is well-trodden, it doesn’t just disappear. Even if we consciously decide to stop a habit, under stress or when we’re distracted, the brain can easily fall back on its default routine stored in the basal ganglia. That’s why someone trying to quit smoking might suddenly relapse during a high-stress moment – the context triggers an old, well-worn neural routine. In fact, one study showed that when people are cognitively drained or stressed, they actually perform their habits (good or bad) more often, because the brain prefers the efficient automatic route when willpower is low. Understanding the brain basis of habits underscores an important point: willpower alone often struggles against ingrained neural loops. To change a habit, we often have to change the cues, the routine, or the reward (or all three) in a way that re-trains the brain – in essence we have to build a new habit to override the old.

Habit Triggers: Cues That Make or Break Habits

Every habit starts with a trigger. These triggers, or cues, are the drivers of our automatic behaviors. They tell our brain “do the thing now.” Understanding your habit triggers can give you tremendous insight into why you do what you do (and how to change it). What counts as a cue? It can be almost anything, but common categories include:

- Time – a specific time of day or a passing of time. (E.g., 3:00pm hits, and you instinctively reach for a snack. Bedtime routine kicks in as the clock strikes 10:00.)

- Location/Environment – where you are or your surroundings. (E.g., Walking into your kitchen might cue the habit of opening the fridge. Stepping into the gym might immediately put you in “workout mode.” Being in a movie theater cued people to eat popcorn, as mentioned, regardless of hunger.

- Preceding Event – one action that habitually leads to another. (E.g., You finish dinner and automatically start cleaning the dishes. Or you hear your phone buzz and you instantly check it. In a study, people had more success flossing when they cued it after an existing habit – finishing brushing teeth – because the prior action served as a reliable trigger.

- Emotional State – an internal feeling that triggers a routine. (E.g., Feeling bored triggers mindless web browsing or snacking; feeling stressed triggers a smoking habit or biting your nails; feeling lonely triggers calling a friend or scrolling social media for connection.)

- Other People – social cues or the presence of certain individuals. (E.g., You might have a habit of gossiping when you’re with a particular friend, or you habitually talk loudly when around a loud coworker. Being with certain people can cue drinking habits, if that’s the established routine with them.)

Crucially, a cue and action become linked in your brain through repeated pairing. Often, we aren’t even aware of the trigger at the moment – we just find ourselves doing the habit. By reflecting on when and where your habits happen, you can usually pinpoint the triggers. For instance, you might realize “I only crave a sugary snack when I’m watching TV at night,” or “I check my phone habitually when I’m feeling anxious about work.” Those are the cue moments to be aware of.

Why do triggers matter so much? Because if the trigger is removed or changed, the habit often won’t fire. Our habit system is very context-dependent. A great example of leveraging this is known as the “new context effect” – people often find it easier to change habits when they move to a new environment (new job, new city, etc.) because many of their old cues are gone. With the old triggers disrupted, it’s like the slate is cleaner to build new routines. Conversely, if you keep all your usual cues (same home, same route, same friends) while trying to change a behavior, it can be harder because everything around you is silently nudging you to stick to the old habit.

Triggers can also be used for good. When forming a positive new habit, you want to design a consistent cue that will remind you to do it. Psychologists call this implementation intentions or cue-based planning – basically, you plan “Whenever X happens (cue), I will do Y (new habit).” For example, if you decide “After I pour my morning coffee (cue), I’ll meditate for 5 minutes (new habit),” you’re leveraging an existing routine as a trigger for a new beneficial behavior. Over time, the morning coffee aroma might automatically put you in a mindful mood ready to meditate, because you’ve linked the two. Studies have found that such cue-based plans (also known as habit stacking) significantly help in forming habits because they piggyback on an already stable context.

