Psychological Torture:

What It Is, How It Works, and Its Human Cost

⚠️ Content Advisory. This article discusses psychological torture, including trauma, coercion, and human rights abuse. reader discretion is advised.

🎥 Watch the short video below for a quick, powerful overview of psychological torture. Then scroll down to explore the full article for a deeper dive into a topic that is essential for psychologists, legal systems, and human rights advocates to understand.

Introduction

Psychological torture – sometimes called "no-touch" torture – refers to abuse techniques that inflict extreme mental suffering while often leaving few physical marks. Unlike beatings or other obvious violence, these methods work on the mind, undermining a victim’s sanity and sense of self. Yet their effects can be just as devastating as physical torture, raising urgent questions in psychology and ethics. In this article, we explore what psychological torture is, how it’s implemented, its impacts on survivors’ minds and brains, its history in U.S. policy, and why it remains such a contentious issue. We conclude with critical reflections and research ideas for psychology students – the next generation of professionals who must grapple with these realities. .

What Is Psychological Torture?

Defining the term: Legally, torture is defined broadly to include “any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted” for purposes such as coercion or punishment. In other words, international law (e.g. the UN Convention Against Torture) explicitly recognizes severe psychological abuse as torture. Clinically, psychological torture involves deliberate actions that inflict fear, isolation, or profound mental trauma. It relies primarily on psychological effects – manipulating a person’s environment, perceptions, and mind – and only secondarily (if at all) on direct physical harm.

“No-touch” methods: Historically, interrogators developed techniques to break people without obvious injury – hence the term no-touch torture. During the Cold War, research by the CIA and others led to a suite of methods targeting the victim’s psyche. For example, in the 1950s Research sociologist Albert Biderman studied POWs from the Korean War and identified “dependence, debility, and dread” as key forces to break a prisoner’s will, as part of what he called the Chart of Coercion. U.S. interrogation manuals built on these insights, systematically attacking all of the human senses in the subject. In essence, psychological torture aims to shatter an individual’s mental stability and autonomy. It often causes victims to feel responsible for their own suffering, which can make them capitulate more readily to their torturers. This insidious approach – leaving few external scars – has been viewed by its architects as a way to torture in secret or with deniability. But as we see next, the costs to the human mind and brain are severe.

Key Techniques of “No-Touch” Torture

Psychological torture encompasses a range of techniques. Below are some of the most common, often used in combination:

- Sensory Deprivation and Overload: Interrogators may blindfold or hood detainees, keep them in darkness or constant bright light, and muffle or bombard them with noise. By “monopolising perception” – cutting off normal sight, sound, and sensation – they create disorientation and panic. Conversely, they might use sensory over-stimulation (e.g. blaring sound, strobing lights) to overwhelm the victim. The goal is to unmoor the person from reality, inducing confusion and helplessness.

- Isolation: Solitary confinement is a cornerstone of psychological torture. Captives are kept utterly alone, sometimes for weeks or months, with no social contact or information from the outside world. This extreme isolation often results in anxiety, hallucinations, and cognitive breakdown. Many survivors report that prolonged solitary “becomes worse than physical beating”. In one case, a detainee tweeted that after long isolation his “cognitive skills have been greatly & permanently diminished”. Total isolation destroys the normal social and sensory inputs the brain needs, causing intense suffering.

- Threats and Induced Fear: Torturers frequently threaten to kill, injure, or otherwise harm the victim or their loved ones. Mock executions (staging a fake execution of the prisoner) are an extreme example designed to terrorize. Such strictly fear-inducing methods prey on primal survival instincts – the victim never knows if the threat is real or when it might be carried out. Even without laying a hand on the prisoner, the psychological trauma of constant death threats, sham executions, or hearing others being tortured can be profound.

- Humiliation and Degradation: Many psychological torture regimes seek to strip away the person’s dignity. Tactics include verbal abuse, sexual humiliation, and cultural or religious insults – for example, forced nudity, derogatory slurs, or desecration of religious items. These methods attack the victim’s identity and self-worth. By destroying the subject’s normal self-image through shame and degradation, torturers further destabilize their mental state. Notably, techniques like forced nudity and humiliation were infamously documented in photos from Abu Ghraib prison, illustrating how tormentors use shame as a weapon.

- Sleep Deprivation and Stress Positions: Denying a person sleep for days on end, or forcing them to maintain painful postures (such as standing handcuffed to the ceiling), causes extreme exhaustion and pain. These are sometimes called “self-inflicted” pain techniques – the torture comes from the victim’s own body protesting its limits. The CIA’s psychologists found that combining sleep deprivation with stress positions and other discomforts could rapidly break down resistance. The result is delirium, impaired thinking, and physical collapse. A person kept awake for 48–72 hours, especially under duress, experiences drastic cognitive impairment (memory lapses, confusion) and even hallucinations. Indeed, even a few days without sleep can “fog the mind,” and coupled with sensory disorientation it may bring on psychotic symptoms.

