The Psychology of Friendship: How Friends Impact Health and Happiness

Introduction

Friendship in action: In the image above friends share a lighthearted moment, illustrating the comfort and joy that close companionship can bring. Friendships are a voluntary, personal bond – unlike family ties or romantic partnerships, we choose our friends and they choose us. Psychologists describe friendship as an interpersonal relationship marked by mutual affection, equal give-and-take, and an absence of formal obligations. Classic research suggests five key features define friendship: it’s voluntary, mutual, personal, affectionate, and grounded in a sense of equality. Yet defining friendship isn’t always straightforward. Cultural and individual differences can blur the lines between friend and acquaintance, and the concept has evolved with our social networks and online connections. For example, someone with a relational-interdependent self-construal – the tendency to define oneself through close relationships – may call many people “friends” and invest heavily in those bonds, whereas others draw a sharper line between casual pals and true confidants. Despite these conceptual challenges, most agree that at its core, friendship is about connection: friends are people we trust, enjoy, and turn to for support, even without any blood relation or romantic commitment.

Friendship Across the Lifespan: From Playmates to Lifelong Companions

Friendship is a dynamic relationship that evolves over the lifespan. In early childhood, friends are often just playmates – someone to share toys and imagination with. These first friendships help children develop social skills like sharing, empathy, and conflict resolution. By adolescence, friends take on a new importance as teenagers use their peer group to explore identity and independence. Teens often choose friends who reflect the identities they aspire to (“virtual mirrors”), which can sometimes encourage cliques or even deviant behavior if the group norms skew that way. Psychologists refer to “deviancy training” to describe how adolescent friends can reinforce rule-breaking or risky behavior: for instance, when peers laugh or cheer at mischief, it rewards the behavior and increases the likelihood of future delinquency. This is one reason why having positive peer influences during the teen years is so crucial.

In young adulthood (the 20s and 30s), friendship circles tend to expand and then narrow based on life transitions. Many young adults form numerous connections in college or the workplace, yet deep quality friendships may be fewer. Time becomes a limiting factor as careers start and romantic relationships or parenthood demand attention. Under these pressures, friendships that endure life changes – like a big move or a marriage – often become stronger, serving as buffers against stress. In fact, research shows that if a friendship can weather major transitions, it can help reduce the stress of those life changes.

By midlife (“truly adult” years and into one’s 40s and 50s), people often have established careers and families, and their friendship needs may shift. Many cultivate a smaller inner circle of trusted friends for genuine support and authenticity over quantity. There’s less tolerance for superficial or one-sided friendships; instead, people gravitate toward friends who offer honesty, acceptance, and mutual respect. It’s common for friendships to pause or loosen when raising children or dealing with intense work demands, then rekindle later when there’s more free time.

In older adulthood, friendship takes on renewed significance. Social circles often shrink in later life due to retirement, mobility issues, or the loss of peers through illness and death. Consequently, the friendships that remain can profoundly affect emotional well-being. According to socioemotional selectivity theory, as people age they become increasingly selective in their social relationships, prioritizing those that are most emotionally meaningful. Older adults tend to “prune” their networks, investing energy in a few close friendships that provide the most joy and support, rather than broad networks of casual contacts. This selectivity maximizes positive experiences and minimizes emotional risk in one’s remaining time. Indeed, studies find that having at least a few close friends in old age is linked to higher life satisfaction and even longevity. Conversely, lack of social contact later in life can lead to loneliness and depression– a serious public health concern given that an estimated 1 in 4 older people experience social isolation. On the bright side, it’s never too late to make new friends or deepen existing ones; even minimal social interactions (chatting with a neighbor or attending a group activity) can boost mood and sense of connection.