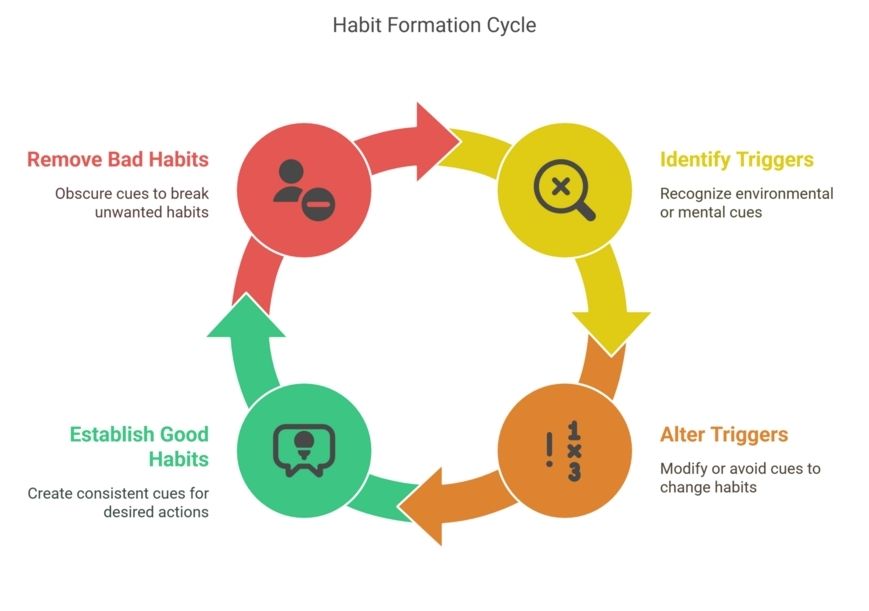

A key takeaway then, is that habits don’t arise in a vacuum – they’re tightly tied to triggers in our environment or mind. Recognizing those triggers empowers you to interrupt bad habits (by altering or avoiding cues) and to establish good ones (by deliberately choosing consistent cues and pairing them with the desired action). The mantra here is “make the cue obvious” for habits you want, and “remove or obscure the cue” for habits you want to quit.

Becoming Habit-Forming: Tips for Cultivating Good Habits

Is there a way to become the kind of person who can form new habits more easily? Psychology and behavioral science say yes. Building good habits often comes down to strategy rather than willpower. Here are some evidence-based tips for making positive behaviors stick:

Start with Tiny Steps: When attempting a new habit, make it as easy as possible to start. Research suggests that small, manageable routines are more likely to become lasting habits than grand, difficult tasks. If you want to start exercising, for example, begin with a 5-minute walk each day instead of a 30-minute gym blitz. Consistency is more important than intensity at first. By keeping the bar low, you ensure that you can repeat the action daily (consistency wires the habit) without burning out. Success with small wins also builds confidence and momentum to expand the habit later.

Use Cue-Based Planning: As discussed, tie your new habit to a specific cue so you don’t rely on “remembering” or motivation in the moment. Set an if-then plan: “If it is [situational cue], then I will [habit action].” For example: “If it’s lunchtime, I will take a 10-minute walk,” or “When I finish brushing my teeth at night, I will floss.” By anchoring the behavior to a cue or existing routine, you create a built-in reminder. Over time, the cue will automatically trigger the urge to do the new behavior, which is exactly what you want.

Make It Rewarding (and Enjoyable): A new habit won’t stick if it feels like pure drudgery. Our brains need some satisfaction to latch onto a behavior. So, find ways to make your habit immediately rewarding. This could mean pairing the habit with something you enjoy – like listening to your favorite podcast only when you’re jogging (so the run itself becomes more rewarding), or giving yourself a small treat after a study session. Some people use habit tracking charts or apps as a form of reward – e.g., the small satisfaction of checking off a completed habit each day can reinforce the behavior. The key is immediate positive feedback. If the inherent result of the habit is delayed or intangible (like health benefits that come much later), create a more instant reward in the meantime (like a healthy smoothie you love right after the workout). Consistent rewards tell your brain “this is worth doing!”

Reduce Friction: Make good habits easier to do and bad habits harder to do. This concept, sometimes called “choice architecture,” is about designing your environment and routines to favor the desired behavior. For example, if you want to practice guitar nightly, keep the guitar on a stand in the middle of your living room – visible and ready to pick up (lowering the activation energy to start playing). Conversely, if you’re trying to cut down on junk food, don’t stock the pantry with cookies, or put them on a high shelf that’s inconvenient – little obstacles (friction) can make you less likely to perform the habit. Research has shown that our default behaviors often follow the path of least resistance, so make the “good” habit the easy path.

