Work Burnout: What It Really Is, What Causes It, and How to Prevent It

David Webb (Founder and Editor of All-About-Psychology.com)

Having finished university and an internship, my eldest son has just secured his first job with a large multinational organization. I’m beyond proud, but I also worry (I’m his dad, that’s my job) about the impact a career path can have on a person’s wellbeing.

With both my sons, I’ve always tried to make the case that working hard and deferring gratification is a good way to ensure that great opportunities will present themselves, and when they do, they should be seized. But I’ve also been clear that I would always prefer they did a job they loved rather than one they didn’t, even if it paid significantly more.

It was against this backdrop that I wanted to write an article about life–work balance, and in particular, the dangers of burnout. So I was rather taken aback when I saw the following clip of business and leadership expert Natalie Dawson being interviewed by Steven Bartlett on The Diary of a CEO podcast, in which she put forward the view that a human being cannot burn out.

I’m conscious that this is just a short clip from a two-hour interview, and soundbites (especially controversial ones) can easily be taken out of context. So I’d encourage you to watch the full interview here. The segment on whether people really burn out starts around the 40-minute mark.

So, just to be clear, this isn’t an article aimed at Natalie Dawson. I’m simply taking her position on burnout as an entry point for assessing whether burnout is real. Interestingly, Steven Bartlett has also explored the concept of burnout with other guests, most notably with Mo Gawdat in the episode “80% of Illness Is Linked to One Thing! An Alarming Warning for the Burnout Generation” and with Dan Murray-Serter in “Overcoming Depression, Burnout, Anxiety, and Insomnia.”

So what does the science say?

What We Mean by Burnout

Burnout is one of those words that gets used so often it risks losing its meaning. It can describe anything from feeling tired after a long week to being so depleted that getting out of bed feels impossible. But in psychology and occupational health, burnout has a specific definition, and it has been studied for decades.

The term was first used in the early 1970s by psychologist Herbert Freudenberger, who noticed that many of his colleagues working in free clinics were becoming exhausted, detached, and disillusioned. They were people who cared deeply about helping others but were drained by the constant emotional demands of their work. Freudenberger called this state “burnout,” describing it as the result of excessive stress among people with high ideals.

A few years later, social psychologist Christina Maslach and her colleague Susan Jackson developed the framework that still defines burnout today. Their research identified three key components: emotional exhaustion, cynicism (sometimes called depersonalization), and a reduced sense of personal accomplishment. In other words, burnout is not just feeling tired. It is a chronic state of physical and emotional depletion, combined with growing detachment from one’s work and a loss of confidence in one’s ability to make a meaningful contribution.

This model became the foundation of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), the first standardized tool used to measure burnout. It helped establish burnout as a legitimate psychological construct rather than a vague complaint about overwork. Subsequent research has confirmed that emotional exhaustion is usually the core symptom—the point at which sustained stress turns into something deeper and more erosive.

In 2019, the World Health Organization recognized burnout as an occupational phenomenon in its International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), which came into effect in 2022. The WHO describes burnout as a syndrome resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed. Its definition mirrors Maslach’s three dimensions: exhaustion, mental distance or cynicism toward one’s job, and reduced professional efficacy.

Crucially, the WHO does not classify burnout as a medical condition but as a work-related syndrome. That distinction matters. It means burnout is not a personal failure or a psychiatric disorder, but a signal that the demands of a job have chronically exceeded a person’s resources to cope.

The Science of Exhaustion and Cynicism

To understand burnout, it helps to start with what it is not. Stress, for example, is a normal and often useful response. It mobilizes energy, sharpens focus, and helps us meet short-term challenges. When the pressure eases, the body’s stress response quiets, and balance is restored.