Gender Differences in Friendships

Psychologists have long observed that men and women, on average, navigate friendships differently. Cross-culturally, men tend to report having a larger number of friends but with somewhat less intimacy in those relationships, whereas women generally have fewer total friends but deeper, more emotionally close ties with each. Women are more likely to identify a “best friend” and to distinguish between close friends and casual friends. They often seek friendships high in emotional support, personal disclosure, and frequent contact. In fact, female friendships often thrive on intimacy and validation – talking about feelings, offering support, and spending one-on-one time together. Evolutionary psychologists have noted a “tend-and-befriend” pattern in women’s stress responses: in stressful times, women’s bodies release oxytocin (the bonding hormone) which, combined with socialization, encourages seeking comfort in friends rather than a fight-or-flight reaction. This may explain why, for example, studies found women with strong friend networks coped better and even had higher survival rates in health crises like breast cancer. Women often maintain active friendships – staying in frequent touch, remembering birthdays, scheduling coffee dates – and may feel a friendship has faded if regular contact lapses. The upside is a tight-knit support system; the potential downside is that such friendships can be emotionally intense and, at times, fragile if needs for communication and support aren’t met.

Men’s friendships, by contrast, often center on shared activities or interests rather than deep emotional exchange. It’s common for male friends to bond through playing sports, gaming, working on projects, or joking around, with less emphasis on personal disclosure. A classic observation is that two men can spend an entire afternoon together (say, watching a game or fishing) and come away feeling fully satisfied with the friendship without ever discussing personal issues or feelings in depth. One study noted that men use the term “friend” more loosely and tend to expect less emotional support from friendships than women do. Men can go long periods – weeks or months – without contact and still consider each other good friends. These “low-maintenance” friendships are often resilient; they aren’t as easily hurt by a lack of regular communication, and conflict may be shrugged off or resolved through lighthearted banter. On the other hand, male friendships sometimes lack the emotional depth that can be so protective in times of distress. Societal expectations play a role here: traditional masculine norms discourage men from being openly vulnerable or affectionate with friends, which can limit intimacy. The roots of these sex differences likely stem from both social conditioning and evolutionary history. Some evolutionary psychologists propose that, in early human groups, male alliances centered on cooperative activities (hunting, defense) with clear hierarchies, whereas female alliances centered on family and community support networks, fostering closer emotional sharing. Regardless of the origin, it’s important to remember these are averages – many men have deeply supportive friendships and many women enjoy large, activity-focused friend circles. Gender is just one factor; personality and cultural norms also shape how we approach friendship.

