The Psychology of Smiling: Why We Smile and What It Communicates

David Webb (Founder and Editor of All-About-Psychology.com)

One thing I’ve always loved about psychology is its ability to make sense of everyday behavior. Smiling is a great example. Like many things in our behavioral repertoire, we take it for granted. It’s something we do without much thought, which is probably why so few of us ever stop to ask why we smile in the first place. Psychology does, and its answers are fascinating.

My personal interest in this topic began years ago when I came across a classic study that tested two competing theories about the psychology of smiling. The first theory suggests that smiling is primarily an individual act. We smile because we feel good on the inside. The second theory treats smiling as mostly a social act. We smile to show other people that we feel good. Two different explanations for the same common human expression.

To test these theories, Robert Kraut and Robert Johnston at Cornell University did something wonderfully simple. They went bowling. They chose this setting for the ingenious reason that the moment someone bowls a strike, it offers a rare window into the individual versus social smile. When the ball hits the pins, the bowler is facing away from everyone else. That moment of happiness is private. Seconds later, the bowler turns toward teammates, family, or friends, and now the joy becomes public.

The results were clear. Only 4 percent of bowlers smiled while still facing the pins after a strike or spare. Once they turned around, the number jumped to 42 percent. It was strong evidence that smiling is shaped far more by social context than by inner feeling alone.

Commenting on the study, the late great psychologist Ed Diener wrote:

The smile is a facial response that is recognized around the globe and helps bind people together. We are indeed a “social animal.” and the smile is a central way we communicate. I once did a study that blew up in my face because I asked a group of participants not to smile for three days and they absolutely could not do it. I had a rebellion on my hands because the smile is so crucial to effective social interactions.

The bowling study was my way into the topic, and it opened the door to a much larger story on the subject. This article is an attempt to explore that story, because once you start looking at smiling through a psychological lens, you discover that it’s far more complex than a simple friendly gesture. Smiling has an intricate anatomical basis, a surprising evolutionary history, powerful effects on our physiology, and a wide range of social functions that go well beyond a basic expression of happiness.

The Anatomy of a Smile

Before we get to the deeper story of why we smile, it helps to understand what a smile actually is at the level of facial movement. Psychologists and anatomists have spent decades studying the mechanics of expression, and smiling turns out to be far more precise than most people imagine. What looks like a simple lift of the mouth is built from a coordinated pattern of muscle activations that the brain manages with remarkable efficiency.

The standard tool for describing these movements is the Facial Action Coding System, known as FACS. Instead of relying on subjective interpretations like “happy” or “friendly,” FACS breaks every facial expression into measurable units of movement called Action Units. Each unit corresponds to a specific muscle or muscle group, which allows researchers to describe expressions with anatomical accuracy.

The basic smile is driven by one muscle in particular. When the Zygomaticus Major contracts, it pulls the corners of the mouth upward and outward. In FACS terms this is Action Unit 12. It is the movement most people imagine when they picture a smile, and it appears in both polite and genuine forms of the expression. On its own, though, this movement tells only part of the story.

The richer and more psychologically meaningful version of the smile is called the Duchenne smile, named after the French neurologist Guillaume Duchenne, who first described this genuine expression in the 1860s. In addition to the upward pull at the mouth, it includes the activation of the Orbicularis Oculi, which raises the cheeks and produces the characteristic softening and crinkling around the eyes. In FACS, this is Action Unit 6. It is significantly harder to produce voluntarily, and this difficulty is precisely why its presence signals authenticity. The muscle is controlled in part by pathways that respond to genuine emotional states, rather than conscious intention.

This anatomical difference matters because people are remarkably good at detecting it, often without realizing they are doing so. When both muscles are active, the smile is usually judged as warmer, more trustworthy, and more sincere. When only the mouth moves, the smile tends to feel polite or controlled. Neither type is inherently better or worse. They simply serve different roles. But the tiny shift created by Action Unit 6 carries meaning that our brains read with surprising speed and accuracy.

Understanding the anatomy of a smile gives us a foundation for everything that follows. It helps explain how smiles function in social settings, why some feel genuine and others feel forced, and how the face can communicate layers of meaning long before words enter the conversation. It also sets the stage for the evolutionary story, because the movements that shape our modern smile did not emerge by accident. They have deep roots in the history of our species.