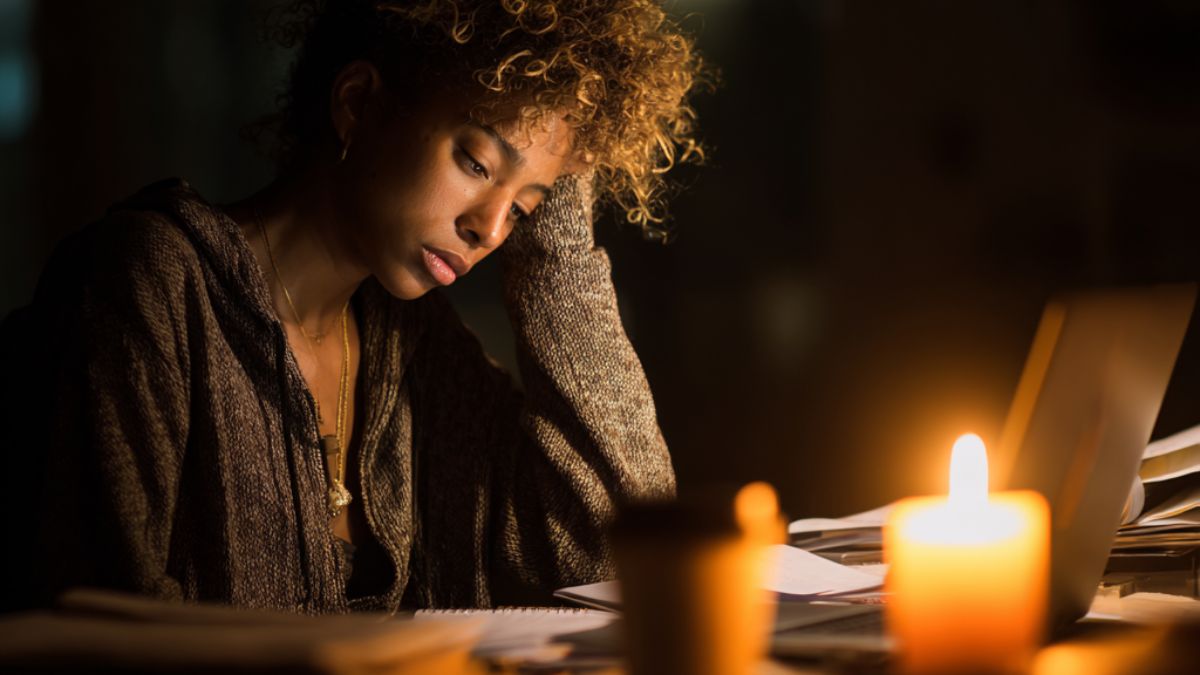

Burnout, by contrast, occurs when that recovery never happens. The stress becomes chronic, the system stays activated, and over time the body and mind begin to wear down. What begins as drive or ambition slowly turns into depletion, frustration, and finally detachment.

Researchers in the field, typically describe burnout as a gradual process that follows a predictable path. It often starts with over-engagement, when a person works harder and harder to meet demands. As the workload or emotional strain continues, energy reserves fall. The person feels physically and mentally exhausted, yet they keep pushing through. Over time, this effort gives way to cynicism or emotional withdrawal. The work that once felt meaningful begins to feel pointless or overwhelming. Finally, a sense of ineffectiveness sets in, namely, the belief that no matter how hard one tries, nothing improves.

This combination of exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy makes burnout distinct from both ordinary stress and clinical depression. Stress involves high activation, while burnout involves depletion. Depression, on the other hand, is pervasive and affects all areas of life, not just your work. Someone with burnout may still find pleasure or motivation outside of their job, whereas depression tends to color every aspect of experience.

Physiologically, burnout reflects a system stuck in overdrive. Chronic stress keeps the body’s stress hormones, such as cortisol, elevated for long periods. This prolonged activation can disrupt sleep, impair immune function, and increase the risk of heart disease and metabolic problems. On a cognitive level, it affects concentration, memory, and decision-making, which can make even simple tasks feel overwhelming.

In psychological terms, burnout represents a loss of hope and agency. Stress says, “I have too much to do.” Burnout says, “It no longer matters.” It marks a shift from effortful coping to emotional withdrawal, a defense against the sense that your energy and meaning have been drained away.

Why Some Still Question It

Even with decades of research and global recognition, not everyone agrees on what burnout really is. Some question whether it should be considered a distinct psychological syndrome at all. Others argue that it overlaps so much with depression, chronic stress, or even disillusionment that it might simply be a variation of these states rather than something unique.

Part of the confusion comes from how burnout developed as a concept. When Herbert Freudenberger and Christina Maslach first described it in the 1970s and 1980s, the idea was based largely on observation and interviews rather than controlled experiments. Over time, the three-part model exhaustion, cynicism, and reduced efficacy became the accepted standard, but not all studies have found that these three components always appear together. Some people experience severe exhaustion without detachment, while others feel cynical long before they become depleted.

This raises a question that researchers still debate today: is burnout a single, cohesive syndrome or a collection of related symptoms that often occur together? The answer matters because it affects how we measure and treat it. If burnout is not a unified condition, relying solely on one assessment tool, such as the Maslach Burnout Inventory, might overlook important variations in how people experience chronic work-related distress.

Another point of contention is the cause. The World Health Organization classifies burnout as an occupational phenomenon, which means it is directly linked to work-related stress. But it has been argued that it can also stem from emotional strain outside of work, such as caregiving or chronic financial stress. It’s also been suggested that personal factors like perfectionism, personality traits, and coping style can play a major role.

These debates are healthy for science because they refine how we think about the problem. What is not in dispute, however, is that the experience of prolonged exhaustion and detachment is both real and harmful. Brain imaging and physiological studies show clear differences in how people experiencing burnout respond to stress. They often display increased activity in brain regions associated with threat detection and emotional regulation, as well as altered cortisol patterns that reflect chronic strain.