Each of these techniques alone is damaging, but torturers often use them in concert. For example, a detainee might be stripped naked, held in a dark silent cell alone, deprived of sleep, and periodically subjected to terrifying threats. The cumulative effect is to erode the victim’s sense of reality, security, and self – essentially breaking the person from within.

Psychological and Neurobiological Impacts on Survivors

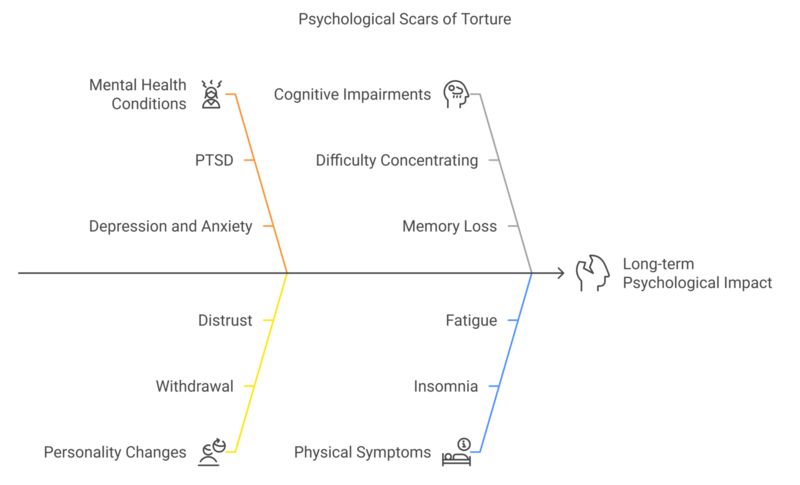

Tactics that leave no visible wounds can nonetheless inflict deep psychological scars. Survivors of psychological torture commonly develop serious mental health conditions. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is frequently observed, with symptoms like flashbacks, nightmares, hypervigilance, and emotional numbing. Depression and anxiety disorders are also widespread, as survivors struggle with fear, panic attacks, and despair long after the torture ends. In some cases, personality changes occur – a once-outgoing person may become withdrawn, distrustful, or unable to experience pleasure (anhedonia). Clinicians have noted that difficulty concentrating, memory loss, insomnia, fatigue, anxiety, depression, and PTSD are all long-term sequelae of torture in general, and often especially pronounced after psychological torture. In fact, one treatment center for torture survivors reports that psychological torture can be more damaging and longer-lasting than physical torture in its impact.

From a neurobiological perspective, chronic extreme stress is devastating to the brain and body. Torture puts the victim in a state of sustained “fight or flight” – a flood of stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline that, over time, disrupt the body’s homeostasis (its normal equilibrium). Neuroscientists note that intense fear and stress can physically alter brain structures involved in memory and emotion. For example, prolonged trauma may damage neurons in the hippocampus (crucial for forming memories) and heighten reactivity in the amygdala (the fear center). “The brain is never the same as it was before.” This helps explain why survivors often have trouble concentrating or recalling information: the torture experience can literally rewire their neural circuitry in maladaptive ways.

Survivors also commonly experience psychosomatic and cognitive problems. They may suffer headaches, dizziness, and impaired cognitive function long after torture. One former detainee, after enduring long-term solitary confinement, described permanent cognitive impairment – an inability to focus or think as he once did. Research has found that extreme stress and trauma “undermine the very ability to think”, as psychologist Dr. Steven Reisner puts it. Sleep deprivation, for instance, triggers hallucinations and confusion; sensory disorientation can induce paranoia. In essence, psychological torture attacks the mind’s foundational capacities – to remember, to reason, to trust what is real. The “worst scars are in the mind,” as one International Red Cross review concluded, and those scars may endure for years or a lifetime.

It’s important to emphasize that these mental injuries are no less real or serious than broken bones or bruises. PTSD, depression, and cognitive deficits from torture can disable a person’s ability to work, socialize, or live a normal life. Furthermore, recovery is often a long, arduous process requiring trauma-focused therapy and support. Unfortunately, because psychological torture leaves no obvious marks, survivors sometimes struggle to prove their suffering – whether in asylum claims or courts – compounding the harm with injustice. The hidden nature of “no-touch” harm makes it a particularly insidious form of abuse, one that challenges our moral and clinical understanding of trauma.