Identity Matters: One powerful strategy is to approach habit change from an identity perspective. Instead of thinking “I want to run a marathon” (outcome-based), think “I am a runner” (identity-based). When you start viewing the habit as part of who you are, you’re more likely to stick with behaviors that align with that identity. Each small win (each run you complete) is evidence reinforcing your new self-image. Over time, your brain embraces “I’m the kind of person who exercises,” which makes skipping runs feel out of character. This strategy, advocated by many behavior change experts, essentially uses our natural desire for self-consistency as leverage. It turns a habit from just an action you’re forcing yourself to do into an expression of your values or identity. So ask yourself: “Who is the type of person that would have the habits I want?” and start embodying that in small ways. For example, a person who is a “reader” might always carry a book – so you begin carrying a book and reading a page in spare moments, claiming that identity even in tiny doses.

Be Patient and Persistent: There’s no way around it – forming habits takes time and repetition. Some days you’ll feel like it, some days you won’t. In the early phase, consistency trumps perfection. If you miss a day, just restart the next day. It’s also normal for new habits to feel unnatural or hard – that doesn’t mean you’re failing, it means you haven’t built the neural pathway strong enough yet. Keep reinforcing it. Many habit-building programs suggest a mindset of “never miss twice,” meaning if you do miss doing your habit one day, make sure you get back on track the following day. Life will interrupt, but what matters is your overall pattern.

By applying these tips, you will train your brain and environment to support your goals. Over time, your new behaviors will require less willpower and become more second-nature. In short, you’re becoming “habit-forming” – someone skilled at turning intentions into ingrained routines.

Breaking the Habit Cycle: How to Change or Stop Unwanted Habits

If habits are so ingrained, how do we break the ones that aren’t serving us? The good news is that habits can be changed, though it requires a strategic approach (and patience) to retrain your brain. Here are several science-backed steps to disrupt the habit loop and build healthier behaviors in its place:

Identify the Cue and Reward: Start by analyzing the habit you want to break in terms of the habit loop. What seems to trigger the behavior, and what reward are you getting from it? Often, just being aware of this loop can loosen a habit’s grip, because it forces your conscious brain to recognize the pattern. For instance, you might realize “I only smoke when I’m with those friends at the bar, because it helps me feel included,” or “I procrastinate on work because I get a quick rush of relief when I put it off.” Identifying the cue→routine→reward components of your habit shines a light on what your brain is really seeking. Sometimes you’ll discover that the reward isn’t something you truly value anymore, which can motivate change.

Disrupt the Routine – Remove or Replace It: To break a habit, you typically need to interrupt the habitual routine when the cue happens. One powerful method is habit substitution: replace the unwanted behavior with a different behavior that fulfills a similar need. For example, if stress at work (cue) makes you reach for a candy bar (routine) to get a sugar comfort (reward), you could try substituting with a brief walk or some stretches when stress hits, to get stress relief in a healthier way. The new behavior should ideally provide a comparable reward – perhaps the walk gives a calming endorphin effect. Over time, this can forge a new habit loop (stress -> walk -> relief). In some cases, simply removing the opportunity for the old routine is effective: if you always snack late at night because there are chips in the pantry, stop buying chips so the routine can’t occur. Adding friction to the bad habit (like keeping junk food out of the house, or putting your phone in another room to curb mindless scrolling) can significantly reduce how often you do it. The mantra here is “make it hard to do the wrong thing, and easy to do the right thing.”

Break the Cue Association: If possible, avoid or alter the cues that trigger your bad habit. Since habits are so context-dependent, changing your context can “derail” the automatic cycle. For example, if you tend to overeat while watching TV, consider separating eating from TV time – e.g. only allow yourself to watch TV after a meal, not during. If a certain route home tempts you to stop at a fast-food joint, try a different route. In cases where you can’t eliminate the cue, you can add a “speed bump” right after the cue to force awareness (for instance, if notifications make you compulsively check your phone, turn off non-essential notifications – no ping, no urge; or set a rule you’ll take one deep breath when you feel the phone itch, creating a small pause before you respond). Disrupting the cue->action connection even briefly gives your conscious brain a chance to intervene with a better decision.