So, while experts may debate the precise boundaries of burnout, the evidence overwhelmingly supports that it represents a genuine, measurable form of psychological and physical depletion. Where opinion differs is not on whether people suffer from it, but on exactly how to define and address it.

The Systemic Nature of Burnout

If burnout were only a matter of personal weakness or poor coping, the solution would be simple: rest more, toughen up, or find better balance. But research shows that burnout is rarely caused by individual failings. It is most often a response to chronic structural strain within organizations and work cultures.

The Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model, developed by psychologist Wilmar Schaufeli and colleagues, provides one of the clearest explanations of how burnout develops. According to this model, every job contains two essential elements: demands and resources.

Job demands are the physical, emotional, or cognitive efforts required to perform a role. These include heavy workloads, time pressure, emotional labor, and conflicting expectations. High demands are not inherently negative, but when they are excessive or constant, they begin to drain a person’s energy faster than it can be replenished.

Job resources, on the other hand, are the aspects of work that help people meet those demands, grow, and stay motivated. Resources can include autonomy, fair treatment, recognition, clear communication, and supportive relationships. When resources are abundant, they protect against exhaustion and promote engagement. When they are scarce, even moderate demands can feel overwhelming.

The JD-R model identifies two interlinked processes. The first is the health impairment process, where high demands without sufficient recovery lead to exhaustion. The second is the motivational process, where a lack of resources erodes enthusiasm and meaning, leading to cynicism and reduced professional efficacy.

This model reframes burnout as a predictable outcome of imbalance, not a sign of individual fragility. A person can be highly resilient, motivated, and capable, but if their work continuously depletes energy without replenishment, burnout becomes a matter of time. The body and mind are not designed for sustained strain without recovery.

Organizational studies have consistently identified several systemic risk factors. Among the strongest are unfair treatment, unmanageable workloads, unclear roles, poor communication, and chronic time pressure. These factors are not only stressful but also signal to employees that their efforts are undervalued or unsupported, accelerating disengagement.

Leadership quality plays a critical role in either worsening or preventing burnout. Managers who provide regular feedback, clear expectations, and social support help buffer the effects of high demands. Conversely, inconsistent or unsupportive leadership amplifies stress and leaves employees feeling isolated.

In short, burnout is less about individual endurance and more about the ecosystem people work in. The JD-R model shows that prevention must happen at both levels: reducing unreasonable demands while actively building the resources that sustain motivation and meaning.

The Cultural Pressure to Push Through

While burnout often begins in the workplace, it does not exist in isolation. Wider culture plays a powerful role in shaping how people experience work and stress. Over the past decade or so, what has come to be called hustle culture has redefined exhaustion as a sign of ambition and blurred the boundaries between professional success and personal worth.

In many fields, long hours, constant availability, and relentless productivity are worn like badges of honor. Social media reinforces the message that high achievers never rest. Sleep, leisure, and even reflection are framed as indulgences rather than necessities. The problem is that this mindset treats human energy as an unlimited resource when biology tells us otherwise.

Essentially this is a cycle of compulsive overcommitment. At first, working harder produces results and recognition, which reinforces the behavior. Over time, however, the demands keep increasing while recovery time shrinks. The individual’s sense of self becomes tied to output, so stepping back feels like failure. The eventual result is emotional and physical depletion.

This cultural glorification of overwork also makes it harder to recognize the early warning signs of burnout. People may tell themselves they are simply “pushing through a tough patch” or that “everyone feels this way.” In reality, the boundary between motivation and exhaustion is far thinner than most realize.

The digital era has made matters worse. Remote work, smartphones, and constant connectivity have erased the natural stopping points that once separated work from rest. For many, emails and notifications fill every quiet moment, turning downtime into an extension of the workday. The psychological effect is cumulative. Without deliberate boundaries, the body and mind never fully disengage, and recovery becomes incomplete.

Cultural expectations also interact with personality traits. People who are conscientious, empathetic, or driven by high ideals are often at greater risk because they struggle to say no. They are also more likely to interpret exhaustion as a personal weakness rather than a systemic issue.

Reclaiming balance, then, is not just an individual challenge but a collective one. Cultures that celebrate rest, reflection, and sustainable productivity are far less likely to produce widespread burnout. Those that reward overextension will continue to see exhaustion as the price of success.

Rethinking Recovery and Prevention

Understanding burnout as both a psychological and systemic phenomenon means that recovery must happen on two levels. Individuals can take steps to restore balance, but lasting change depends on organizations addressing the structural causes that make burnout inevitable.