From the CIA’s Cold War Labs to the War on Terror: A Brief History

Psychological torture as we know it today did not arise by accident – it was systematically researched and refined, notably by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). In the early 1950s, alarmed by reports that American POWs in Korea had been “brainwashed” by Chinese interrogators, the CIA launched a top-secret mind control research program code-named MK-ULTRA. CIA-funded experiments explored hypnosis, drugs like LSD, electroshock, and sensory deprivation in an effort to understand and control the human mind. Over time, this research shifted focus from sci-fi-esque mind control to more practical methods of breaking prisoners’ resistance. By the late 1950s, CIA-backed psychologists (often working in universities or the military) found that a combination of sensory deprivation and self-inflicted pain (e.g. enforced stress positions) could effectively shatter a person’s will. Unlike conventional beatings, which obviously injure the body, this approach targeted the mind, exploiting the victim’s own physiology (like pain from holding a position) and psychological vulnerabilities. As historian Alfred McCoy describes, the “no-touch torture” method that emerged causes victims to feel responsible for their pain, making them more likely to comply with their captors’ demands.

In 1963, the CIA distilled all this research into a notorious interrogation manual codenamed KUBARK (a CIA cryptonym for itself). The KUBARK Counterintelligence Interrogation manual laid out a detailed guide to psychological torture techniques. It endorsed tactics such as isolation, sleep and sensory deprivation, threats and fear, and humiliation – explicitly to produce “debility, disorientation and dread” in captives. The manual even advised using “isolation for several days” before interrogation to heighten the prisoner’s anxiety. These methods were disseminated and taught to U.S. allies. For example, a later CIA manual, the 1983 Human Resource Exploitation guide (used in Latin America), was largely copied from KUBARK. Throughout the Cold War, the U.S. (through programs like Project X and the School of the Americas) trained foreign militaries in torture techniques, including psychological approaches, as part of counterinsurgency and anti-communist efforts Sadly, this contributed to the spread of torture regimes in Latin America and elsewhere in the latter 20th century.

The use of psychological torture by the U.S. came home to roost in the Vietnam War. The CIA’s Phoenix Program in Vietnam (late 1960s) combined brutal physical and psychological torture in an effort to destroy the Viet Cong insurgency. Prisoners were subjected to tactics from the CIA playbook – sensory deprivation, stress positions, etc. – alongside extreme physical abuse. The results were ghastly (thousands died or were broken), yet intelligence gains were minimal; even the CIA later admitted the program was an intelligence-gathering failure. Despite its failure, Phoenix became a template for terror: its methods lived on in U.S. training and were exported to other conflicts.

Fast-forward to the post-9/11 era. After the 2001 terrorist attacks, the U.S. once again turned to the arsenal of psychological torture. The CIA, with help from contract psychologists, designed the so-called “enhanced interrogation techniques” used on detainees in secret prisons and at Guantánamo Bay. These methods were not new; they were drawn directly from the Cold War manuals and research – a fact openly acknowledged years later. The Senate Intelligence Committee’s 2014 report on CIA interrogations revealed that detainees were subjected to extended sleep deprivation, isolation, stress positions, and waterboarding, aimed at inducing a state of “learned helplessness”. (Learned helplessness, a concept from psychology experiments in the 1960s, describes how subjects exposed to unavoidable pain eventually stop trying to escape, essentially giving up hope. Torturers attempt to recreate this effect in prisoners.) The United States government, in the 2000s, made extensive use of psychological torture techniques – effectively resurrecting the CIA’s old playbook. This occurred even as top officials euphemistically denied “torture” was happening, highlighting a troubling gap between language and reality.

Importantly, the involvement of medical and psychology professionals has been documented throughout these programs. In the Cold War era, doctors and psychologists aided in developing and sometimes administering psychological torture. In the post-9/11 program, two psychologists not only crafted the CIA’s tactics but personally oversaw interrogations. This collusion of health experts lent a sheen of scientific credibility to abuse – a profound ethical breach that the profession is still grappling with.

Ethical and Legal Controversies

The use of psychological torture by the U.S. and others has fueled intense ethical and legal debate. International law is unambiguous: torture, whether physical or psychological, is absolutely prohibited. The UN Convention Against Torture, which the U.S. has ratified, bans cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment and recognizes mental suffering on par with physical pain. Under these standards, many “no-touch” methods (prolonged solitary confinement, threats, etc.) clearly qualify as torture. Yet, contradictions in U.S. policy emerged, especially in the early 2000s. Justice Department memos at the time attempted to narrowly redefine torture – for example, suggesting that only pain leading to organ failure or death, or mental pain causing “prolonged mental harm,” would count as torture. This effectively carved out a legal space for psychological techniques that might not leave provable long-term injury. Critics blasted this as a cynical misinterpretation. By requiring a victim to show lasting mental damage, the U.S. policy “inverts the absolute prohibition on torture by introducing a 'wait and see' approach” – in other words, something might be allowed until it causes obvious trauma. Such legalistic maneuvers undermined international law and, many argue, America’s moral standing.