Friendship and Health: The Impact on Well-Being

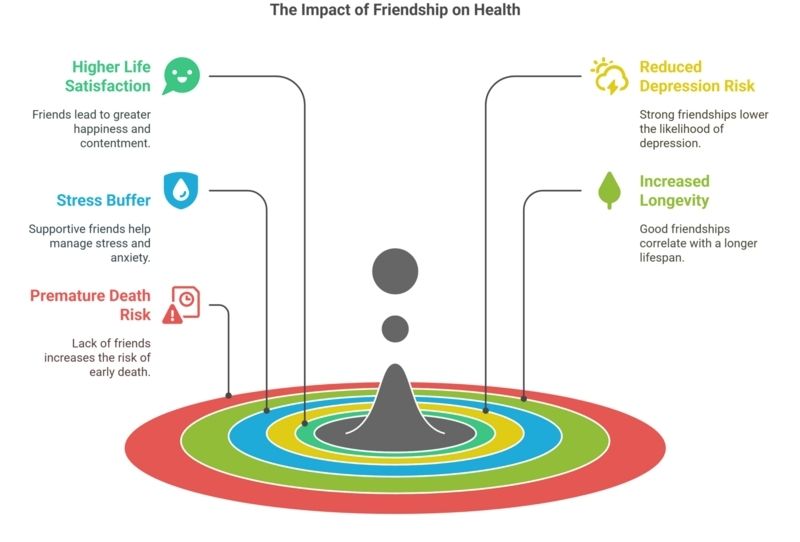

It’s often said that friends are good for your health, and a wealth of research backs this up. Strong social connections are one of the most reliable predictors of a long, healthy, and happy life. Psychologically, people with solid friendships report higher life satisfaction and are less likely to suffer from depression. In one longitudinal study, individuals who had friends and confidants were more satisfied with their lives and had lower risk of major depression over time. The presence of caring friends can buffer against stress and anxiety – for example, adolescents with supportive friends tend to have better mental health in young adulthood. On the flip side, loneliness and lack of friends can be as detrimental as well-known health risks. Psychologist Julianne Holt-Lunstad famously found that weak social ties carry a risk of earlier death comparable to (or even exceeding) the risks of smoking, obesity, and high blood pressure. One meta-analysis of over 300,000 people concluded that people with poor-quality friendships or no friends were about twice as likely to die prematurely as those with strong social circles – a risk effect greater than smoking 15 cigarettes a day. Put simply, friendship isn’t just a feel-good facet of life; it’s a critical component of physical health.

How do friendships exert these powerful effects? For one, friends often encourage health-promoting behavior. A good friend might nudge you to get that lump checked by a doctor, join them in a morning jog, or offer a listening ear instead of you turning to unhealthy coping mechanisms. Friends provide emotional support that can dampen the body’s stress responses – talking with a trusted friend can lower cortisol levels and blood pressure in moments of crisis. There’s even evidence of biological effects: one study found that people with larger social networks had greater resistance to the common cold, likely due to complex interactions between stress, immunity, and social support. Additionally, friendship fulfills basic human needs for belonging and purpose. Having a role as “someone’s friend” – being valued, needed, and cared about – gives a sense of meaning that can motivate individuals to take better care of themselves. In older adults, maintaining friendships has cognitive benefits; social engagement is linked to sharper memory and a lower risk of cognitive decline. All these findings have prompted public health organizations to recognize social isolation as a serious concern. The World Health Organization notes that social isolation and loneliness have a health impact on par with smoking, obesity, and physical inactivity. Consequently, nurturing our friendships is not just a social nicety – it can literally be a lifesaver.

Of course, not all effects are positive: toxic or strained friendships can increase stress and harm well-being, as evidenced by Chopik’s study of older adults where friendships causing stress were linked to more chronic illness. So, the quality of friendships matters more than the quantity. A few close, positive friends will do far more for your health than dozens of superficial or negative relationships.

Types of Friendship and Beyond Binary Classifications

When discussing friendship, people often categorize relationships as “same-sex” vs. “opposite-sex” friendships – essentially, whether you and your friend share the same gender or not. While these classifications have been useful for studying certain dynamics, they also come with limitations and modern critiques. Traditional research on cross-sex (male-female) friendship was frequently based on heterosexual assumptions, focusing on questions like “Can men and women be just friends?” Many studies found that cross-sex friendships often grapple with unique challenges. One common issue is the potential for sexual attraction or tension. In one survey of adults, 62% reported that sexual tension had been present in their male-female friendships. Men, on average, were more likely to say that romantic or sexual interest initiated or complicated the friendship, whereas women more often listed sexual tension as an unwanted aspect that they had to manage. Navigating these feelings (or avoiding acting on them) can be tricky, but plenty of cross-sex friends do remain platonic. Equality can be another hurdle: some scholars pointed out that male-female friendships historically carried the baggage of gender inequality, where societal norms of male dominance could seep in and make true peer equality harder. Thankfully, as gender roles become more equitable, this is less of a barrier for younger generations than it was in the past.

Society’s perceptions have also been a factor. Close friends of the opposite sex often face skepticism (“Are you sure you’re just friends?”), reflecting a cultural assumption that men and women don’t invest deeply in non-romantic relationships with each other. But norms are changing. Men and women increasingly share workplaces, classes, and social spaces, providing more opportunity to develop friendships based on common interests and values rather than gender alone. Many young adults today find cross-gender friendships quite natural, enriched by the different perspectives each person brings.