The Evolutionary Story

Once you understand the anatomy of a smile, the next natural question is where this expression came from in the first place. Today we think of smiling as a sign of happiness, friendliness, or openness, but its origins are far older and far more complicated. The modern human smile did not begin as a symbol of joy. Its earliest roots lie in the social lives of primates, where baring the teeth had a very different purpose.

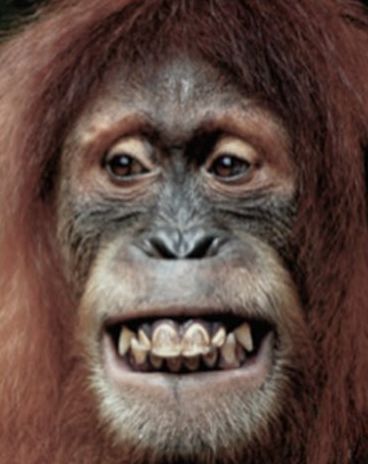

One of the most widely accepted explanations links the smile to the “silent bared teeth display” seen in monkeys and apes. In these primate groups, the expression appears in situations involving social tension, hierarchy, or potential conflict. Rather than signaling happiness, it signals submission. The animal pulls back the lips to show the teeth in a quiet, nonaggressive way that communicates, in effect, “I am not a threat.” The gesture helps prevent aggression from higher-status individuals and smooths interactions within the group.

Silent bared-teeth display in an orangutan, an evolutionary precursor to the human smile. Photo by Dr. Katja Liebal (CC BY 4.0).

Silent bared-teeth display in an orangutan, an evolutionary precursor to the human smile. Photo by Dr. Katja Liebal (CC BY 4.0).A related idea, known as the defensive mimic theory, traces the origins of the smile even further back. According to this view, the earliest ancestor of the smile was a fast, involuntary grimace used to protect the face during an attack. Over evolutionary time, this protective reflex was exaggerated, slowed down, and adapted into a social signal that could reduce tension and prevent conflict. In other words, what eventually became a friendly human smile may have begun as a defensive reaction that was gradually repurposed.

This evolutionary background helps explain why we see smiles in situations that have nothing to do with joy. People often smile when they feel awkward, anxious, embarrassed, or unsure of themselves. In those moments the smile functions less as a sign of personal happiness and more as a way to regulate the social environment. It signals cooperation, appeasement, or a desire to reduce tension, much like its primate ancestor.

Despite this deep evolutionary history, there is also evidence that smiling has an innate component in humans. Research with congenitally blind children shows that they smile in contexts similar to sighted children, even though they have never observed a smile. This suggests that the basic expression is built into our biology. At the same time, the intentional, socially directed smile that we use in conversation appears to develop through experience. Children learn how, when, and why to use it by watching the people around them.

When we combine these evolutionary and developmental findings, a more complete picture emerges. The human smile is not simply a display of inner emotion. It is a flexible tool shaped by both biology and social life, capable of expressing warmth, reducing tension, and managing the delicate dynamics of group living. Understanding this deeper history helps make sense of why smiling plays such a central role in our daily interactions, and why it can carry meanings that go far beyond happiness.

Smiling From the Inside Out

After looking at how a smile is built and where it came from, the next question is what smiling does to us internally. We often think of smiling as an outward sign of emotion, but there is a steady stream of evidence showing that the expression also works in the opposite direction. The act of smiling can influence how we feel, how we cope with stress, and how our body responds to challenging situations.

One of the main theories behind this idea is the facial feedback hypothesis. The basic claim is simple. When we form an expression, the brain receives signals from the muscles in the face and uses them as part of the emotional experience. In other words, the face is not just a display system. It is part of the emotion system itself. The theory has been debated at times, but recent large-scale studies have provided strong support for the idea that facial movement can shape emotional experience, particularly when the emotion is mild or neutral to begin with.

The influence of smiling becomes even clearer in studies of stress. When people go through a stressful task, those who smile tend to recover more quickly. Their heart rate returns to baseline faster, and their overall physiological arousal is lower. This effect is especially noticeable when the smile includes the muscle around the eyes. The genuine, full expression appears to send a stronger message to the nervous system that the situation is manageable, which helps shift the body out of a heightened stress response.

Smiling can also influence how we experience pain. In experiments where participants undergo mild but uncomfortable procedures, such as receiving a needle, those encouraged to smile report less pain and show lower physiological reactivity. The expression seems to soften both the subjective and physical response to discomfort, acting as a small but reliable buffer.