Ethically, psychological torture poses stark dilemmas. For one, it challenges the notion that torture can ever be “less bad” if it doesn’t break bones. Survivors and human rights experts insist that “torture is torture,” and methods like isolation or mock executions are no more acceptable than beating or burning. The American Psychological Association (APA) faced scandal when it was revealed that some psychologists had helped facilitate CIA and military interrogations, blurring professional ethics. This spurred reforms to ensure psychologists “do no harm” and are not complicit in detainee abuse. Even beyond professional circles, the morality of using techniques that cause mental anguish has been hotly debated in the public sphere, especially when officials claimed such methods were necessary for security.

Another controversy is the lack of accountability for psychological torture. Because it leaves less visible evidence, perpetrators often escape justice. A stark example is the case of Maher Arar, a Canadian citizen who in 2002 was secretly sent by U.S. authorities to Syria, where he endured grave psychological torture (and some physical abuse). Arar later sought legal redress in U.S. courts, but his case was dismissed on national security grounds. His failed attempt to obtain justice is one of many instances where governments have refused to confront the torture done in their name. This impunity sends a dangerous signal. It also puts psychologists and health workers in the spotlight: Will they stand up against practices that violate human rights, or stay silent under pressure? Historian Alfred McCoy has pointed out a further moral cost – “no-touch” torture harms not just victims but also corrodes the perpetrators’ humanity. Ordering or inflicting mental torture can inflict moral injury and psychological strain on those who carry it out, a fact often overlooked.

Psychological torture lies at a fraught intersection of law, policy, and ethics. The international community widely condemns it, yet some nations have tried to exploit gray areas. The ethical consensus in medicine and psychology is that participation in torture is fundamentally wrong – yet the very skills of psychologists were misused to design these torments. This topic forces us to confront how easily definitions can be bent in times of fear, and it challenges professionals to uphold ethical principles even when told “national security” is at stake.

Does Psychological Torture “Work”? Interrogation Effectiveness in Question

Behind the resort to torture is usually a purported goal: to extract valuable information or confessions. But does psychological torture actually produce truthful, useful information? Decades of experience and research say no – in fact, such methods are often counterproductive. Forensic psychologist Dr. Gavin Oxburgh, an interrogation expert, emphasizes that torture is “immoral, ineffective and illegal.” He notes that coercive techniques tend to yield false information, as the victim will say anything to stop the pain, whereas humane, rapport-building techniques elicit far more accurate intelligence. This view is echoed by many in law enforcement and military interrogation: a cooperative, respectful interview is more likely to get the truth than an individual terrorized and confused by pain.

Scientific findings back this up. Extreme stress and fear impair the very cognitive functions needed to recall facts. Neurobiologist Shane O’Mara, for instance, has shown that high levels of stress hormones degrade memory retrieval – essentially, torture “scrambles” memory and leads to unreliable accounts. As noted earlier, enough stress can even cause brain damage in memory systems. A detainee in a state of panic, sleep-deprivation, or hallucination is likely to produce disoriented, inaccurate statements. Intelligence agencies have found that leads obtained under torture are frequently “corrupted information” that waste time or send investigators down false paths. Historical examples bear this out: the French in Algeria, the CIA in Vietnam’s Phoenix Program, and the U.S. after 9/11 all found that torture did not yield the hoped-for actionable intelligence, but did inflict lasting trauma and tarnish their reputation.

Conversely, non-coercive methods have proven highly effective. Skilled interrogators build rapport, use strategic questioning, and exploit cognitive cues – an approach sometimes called Investigative Interviewing or the PEACE model (originating in the UK) – to obtain information without abuse. These methods not only respect human rights but often glean richer, more reliable details. As Dr. Oxburgh points out, when interrogators “use humane, rapport-building techniques, you get better and more accurate information”. This aligns with what many experienced interrogators say: a subject who trusts you or at least doesn’t fear you may speak truthfully, whereas one who is terrorized will tell you whatever they think you want to hear.