Critiques of the same-sex/opposite-sex binary in friendship studies argue that it’s an oversimplification. For one, it ignores friendships involving nonbinary or gender-nonconforming individuals, who don’t fit neatly into “same” or “opposite” categories. It also overlooks the role of sexual orientation. A gay man and a straight man might be the “same sex,” but issues of attraction could parallel those in a heterosexual male-female friendship. Conversely, two straight men are “same-sex” friends, but cultural norms for male friendship apply differently than for two straight women friends. In short, gender is only one axis of friendship. Researchers are now exploring a richer tapestry of friendship “typologies”: for example, friendships among LGBTQ+ individuals, cross-age friendships, or intercultural friendships that bridge different ethnic or national backgrounds. Each has its unique dynamics. The key is not to throw out the old categories entirely – gender does shape socialization, and thus friendships – but to be mindful that real-life friendships don’t always fit binary labels. We gain more insight by considering factors like power dynamics, cultural context, and individual personality in addition to gender.

A related debate is the idea of “friends versus more than friends.” Consider the friends-with-benefits arrangement, which is a hybrid of friendship and sexual relationship, or the transition from friendship to romance. These blur the boundaries of how we classify a relationship. They remind us that friendship can sometimes be a foundation for other relationship forms, and the lines can shift over time.

Maintaining Friendships: Strategies and Behaviors

Like any relationship, friendships require maintenance to stay strong. It’s easy to assume good friends will “always be there,” but in reality, busy lives and new obligations can strain even the closest bonds. Social psychologists have identified several key friendship maintenance behaviors that help relationships flourish over time. Four fundamental behaviors are positivity, supportiveness, openness, and interaction. Positivity means keeping your interactions enjoyable – showing affection, joking around, and avoiding constant negativity or criticism. Friends who uplift each other and share laughs tend to stay friends. Supportiveness involves offering emotional and practical help; being there to celebrate successes and to commiserate in hard times. Openness refers to self-disclosure and honesty – trusting a friend with your true feelings and also being receptive when they open up. Finally, interaction simply means time spent together (or in communication). Regular contact, whether through hanging out, phone calls, or even text chains, is the lifeblood of an active friendship. As one researcher put it, friendships “don’t last in a vacuum” – you have to invest time and effort into shared experiences.

Practical friendship maintenance can take many forms. Some friends bond through rituals or routines – maybe a weekly lunch, or an annual trip together – that give them structure to stay in touch. Others practice little gestures of caring, like checking in with a text (“thinking of you, how’s your day?”) or remembering to wish their friend luck before a big exam. Even living far apart, friends can maintain a presence in each other’s lives through social media, video chats, or old-fashioned letters. What matters is consistency and reciprocity: both people contributing to keeping the connection alive. Research on young adults found that those who believed friendships can endure challenges were more likely to use proactive maintenance strategies (like reaching out during busy times) rather than just letting friendships drift.

It’s also important to manage expectations. No friend is perfect, and even best friends will occasionally disappoint or annoy each other. A healthy long-term friendship requires forgiveness and understanding that life circumstances change. As Lise Deguire Psy.D., notes “You will be disappointed. No friend will be perfect, just as you won’t be perfect for them.” Good friends recognize that there may be periods of less contact or times when one person is more giving than the other, but over the long haul there’s a balance. Indeed, having different friends for different needs can help. One friend might be your go-to for emotional support, while another is great for career advice – and that’s okay.

Another aspect of maintenance is boundary-setting. Especially as lives get busy, friends have to negotiate around other priorities (work, spouses, kids). Being upfront about what you can give – and understanding what your friend can – prevents misunderstandings. For example, two new moms might tacitly agree that they’ll catch up when they can, without judgment if one cancels plans due to exhaustion.

Lastly, staying open to new friendships even in adulthood can enrich your social world. New friends don’t replace old ones, but they bring fresh energy and perspectives. Sometimes a “dormant” friendship comes back to life when you reconnect years later or in a new context. The bottom line: friendships are an active relationship. The effort you put in correlates with what you get out, in terms of closeness and longevity. And given the health and happiness benefits discussed, that effort is well worth it.