What makes these findings compelling is that they do not rely on intense emotions or dramatic situations. The effects often appear in everyday contexts, where a smile is enough to tilt the experience in a slightly more positive direction. It is a reminder that our emotional lives are shaped by a mix of outward expression and inward response, and that the boundary between the two is far more fluid than we might expect.

Understanding smiling from the inside out adds another layer to its psychological significance. A smile is more than a signal to others. It is also a quiet form of self-regulation, capable of shaping the body’s response to stress and helping us manage the challenges of daily life.

The Social Functions of Smiling

By this point in the story, smiling has revealed itself as an expression with a remarkable amount of internal complexity. It has a specific anatomical signature, deep evolutionary roots, and measurable effects on how we feel inside. But most of the time, smiling unfolds in the presence of other people, which means its social function is just as important as its physiological one. In everyday life a smile is rarely a simple display of happiness. It is a social signal that helps manage relationships, coordinate behavior, and convey intent.

Researchers studying social communication often group smiles into three broad categories: reward smiles, affiliative smiles, and dominance smiles. Each category reflects a different interpersonal purpose, and each has subtle physical features that help observers interpret the intended message.

Reward smiles are the most familiar. They are the warm, encouraging expressions people use to reinforce positive behavior in others. These smiles are usually symmetrical and may be accompanied by slight eyebrow raises or softening of the upper face. When someone laughs at a friend’s joke, congratulates a colleague, or responds to a child’s excitement, reward smiles help strengthen the connection. They function as positive feedback, creating an emotional loop that encourages more of the same behavior.

Affiliative smiles serve a different purpose. Rather than reinforcing behavior, they signal friendliness, cooperation, and safety. These are the smiles we use when meeting someone new or trying to create a comfortable atmosphere. They tend to be softer and sometimes include a slight pressing of the lips. Affiliative smiles help reduce social distance and make interactions feel smoother, which is why they are so common in situations that require trust or collaboration.

Dominance smiles are more complex and less widely recognized, but they play an important role in social hierarchy. These smiles can be asymmetrical and may involve additional movements like a slight lift of the upper lip or a brief wrinkling of the nose. Rather than expressing warmth, they communicate confidence, control, or superiority. Dominance smiles help establish or maintain status within a group, often in subtle ways that others pick up on without conscious effort.

One of the most striking findings in this area is how accurately people can distinguish these smile types based solely on facial cues. Even without words, observers tend to pick up the social message embedded in the expression. This sensitivity reflects the smile’s long evolutionary history as a tool for navigating group life. The expression may have begun as a signal of submission or appeasement, but over time it became a flexible system for managing a wide range of social situations.

These social functions help explain why smiling is so common in contexts that have nothing to do with joy. When someone smiles politely in a tense meeting, or offers a quick grin to ease an awkward moment, they are drawing on the affiliative role of the smile. When a person uses a confident, controlled smile in a competitive setting, they are leaning on its dominance function. Even simple encouragement, like cheering a friend or student, reflects the reward function that helps strengthen social bonds.

Understanding these different types of smiles highlights how much social information we convey without speaking. A smile can invite cooperation, soften tension, reinforce good behavior, or assert status. It can make interactions feel safer and more predictable, which is why it plays such a central role in how groups function.

How Smiling Shapes Perception

Smiles do more than regulate social situations. They also change the way we are seen. From the outside, a smile sends an immediate signal about warmth, trust, confidence, and even personality. These judgments form quickly and often guide how people respond to us long before we speak. Because the smile has such deep evolutionary and social roots, the human brain pays close attention to it when forming first impressions.

One of the strongest and most consistent findings in social psychology is that smiling increases perceived approachability. People are more willing to initiate conversation, ask for help, or sit next to someone who is smiling. The expression signals friendliness and low threat, which encourages others to engage. This effect appears in everyday situations, from customer interactions to workplace meetings, and it plays a major role in how easily relationships begin.

Smiling also influences perceptions of trust and warmth. When people see a genuine smile, they tend to assume that the person is more honest, cooperative, and reliable. This response is not entirely conscious. The eye movement associated with a genuine smile gives observers confidence that the expression matches the person’s internal state. Even slight differences in the way the eyes and mouth move can shift how trustworthy someone appears, which shows how sensitive we are to the subtleties of the expression.

Beyond trust and approachability, smiling shapes impressions of confidence and attractiveness. In several studies, participants rated smiling faces as more attractive and more self-assured than neutral faces. This effect even influences professional settings. People who smile are sometimes judged as more competent or more successful, although this can vary with context. The expression tends to create a positive halo, where warmth and confidence are assumed to go together.