It’s also worth noting that torture – psychological or physical – can backfire by hardening the resolve of detainees or serving as a propaganda tool for enemies. The moral outrage it generates can fuel further conflict or radicalization. Thus, from a strategic perspective, the consensus of experts and ethical leaders is that torture is not only wrong but ineffective and counterproductive. In 2017, the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture concluded plainly: torture during interrogations is illegal, immoral, and ineffective – it “produces contaminated information” and undermines legitimate law enforcement. Psychological torture, despite its cunning cruelty, is no exception. In the final analysis, the myth that torture works has been debunked by science and history. What remains are shattered lives of survivors and a cautionary tale about abandoning our core values.

For Psychology Students: Critical Thinking and Research Directions

As students of psychology – and future practitioners – it’s crucial to reflect on the role of our discipline in issues like interrogation and torture. Psychology offers powerful insights into human behavior, which can be used for healing or, sadly, for harm. Here are some points and questions to consider, as well as ideas for further research:

Critical Thinking Points:

- Ethical Responsibility vs. Authority: How should psychologists respond if asked to apply their skills in harmful ways (e.g. designing an interrogation plan that inflicts mental harm)? Consider the lessons of history: many torturers relied on behavioral science. What is your ethical duty to “do no harm” in real-world applications, and how would you handle pressure from authorities or employers?

- Defining Torture – Gray Areas: Reflect on where you would draw the line between legitimate interrogation and psychological torture. Are techniques like solitary confinement or sleep deprivation always unethical? Psychological tactics are sometimes portrayed as more humane; do you agree, or is this a dangerous misconception?

- Psychological Impact and Empathy: In working with trauma survivors, how can psychologists validate and treat injuries that are invisible? Consider the profound neuropsychological effects of torture – what does this teach us about the mind-body connection and the importance of mental health in human rights?

- Real-World Ethics in Research: Psychological research itself (e.g. stress experiments, conditioning studies) has occasionally been misused for unethical purposes. How can future researchers ensure their work isn’t twisted into tools of abuse? Should there be greater oversight or moral deliberation in high-impact research areas (like interrogation, behavior modification, etc.)?

- Global and Cultural Perspectives: Torture often occurs in contexts of war, terror, and cultural conflict. How might cultural biases play into what techniques are used or justified (for instance, exploiting religious taboos as torture)? And how can international professional communities (like psychologists worldwide) unite to condemn and prevent all forms of torture?

Research Project Suggestions:

- Study on Interrogation Techniques: Design a comparative study (perhaps via simulation or archival case analysis) examining outcomes of rapport-based interviewing vs. coercive interrogation. For example, you could analyze police interview records or military reports to see which approach yields more consistent, verified information. This could be a literature review of known cases, or a proposal for an experimental setup (ethical and mild, of course) to test how stress affects subjects’ recall accuracy.

- Impact of Solitary Confinement on Cognition: Propose a research project using neuropsychological tests or brain imaging to assess the cognitive effects of isolation. For instance, working with volunteers in a short-term simulated solitary confinement (with full ethical safeguards), measure changes in memory, attention, and mood. Alternatively, conduct a qualitative study interviewing former prisoners who endured long solitary confinement, documenting their mental health outcomes. This research can illuminate the specific cognitive impairments (memory loss, difficulty concentrating, etc.) linked to sensory and social deprivation.

- Treatment and Rehabilitation of Torture Trauma: Conduct a literature review on therapeutic interventions for survivors of psychological torture. What does current research say about effective treatments for PTSD and depression in this population? Are specialized therapies (e.g. trauma-focused CBT, EMDR, group therapy) successful in addressing the unique features of torture trauma? Identifying gaps in treatment research could lead to an experimental study – for example, testing a novel intervention to help restore cognitive function or reduce nightmares in torture survivors.

- Ethical Decision-Making in Psychologists: Consider a research project that surveys or experiments on how professionals make ethical choices under authority pressure. You might present psychology graduate students or practitioners with a hypothetical scenario involving national security and “enhanced” interrogation, then explore what factors (training in ethics, personal morals, group influence) affect their willingness to participate or object. Understanding these dynamics could inform ethics education to prevent future complicity in human rights abuses.

Psychological torture is a challenging and sobering topic, sitting at the crossroads of psychology, law, and human rights. By understanding its mechanisms and consequences, we not only bear witness to the suffering of survivors – we also equip ourselves to speak out against such practices and ensure our science is used to heal, not harm. For psychology students and professionals, the call is to remain vigilant and compassionate, upholding ethical principles even in the face of “no-touch” cruelties that others might not see. In shining a light on psychological torture, we affirm the resiliency of the human spirit and the imperative to protect it, no matter the circumstances.

Know someone who would be interested in reading Psychological Torture: What It Is, How It Works, and Its Human Cost.

Share This Page With Them.

Go From "Psychological Torture: What It Is, How It Works, and Its Human Cost" Back To The Home Page