Conflict, Transgressions, and When Friendships Falter

No friendship is without conflict or transgressions. Because friendships are voluntary and lack formal rules, the “ground rules” are essentially what the friends mutually expect of each other – and these expectations can be breached. Common friendship transgressions include breaches of trust (like betraying a confidence), not “being there” in a time of need, or letting jealousy get out of hand. How friends handle these conflicts can determine the fate of the relationship.

Conflict in friendship can actually be healthy if managed well. Honest communication and forgiveness can lead to a deeper understanding between friends after an argument. For instance, two friends might clear the air after a misunderstanding, each realizing what the other values or feels insecure about, thus coming out stronger. However, some conflicts cut deeper. If a friend seriously violates your values or repeatedly disrespects you, the bond may rupture. Unlike family, we are not obligated to stay friends with someone who treats us poorly; as the saying goes, sometimes you have to “unfriend” for your own well-being. Psychology research on friendship dissolution finds that a major betrayal or persistent negativity often marks the end.

One tricky phenomenon in adolescent friendships is the aforementioned deviancy training – essentially, friends leading each other astray. If conflict arises because one friend is pressuring the other to engage in wrongdoing (skipping school, using drugs, bullying others), it can create a moral dilemma. Often, teens feel torn between loyalty to a friend and their own values or parental rules. Studies by Mary Gifford-Smith et al showed that when adolescent friends spend time reinforcing each other’s deviant talk or behavior, it significantly increases their risk for escalating problem behavior and even criminality. Knowing this, many schools and youth programs now try to disrupt negative peer clusters and encourage more positive friend interactions. It’s a reminder that peer influence is powerful: friends can build us up, but they can also tear us down or lead us into trouble.

What about more mundane conflicts, like two friends drifting apart because one has changed? During transitions (say one friend gets very religious or one becomes engrossed in a new romantic relationship), value mismatches or feeling neglected are common friction points. A friend might feel hurt that you have “no time for them” after a big life change. Addressing this requires empathy on both sides: one friend expressing that they miss the closeness, and the other explaining the challenges they’re juggling and finding a compromise to stay connected.

There’s also the issue of friendship transgressions – actions that feel like a breach of the friendship “code.” Examples include a friend dating your ex without talking to you, or consistently canceling plans last-minute. These can cause feelings of betrayal or devaluation. Often, a sincere apology and effort to make amends can heal the rift if the friendship has a strong foundation. In other cases, repeated transgressions signal that a friendship is unbalanced or unhealthy.

Some friendships experience toxic patterns such as one friend being overly controlling or critical, or engaging in gossip. If a friendship becomes a source of stress or low self-esteem rather than support, it may be time to step back. Ending a friendship can be emotionally tough – there’s no formal script for a “friend breakup” – but sometimes necessary. Psychologists advise handling it with honesty and compassion, much like a romantic breakup: acknowledge the good times, explain why you feel the need to distance, and wish them well. It helps both parties move forward without lingering resentment.

After the Romance: Friendship When Relationships End

One intriguing aspect of adult friendship is what happens after a romantic relationship ends. Can ex-partners be friends? The answer isn’t one-size-fits-all. Many exes do attempt to stay friends, especially if the breakup was mutual or they valued the companionship aspect of their relationship. Researchers have identified a few common motives for maintaining friendships with an ex. One study found four main reasons: security, practicality, civility, and unresolved romantic desire. Security means one or both people find emotional support and trust in the ex-partner (they “know you best”). Practicality covers situations like co-parenting children, shared finances, or overlapping friend groups – staying friendly simply makes life easier. Civility is about politeness and not wanting a dramatic break; perhaps you share a social circle or workplace and it’s just more harmonious to remain on good terms. And unresolved romantic desires means at least one person still has feelings and hopes maybe the friendship could rekindle the romance.

These reasons aren’t equally healthy. Staying friends for practical or civil reasons can work if boundaries are clear (e.g. strictly co-parenting or being courteous at gatherings). Security can be positive too, though it may prevent people from seeking new support if they’re overly reliant on an ex. The trickiest is unresolved desire – in those cases, the “friendship” may be one-sided or a holding pattern, preventing both from moving on. Studies indicate that those who stay friends with exes often have to navigate lingering jealousy or attraction, which can complicate new relationships.