Use Mindfulness and Awareness: A lot of habits happen on autopilot, so shining a light of awareness on them can weaken their power. Mindfulness practices – basically, learning to observe your thoughts, feelings, and urges without immediately reacting – can help you catch yourself in the act or before it. For instance, instead of unconsciously biting your nails, you train yourself to notice the urge to bite as it arises. In that small moment of awareness, you can choose to do something different (clench your fist, play with a pen, etc.). Studies show that simply being mindful of an urge (“oh, I’m craving a cigarette right now and my anxiety is rising”) can, over time, reduce the frequency of succumbing to it, because you’re not operating solely on autopilot. Journaling your habits or tracking them can also boost awareness. If you write down every time you indulge in the habit – noting what you were feeling or doing – you may spot patterns and become more conscious of how, say, every 2pm you wander to the vending machine out of boredom.

Try Habit Reversal Training (for stubborn habits): Habit Reversal Training is a therapeutic approach that has been very effective for certain nervous habits or tic-like behaviors (nail biting, hair pulling, tics, etc.). It consists of a few steps: (1) Heightening awareness of when the habit happens and what it feels like right before (the urge). (2) Replacing the habit with an incompatible action – a “competing response.” For example, if the habit is nail-biting, a competing response might be clenching your fists or twiddling your thumbs whenever you feel the urge to bite. (You can’t bite your nails if your hands are doing this other motion.) (3) Relaxation techniques to manage the stress or tension that often underlies these habits. (4) Support and reinforcement for using the new response. Over time, the goal is that the new response replaces the old habit in those situations. Even if your habit isn’t in this category, you can borrow the idea: identify a specific alternate behavior to do every single time the urge for the bad habit hits. Make sure it’s incompatible with the old habit and possibly even enjoyable, so it effectively substitutes the old behavior.

Reframe Your Identity and Self-Talk: Just as adopting an identity can help build habits, it can also help break them. If you’ve long thought of yourself as “a smoker” or “a junk-food lover,” that identity can subconsciously fuel the habit (“one more won’t hurt – it’s just who I am”). Try to reframe how you see yourself. For instance, start saying “I’m not a smoker” rather than “I’m trying to quit smoking.” This simple linguistic shift asserts a new identity. When faced with a cigarette, a person who “is not a smoker” will naturally refuse – that’s not what they do. It might feel like mere words, but studies have shown such framing can strengthen resolve. Similarly, avoid defeatist self-talk like “I have no willpower” – it’s more helpful to tell yourself breaking this habit is hard, but I’m getting stronger and more in control. Basically, believe you can change, and don’t define yourself by the habit you’re trying to quit. Each time you resist the old habit loop and make a better choice, mentally credit yourself for being the kind of person who can overcome habits.

Change One Habit at a Time: Finally, be careful not to overload yourself. It can be tempting to overhaul all your bad habits in one go, but that often backfires because of mental fatigue. Behavior change is doable, but it’s usually most successful when you focus on one key habit (or a small number) at a time. Once you make progress on that, you’ll also gain confidence and skills to tackle the next. This concept is sometimes called “keystone habits” – changing certain core routines (like exercise, healthy eating, or maintaining a daily schedule) can have ripple effects that indirectly improve other habits. Start with something impactful but manageable, and remember that every small victory against a bad habit strengthens your “change muscle” for future challenges.

Final Thoughts

At its core, breaking a habit is about forming a new habit (of not doing the old behavior). You’re teaching your brain a new pattern: when the old cue pops up, do something different, and ideally get a positive result from it. It takes practice, and relapses can happen – if you slip, don’t see it as failure, but as a learning experience. Analyze what triggered you and how you might handle it next time, and then get back on track. Over time, the new healthier patterns will take hold, and the old habit will gradually lose its grip. Your brain is plastic – it can always learn and re-learn, as long as you keep at it.

Know someone who would be interested in reading

How Do We Form Habits? Psychology Behind Our Daily Behaviors.

Share This Page With Them.

Go From "

How Do We Form Habits? Psychology Behind Our Daily Behaviors" Back To The Home Page