Another interesting finding involves personality perception. When people smile in photographs or during brief interactions, observers tend to make slightly more accurate judgments about their personality traits. The expression appears to reduce the tension involved in masking or suppressing emotion, allowing more authentic cues to be visible. This gives the observer a clearer, though still limited, window into traits like openness, agreeableness, or emotional stability. In this sense, the smile acts as an amplifier, making it easier for others to read who we are.

These perceptual effects highlight how powerful a single expression can be in shaping daily interactions. A smile can invite connection, build trust, and shift the way others interpret our actions. It can change the emotional tone of an encounter within seconds, even when nothing else about the situation has changed. At the same time, smiling can also be used strategically to influence perception, which brings us to an important and often overlooked part of the story: what happens when a smile hides more than it reveals.

When Smiling Hides More Than It Reveals

For all the warmth and clarity a smile can convey, it can also create confusion. People often use smiling to manage social expectations, soften uncomfortable moments, or mask feelings they would rather keep private. This strategic use of smiling is common across many cultures and often learned early in life. Families that discourage open displays of negative emotion, for example, can inadvertently teach children to smile through frustration, sadness, or discomfort. Over time the expression becomes a way of keeping difficult feelings out of sight.

The challenge with masking is that the face is not fully under voluntary control. While the smile itself can be posed, the muscles of the upper face are much harder to regulate. This means that certain signs of underlying emotion, particularly around the eyes and forehead, can still appear. Researchers refer to these mixed expressions as emotional blends. They happen when the controlled movements of a smile combine with involuntary muscle actions linked to fear, anger, or distress.

Observers are surprisingly sensitive to these blends. When a smile contains traces of fear, people tend to judge it as less happy and less authentic. The two emotional signals conflict, and the smile loses its positive meaning. A different pattern appears when the blend involves anger. In some cases, a smile with slight tension in the brows is interpreted as more genuine than expected. This happens because the added tension can align with one of the smile’s social functions, particularly the dominance smile, which blends confidence and control rather than warmth.

These subtleties show how easily a smile can be misread. A friendly expression may be hiding stress, fatigue, or social discomfort. A controlled smile may be mistaken for confidence or ease. Even a small trace of another emotion can shift how the expression is interpreted. Because smiling plays such a central role in social communication, these misreadings can shape interactions more than the person intends.

There is also a psychological cost to habitual masking. Smiling through negative feelings can help in the short term, especially in professional settings where emotional restraint is expected. But when used constantly, it can create distance between what a person feels internally and what they show externally. Over time this gap can contribute to emotional strain, reduced self-awareness, and difficulty connecting with others. The expression that usually brings people together can, in these cases, create a sense of being unseen or misunderstood.

Recognizing these limits adds an important layer to the psychology of smiling. The expression is powerful, but it is not transparent. It can reassure, encourage, and comfort, but it can also conceal, confuse, or conflict with the emotions underneath. This complexity becomes even clearer when we look at how smiling develops across childhood and how different cultures shape when and how it is used.

Development and Culture

To understand the full story of smiling, it helps to look at where the expression begins and how it changes as we grow. Smiling is one of the earliest facial movements to appear in infancy, but it does not begin as a fully social gesture. It moves through several stages before becoming the flexible, context-sensitive expression adults use in daily life.

In the first weeks of life, newborn smiles are reflexive. They appear during drowsy states, light sleep, or shifts in physiological arousal. These early smiles are not directed at people and do not carry social meaning. They are simply part of the developing nervous system. Although this has long been the standard view, newer research suggests that infants may show meaningful, socially responsive smiles earlier than once believed, particularly in moments of alert, face-to-face interaction. The evidence is still developing, but it adds a more nuanced layer to the traditional reflex-to-social progression.

By around six to eight weeks, infants begin to smile in response to pleasant sensations or stimulation, although the expression is not yet fully intentional. The social smile emerges between two and three months of age, and it marks an important milestone. At this point, infants begin to smile in recognition of familiar faces. The smile becomes part of face-to-face interaction, and caregivers respond with smiles of their own. This mutual responsiveness strengthens the early bond between parent and child and lays the foundation for later social development. By around nine months, infants begin to smile selectively, directing warmer or more sustained smiles toward preferred individuals. This shift reflects growing cognitive abilities, as children start to distinguish between familiar people and strangers.

Although these developmental milestones appear across cultures, the way smiling is used and interpreted varies widely from one society to another. Cultural display rules shape when it is appropriate to smile, how intense the expression should be, and what emotional states the smile is expected to represent.