Experts usually advise taking time apart post-breakup before attempting a friendship. Emotions need to cool down and redefine the relationship. This might mean a period of no contact, or only essential contact if you have shared responsibilities. With time, some exes do develop a genuinely platonic friendship that resembles a sibling-like or colleague-like relationship. They may even come to value each other in a new way, free from the expectations of a romance. For example, two people who weren’t compatible as lovers might discover they still enjoy talking about art or supporting each other’s careers as friends.

However, it’s important that both people truly want a friendship for its own sake. If one secretly is hanging on in hopes of reunion, the dynamic can become painful or unfair. Boundaries are crucial: topics like new dating partners, or the level of day-to-day involvement, should be handled with sensitivity. Clear communication helps; some exes explicitly discuss what their friendship will look like (e.g. “We’ll catch up once a month over coffee, but we won’t text every day like we used to”).

Interestingly, whether exes stay friends may also depend on personality and attachment styles. People with secure attachment and low jealousy might transition to friendship more smoothly. Those with high attachment anxiety might struggle, finding it too painful to be “just friends.” Also, cultural norms play a role – some cultures or individuals see remaining friends with an ex as a sign of maturity, while others see it as inviting trouble. Ultimately, friendship after romance can work in many cases, but it works best when the romantic chapter is fully closed for both, and they genuinely value each other as individuals beyond the context of dating. If that balance is struck, an ex can indeed transform into a cherished friend.

Friendship and Mentorship: Blurring Boundaries

Sometimes friendships arise in unlikely places – like between a mentor and mentee. Consider a student who develops a close rapport with a teacher, or a young employee befriending an older, experienced colleague. Mentorship relationships involve a power difference: one person is guiding or advising the other. Yet human nature doesn’t partition our feelings so neatly. It’s natural for genuine affection and camaraderie to grow in a mentor-mentee bond, especially as they spend time together and share personal aspirations or challenges. Many of us have had mentors who eventually felt like friends or even parental figures. And many mentors feel proud and close to mentees, blurring the line between professional role and personal bond.

There’s a positive side to this: a friendship with a mentor can be incredibly fulfilling. The mentee gains not just advice but a caring supporter; the mentor enjoys seeing someone flourish and often learns from the fresh perspective of the mentee. As the mentee matures, the relationship may evolve into one of true equals – for example, a PhD advisor and their student might become lifelong friends and colleagues in the field. This speaks to the voluntary, mutual aspect of friendship extending into the professional or academic realm.

However, boundary management is essential. In formal mentorship (like a therapist-client, teacher-student, or manager-intern scenario), there are ethical lines that shouldn’t be crossed while the formal relationship exists. The American Psychological Association cautions mentors to maintain boundaries and “avoid blurring the relationship’s boundaries and having it morph into the inappropriately personal.”. It’s okay to be friendly and show care, but, for instance, a professor shouldn’t favor their mentee-friend in grades, or a boss shouldn’t let friendship prevent them from giving honest performance feedback. Time and context matter too: grabbing a coffee and talking about life is fine, but going out drinking every weekend might be inappropriate if one person has evaluative authority over the other.

One common solution is transparency and role clarity. Great mentors often openly acknowledge the different “hats” they wear. For example, a mentor might say, “As your friend, I sympathize with your situation; as your supervisor, I still have to enforce this deadline.” Both parties understanding the dual nature can prevent confusion. It’s also advisable that if a deep friendship forms, it might be better nurtured after the formal mentorship period ends (such as after a class is over, or once the person moves to a different department). Then the two can relate without the hierarchy in place.