At the individual level, research highlights several approaches that help rebuild energy and perspective. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has shown consistent success in treating burnout-related symptoms, especially when exhaustion is accompanied by feelings of hopelessness or self-blame. CBT helps people identify unhelpful thought patterns such as “I can’t stop or everything will fall apart,” and replace them with healthier, more realistic beliefs. It also strengthens psychological flexibility, the capacity to adapt one’s mindset when facing chronic pressure.

Mindfulness and relaxation-based techniques can also reduce emotional exhaustion. Practices such as meditation, yoga, and controlled breathing lower physiological arousal and restore a sense of calm. Unlike passive rest, mindfulness helps people become more aware of their internal state and recognize early signs of depletion before they escalate.

Another evidence-based approach is job crafting, which involves reshaping your role to increase meaning and control. Rather than waiting for management to redesign the job, employees can take small, proactive steps such as seeking feedback, requesting varied tasks, or collaborating more closely with supportive colleagues. Studies show that this sense of agency improves motivation and buffers against feelings of ineffectiveness.

However, no amount of personal effort can offset the effects of a chronically unhealthy workplace. The science is clear that the most powerful predictors of burnout are structural: unfair treatment, excessive workload, unclear roles, and poor managerial support. This means the responsibility for prevention lies as much with organizations as with individuals.

Leaders and managers play a particularly vital role. Supportive leadership, characterized by clear communication, recognition, and fairness, consistently predicts lower burnout rates. When employees feel heard and valued, their capacity to handle pressure improves dramatically. In contrast, environments that ignore feedback or reward overextension quickly erode morale and motivation.

Building a sustainable culture requires deliberate design. Policies that protect non-work time, encourage regular breaks, and promote realistic workloads are not luxuries, they are essential components of long-term productivity. Encouraging open conversations about mental health and training managers to recognize early warning signs can also prevent minor stress from turning into chronic burnout.

Ultimately, recovery is not only about reducing strain but about restoring meaning. People thrive when they feel their work matters, when effort leads to progress, and when they have space to rest without guilt. The most resilient organizations are those that understand this balance and see well-being not as a perk, but as the foundation of effective performance.

Final Thoughts

The claim that a human being cannot burn out may sound bold, but the science tells a different story. Burnout is real, measurable, and deeply human. It reflects the point at which the demands placed on a person chronically exceed their ability to recover. The result is not just tiredness but a loss of energy, meaning, and connection to purpose.

That does not make it a sign of weakness. It makes it a warning signal. Burnout is not a failure of character but a failure of balance, one that can affect anyone who cares deeply about their work and keeps giving more than they can sustainably give.

For individuals, recovery often begins with awareness. Paying attention to early signs of exhaustion, irritability, or detachment allows for small adjustments before the system breaks down. Taking rest seriously, setting clear boundaries, and seeking support are not indulgences. They are forms of maintenance that make long-term engagement possible.

For organizations, prevention means moving beyond wellness slogans and addressing root causes. Fairness, clear communication, realistic workloads, and genuine respect for personal time are not optional. They are the foundations of a healthy culture. When these are in place, people feel safe to contribute, take risks, and grow without fear of collapse.

Culturally, we need to rethink what success looks like. If constant exhaustion has become the norm, perhaps the system is the problem, not the people in it. The evidence from psychology, medicine, and organizational science all points in the same direction: human beings are not built for endless output. They are built for rhythm, recovery, and connection.

As I watch my sons begin their careers, I hope they find fulfillment and challenge in equal measure. I hope their ambition is matched by rest, and their hard work by meaning. Most of all, I hope the world of work they enter recognizes that thriving and burning out are not opposites on a single scale but entirely different systems, one sustainable, the other self-destructive.

I began this article with a Diary of a CEO podcast clip representing one side of the burnout debate, so it feels fitting to end with another clip that sits at the opposite extreme. Together, they capture the tension between ambition and exhaustion that defines so much of modern work - a reminder that how we understand burnout will shape not only how we work, but how we live.

@steven THIS 🙏🏽👏🏽 Episode OUT NOW! #stevenbartlett #thediaryofaceo #garyvee #garyveechallenge #burnout ♬ original sound - The Diary Of A CEO

🚀 Want to get your brand, book, course, newsletter, podcast or website in front of a highly engaged psychology audience? I can help!

All-About-Psychology.com now offers advertising, sponsorship and content marketing opportunities across one of the web’s most trusted psychology platforms - visited over 1.2 million times a year and followed by over 1 million social media followers.

Whether you're a blogger, author, educator, startup, or organization in the psychology, mental health, or self-help space - this is your chance to leverage the massive reach of the All About Psychology website and social media channels.

🎯 Exclusive placement

🔗 High-authority backlink

👀 A loyal niche audience

Learn more and explore advertising and sponsorship options here: 👉 www.all-about-psychology.com/psychology-advertising.html