Interview With Claudia Hammond

Claudia Hammond is an award-winning broadcaster, writer and psychology lecturer. She presents the critically acclaimed All in the Mind & Mind Changers series on BBC Radio 4, and also the BBC World Service series "The Truth About Mental Health?"

Claudia regularly appears on TV to discuss research in psychology, and is on the part-time faculty at Boston University's London base where she lectures in health and social psychology.

Q & A

According to the BBC website you make it your mission to slay common myths about the brain and its workings. Which brain myth would you say is the most pervasive and why?

The myth that we only use 10% of the brain is one which just won't go away. We love the idea that we have this untapped 90% of potential and that if only we could activate a bit of this we could be cleverer, faster and better. I'd like that too, but sadly it just isn't true.

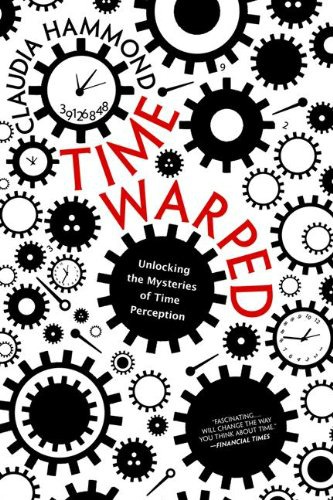

Could you tell us about your book Time Warped?

In Time Warped I wanted to explore the way that we perceive time - why it is, for example, that time slows down when you're terrified and appears to speed up as you get older. Along the way I realized the extraordinary lengths that researchers have gone to in exploring this topic - throwing people backwards off tall towers, persuading them to steer themselves blind-fold towards a precipice and even living alone in an underground ice-cave for two months at a time without a wristwatch.

|

I've gathered what I consider to be the best research on time perception from around the world and having studied it, I for one, will never think about time in the same way again. |

|

You're quoted as saying that the great thing about your job is "getting to interview some of the most brilliant researchers in the world." Do you have a favorite interview?

It's difficult to pick one. Interviewing Philip Zimbardo was certainly memorable because he's so entertaining. We went to his house at the top of the famous zig-zag street in San Francisco where he cooked pizza for us. Each floor of his house had a balcony with a better view than previous one. But in terms of talking about their research it was great to meet Elizabeth Loftus. She's been so determined to use her findings for the good and hasn't been afraid to speak out even when that attracted considerable hostility.

I was also really glad to have interviewed the British psychologist Richard Gregory, not long before he died. He was so wise and I could tell he was really thinking seriously about each of the questions I'd asked him. James Pennebaker is another favorite.

What can listeners expect from your BBC World Service series "The Truth About Mental Health?"

The idea of this series is to look at different approaches to mental health care around the world and to ask whether what works in one place will work in another. I've been to Jordan to meet Syrian refugee children who are learning remarkably simple strategies to help them to cope with the appalling situations they've witnesses. Then in Japan I met the so-called "hikkikomori" - young people, mostly men who choose to stay inside their rooms, often for years at a time. I explore whether this is a mental health problem at all and how culture shapes the way we respond to distress.

In Norway I interviewed people whose lives were changed forever when Anders Brevik shot so many young people on the island not far from Oslo and exploded a bomb in a city centre. Those are interviews I will never forget.

Having presented an All in the Mind special about the Behavioural Insights Team within the UK government were you more or less convinced of the potential of behavioural economics to help inform and shape major public policy?

This is an interesting question. Some of the schemes the team has introduced are very clever and considering that most studies in behavioural economics have been conducted on relatively small samples I think it's brave to try them out on a nation. They've shown that they can work and have already saved money. But these are isolated policies.

I'd like to see a time where it's routine to consult psychological research when bigger policy decisions are made. For that to happen think tanks and governments would need to begin employing psychologists as a matter of course and psychologists need to find ways of making their research more accessible. Policy-makers have said to me that they don't know where to get hold of the latest thinking amongst psychologists on a particular topic and I have some sympathy with that.

If you could interview one psychologist from the past who would it be?

I'd choose William James because the range of topics he covered was extraordinary and he seemed to predict so much that researchers discovered later. He had so much to say in both the areas I've looked at in detail - emotions and time perception - and yet this is a fraction of his work.

In your book Emotional Rollercoaster you chose nine emotions to explore in detail i.e., fear, sadness, anger, happiness, disgust, hate, jealousy, love, sympathy and guilt. Psychologically speaking which emotion did you find most interesting?

I found hope particularly compelling because it's an emotion which tends to get neglected. Not all researchers define it as emotion, yet we do know what it feels like and the impact it can have on health, academic success, happiness and job prospects is surprisingly powerful. I'm interested in how we can feel optimistic while avoiding false hope. How can we temper our expectations with realism.

What's the best thing about being a psychology lecturer?

When you present radio programmes the feedback you get is delayed, so what I like about talking with students is that they are a live audience and they never cease to stop making me think because they raise questions I'd never even thought of.

In terms of having an accurate grasp of the discipline, how would you rate public understanding of psychology?

(Photo Credit: duncan c Via Flickr Creative Commons)

There is definitely an appetite for psychology among the general public and it's something I've seen increasing. I think that there are often two images of psychologists - as therapists or as people doing research on topics which are fairly inconsequential, because these are often reported in the media.

I'm not sure that everyone realizes the range of topics that psychological research covers and that how relevant it can be to society and social policy in particular. Policy committees and enquiries are far more likely to take advice from economists, for example, than psychologists. I think psychologists need to do more to engage with the public and get their research out there so that it's used.

What projects are you currently working on?

I've just finished making the latest series of Mind Changers for BBC Radio 4. This time we've made documentaries on James Pennebaker, Abraham Maslow and Anna Freud. Then a new series of my BBC Radio 4 programme on psychology, mental health and neuroscience All in the Mind begins after that. I'll also be making a programme asking what the perfect office would look like if you were guided by psychological research on what helps us to concentrate, yet work creatively and engage with our colleagues.

In the autumn I'm curating some events at the Royal Institution in London where I have the privilege of being allowed to choose the topics for discussion in the famous Faraday lecture theatre. So I'm planning to ask whether psychology can change the world and if it can, why it doesn't? Should be good.

Connect With Claudia Hammond

Click Here to visit Claudia's website

Click Here to connect with Claudia on Twitter.

Click Here to listen to All in the Mind, the BBC radio series presented by Claudia which explores the limits and potential of the human mind.

Click Here to listen to Mind Changers, the BBC radio series presented by Claudia which explores the development of the science of psychology during the 20th century.

Recent Articles

-

Psychology Articles by David Webb

Jan 26, 26 04:52 AM

Discover psychology articles by David Webb, featuring science-based insights into why we think, feel, and behave the way we do. -

Why Doing Nothing Feels So Hard | Psychology of the Restless Mind

Jan 26, 26 04:42 AM

Why does doing nothing feel uncomfortable? Psychology research reveals how attention, the default mode network, and unstructured thought shape inner restlessness. -

Online Psychologist Australia: 7 Benefits of Choosing Online Therapy

Jan 22, 26 03:26 PM

Discover 7 key benefits of choosing an online psychologist in Australia, from better access and privacy to flexible scheduling and continuity of care.

Go To The Psychology Expert Interviews Page