In cultures where positive emotion is highly valued, such as the United States, smiling is common in both casual and formal contexts. People are encouraged to smile in photographs, during greetings, and even when interacting with strangers. In these settings the smile serves as a general expression of friendliness and is closely tied to ideas about approachability and optimism.

In contrast, cultures that prioritize emotional restraint may smile less frequently or reserve smiling for specific situations. In Japan, for example, smiling can signal politeness rather than happiness, and people often focus more on the eyes than the mouth when interpreting emotion. This makes sense in a context where the mouth is easily controlled for social reasons, while the eyes are considered a more reliable source of information.

Other cultures place strong value on sincerity and authenticity. In parts of Eastern Europe, particularly Poland, smiling without genuine positive feeling can be seen as insincere or inappropriate. The expectation is that outward expression should reflect inner emotion, which leads to different judgments about when smiling is acceptable.

Even in countries with high levels of well-being, such as Switzerland, smiling may serve a more formal purpose, expressing respect during conversation rather than signaling personal joy.

These cultural differences highlight an important point. Although the basic architecture of the smile is universal, its meaning is not fixed. People use and interpret the expression through the lens of their cultural values, social norms, and shared expectations. Understanding these variations helps prevent miscommunication and deepens our appreciation of how a single facial movement can carry so many different meanings across the world.

Smiling is a behavior that begins as a reflex, grows into a social tool, and then becomes shaped by the cultural environment. These layers of development and cultural influence prepare us for the final part of the story, which brings together all the threads and considers what smiling reveals about human psychology as a whole.

Final Thoughts

Smiling may seem like a simple human behavior, yet as we’ve seen, it’s anything but. What began as a quick defensive movement in our primate ancestors has become one of the most versatile tools in human social life. It is built from a small set of facial movements, yet those movements reveal more about emotion, context, and intention than most people ever realize.

The anatomy of a smile gives us our first glimpse of this complexity. A slight shift around the eyes can change how sincere an expression feels, and the brain is remarkably accurate at picking up that difference. The evolutionary background adds another layer, reminding us that smiling was not originally about happiness at all. It emerged as a way to reduce threat, signal cooperation, and keep social interactions stable.

From the inside out, smiling does more than display emotion. It feeds back into the nervous system, shaping how we experience stress and discomfort. Even a small smile can shift the body toward a calmer state. In social settings, the expression plays multiple roles. It can reward, reassure, welcome, or assert confidence. It can smooth interactions, encourage connection, and influence how others see us. A single smile can change the entire tone of an encounter.

Yet smiling also has limits. It can conceal tension, hide sadness, or offer a polite surface over more complicated feelings. Emotional blends remind us that the face is only partly under conscious control, and that even the warmest smile can carry hints of something else underneath. This mix of voluntary and involuntary movement is part of what makes the expression so psychologically rich.

Across development and culture, smiling reveals even more variety. Infants grow from reflexive smiles to intentional ones that help build relationships. Different cultures shape when and how people smile, what the expression is meant to communicate, and how observers interpret it. The meaning of a smile is never fixed. It moves with context, history, personal experience, and cultural norms.

Taken together, these layers show why smiling is one of the most studied expressions in psychology. It is biological, emotional, social, and cultural. It can express joy, soothe tension, signal cooperation, or create distance. It can reflect what we feel or mask it. It can draw people closer or help us navigate uncertainty. A smile is not only an expression of emotion. It is a flexible, adaptive behavior that sits at the heart of human connection.

🚀 Want to get your brand, book, course, newsletter, podcast or website in front of a highly engaged psychology audience? I can help!

All-About-Psychology.com now offers advertising, sponsorship and content marketing opportunities across one of the web’s most trusted psychology platforms - visited over 1.2 million times a year and followed by over 1 million social media followers.

Whether you're a blogger, author, educator, startup, or organization in the psychology, mental health, or self-help space - this is your chance to leverage the massive reach of the All About Psychology website and social media channels.

🎯 Exclusive placement

🔗 High-authority backlink

👀 A loyal niche audience

Learn more and explore advertising and sponsorship options here: 👉 www.all-about-psychology.com/psychology-advertising.html

Know someone who would be interested in reading

The Psychology of Smiling: Why We Smile and What It Communicates.

Share This Page With Them.

Go From "The Psychology of Smiling: Why We Smile and What It Communicates” Back To The Home Page