Cultural factors, like the Power Distance Index (PDI) of a society, influence how mentorship and friendship mix. PDI measures how much inequality and hierarchy are accepted in a culture. In high-PDI cultures, the mentor-protégé relationship might stay very formal (mentor as respected elder, mentee deferring) and not easily shift to friendship, even years later. In low-PDI cultures, it’s more natural to treat mentors “like a friend” and speak openly. Neither is right or wrong, but being mindful of these expectations is key. For instance, a student from a high-PDI culture might feel uncomfortable with an American professor’s informal, buddy-like approach – they might misinterpret friendliness as a loss of respect. Conversely, someone from a low-PDI context might feel a mentor is cold if they don’t allow any personal connection.

When done ethically, friendship and mentorship can enrich each other. A mentor who cares personally will likely go the extra mile to help, and a mentee who feels close may be extra motivated to succeed (not wanting to let their mentor-friend down). Many successful people cite mentors who became lifelong friends as pivotal in their journey. The take-home message is to honor the boundaries that need to be there (especially when there’s a power differential), while still allowing genuine human connection to grow.

Friendship Quality and Mental Health History

Our personal history with mental health can profoundly shape our friendships – and vice versa. Some people carry wounds or patterns from childhood (like trauma, neglect, or anxiety) that affect how they approach friends. For example, someone who grew up emotionally neglected may yearn for close friends as their “chosen family,” as was the case for one author who credited her friends with literally keeping her sane and becoming her support system in place of absent family. Indeed, research suggests that individuals with difficult family backgrounds often rely on friendships for emotional support, sometimes developing exceptional loyalty and empathy towards friends (having learned not to take support for granted). A history of mental health challenges like depression or social anxiety can also impact friendship patterns. Socially anxious individuals might struggle to initiate friendships or fear rejection, leading them to have fewer but very trusted friends. Those with depression might withdraw from friends at times, which friends may misinterpret – it can strain connections if friends feel the person is disengaging or doesn’t care, when in reality they’re just struggling internally. Educating friend groups about mental health can encourage patience and support rather than frustration.

Conversely, high-quality friendships can be a protective factor for mental health. There’s evidence that having close friends in adolescence predicts lower depression and higher well-being in adulthood. Strong friendship support can buffer the impact of stressors that might otherwise trigger a mental health episode. In therapy, clinicians often assess a client’s social support; a person with at least one or two confidants is generally more resilient in recovery from mental illness than someone completely isolated. The famous long-term Harvard Study of Adult Development found that the quality of social relationships was a strong predictor of happiness and health in later life – more so than wealth or fame – and that loneliness was toxic. Good friendships were part of those quality relationships contributing to mental health and even cognitive health.

Mental health history can also influence what one needs from a friend. For instance, someone with a history of trauma might value friends who are very consistent and predictable, because trust is a big concern. Someone who has struggled with self-esteem may do best with friends who communicate appreciation and avoid overly critical or competitive interactions. In some cases, people with certain disorders (like borderline personality disorder, characterized by intense fear of abandonment) may have stormy friendships, with lots of closeness and breakups. Recognizing these patterns can help individuals work on them in therapy and communicate better with friends about triggers.

It’s worth noting that being friends with someone dealing with mental health issues requires empathy but also healthy boundaries. Friends are not therapists (unless they actually are trained, but even then it’s different). Supporting a friend might involve listening or helping them find professional help, but it’s important friends don’t sacrifice their own well-being or feel solely responsible for “saving” their friend. Ideally, friendship is a two-way street – even someone struggling can contribute joy, humor, or perspective to the friendship, not just receive help. Many people with mental health histories are incredibly caring and insightful friends due to their experiences.

Stigma plays a role: historically there has been stigma around mental illness that could impede forming friendships (e.g. someone hiding their struggle for fear of rejection). As society becomes more open about mental health, friends are increasingly willing to talk about depression, ADHD, trauma, etc., and accommodate each other’s needs. This openness can deepen friendships. For example, a friend saying “I’ve been having panic attacks, so I might leave the party early if I get anxious” allows friends to support rather than be offended at an early exit. Overall, friendship and mental health are deeply interlinked – nurturing one can often benefit the other.

Competition Within Friendships

Friendship is usually thought of as a cooperative, supportive bond – so what happens when competition creeps in? Competition within friendships is a common but complicated phenomenon. A bit of friendly rivalry can be motivating and harmless (think of two friends pushing each other during a workout, or playfully vying in fantasy football). But a competitive friendship goes further: it’s a friendship where the normal warmth and support are overshadowed by a constant need to one-up each other. In such cases, instead of mutual celebration of success, a friend might secretly (or openly) feel envious or threatened when the other achieves something.

Psychologists note that some competitiveness is natural – we often compare ourselves to peers as a way to gauge our own progress (social comparison theory). But problems arise when a friend becomes more of a rival than an ally. Signs of unhealthy competition include: turning every conversation into a brag session or contest, downplaying the other’s achievements, or even sabotaging each other’s success. It can be subtle – for example, a friend might always bring the discussion back to their life when you share good news, or they might imitate and try to outdo your choices (you get one tattoo, they quickly get two).

Competitive dynamics can be influenced by gender socialization. Men may be more openly competitive in groups (think sports or teasing), yet because men sometimes “expect less” from friendships emotionally, they might not perceive competition as a threat to the relationship. Women, who often emphasize equality and closeness in friendship, might feel more distressed by competition or try to hide it to maintain harmony (leading to passive-aggressive behaviors or internalized jealousy). A study on interpersonal competition in friendships found that both men and women experience it, but they might handle it differently – men sometimes use direct competition as a way to bond (e.g. trash-talking each other in good fun), whereas women might engage in more comparison and self-evaluation, potentially feeling inadequate if competition arises.

So is competition all bad? Not necessarily. If both friends have a similar drive and keep it respectful, they can motivate each other to grow. Two friends in the same career field might push each other to achieve (think of friendly academic rivals who study together and rank top of the class). The key is maintaining mutual respect and support – celebrating each other’s wins genuinely, and keeping competition in perspective. Healthy competition should never devolve into rooting for your friend to fail. If you find yourself in a friendship where you or your friend are feeling constant envy, it’s important to address it. Often, an honest conversation can defuse the tension: admitting “I realized I’ve been feeling jealous when you talk about your new relationship, and I hate that – you deserve happiness, so I want to work through this,” can be a vulnerability that brings friends closer. True friends can acknowledge such feelings and reassure each other rather than exploit vulnerabilities.

In cases where one friend is excessively competitive and unsupportive – perhaps even delighting in outshining you – you may be dealing with a toxic dynamic. Some individuals with high Machiavellian or narcissistic traits treat friendships as zero-sum games, which is not sustainable for real trust. Setting boundaries or distancing might be necessary if a friend consistently makes you feel inferior or stressed. Life is not a competition, and friendship certainly shouldn’t feel like one. Ideally, your accomplishments and your friend’s accomplishments become a source of mutual joy. A good mantra is “comparison is the thief of joy.” Friends who find themselves comparing too much might practice focusing on gratitude and the distinct paths each person is on, rather than keeping score on a single yardstick.

Conclusion

Friendship is a rich and multifaceted aspect of human life. From childhood playmates to confidants in our old age, friends shape our identities, share our joys and sorrows, and even influence our health. The psychology of friendship reveals that these bonds are not “one size fits all” – they vary across life stages, between genders, across cultures, and within each unique pairing of individuals. Understanding the nuances – why a teenage bond might falter, how a cross-sex friendship can thrive without romance, why your best friend might feel like a competitor at times, or how to maintain a lifelong connection – can help us navigate our own friendships more mindfully.

At its heart, the value of friendship is clear: humans are social creatures, and good friends fulfill essential needs for belonging, support, and meaning. They can literally extend our lives and make those lives worth living. As you deepen your knowledge of psychology, remember that even the most academic theories (attachment styles, self-construals, cultural indices) ultimately circle back to everyday experiences – like a comforting chat with a friend on a bad day. By applying insights from research – communicating openly, respecting differences, investing time, setting healthy boundaries – we can all become better friends and cultivate the kind of friendships that enrich our lives.