The Psychology of Trust: Why We Believe and How It Shapes Us

Introduction: The Power and Fragility of Trust

Imagine a world where every handshake required suspicion, every promise came with a lawyer, and every act of kindness was scrutinized for hidden motives. Such a world would grind to a halt. Trust is the invisible glue binding human societies, the psychological foundation upon which relationships, communities, and institutions are built. It allows us to feel safe, collaborate, love, and innovate. Yet, trust is also remarkably fragile – easily broken by betrayal, deception, or inconsistency. This article delves into the psychology of trust, exploring what drives our decision to place faith in others, how this fundamental process develops, and the profound impact it has on our relationships, behaviour, and mental well-being. Guided by the central question – "What drives our decision to trust, and how does that shape our relationships and behavior?" – we will journey through classic theories, cutting-edge neuroscience, and practical implications for understanding this core human experience.

What Is Trust in Psychology?

At its core, trust in psychology is defined as a psychological state involving the willingness to accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the intentions or behaviour of another person. It's not merely optimism; it’s a calculated or felt risk taken in reliance on someone else.

Rotter's Foundational View: Julian Rotter, a pioneer in trust research, conceptualized it as a generalized expectancy. In 1967, he developed the Interpersonal Trust Scale, measuring the extent to which individuals believe others' promises and expect fairness and honesty. Rotter saw trust as a relatively stable personality trait influencing how we interpret others' actions.

Attachment Theory's Blueprint: John Bowlby's Attachment Theory provides a crucial developmental perspective. Our earliest relationships with caregivers form internal working models – mental templates about the reliability and responsiveness of others. A secure attachment fosters a basic expectation that the world is trustworthy; insecure attachments (anxious or avoidant) can lead to chronic difficulties trusting others or needing excessive reassurance. These models act as filters through which we interpret later social interactions.

Beyond Traits: A Dynamic Process: Modern views see trust as more dynamic than Rotter's trait perspective. It's influenced by specific relationships, situational factors, and ongoing interactions. Trust involves cognitive assessments (evaluating someone's competence and integrity) and emotional components (feeling safe and secure).

Why Is Trust So Important in Relationships?

Trust is the bedrock of healthy, functioning relationships across all domains. Its importance stems from enabling:

1. Vulnerability and Intimacy: Trust allows us to lower our emotional guards, share our true selves – fears, dreams, insecurities – without fear of ridicule or exploitation. This vulnerability is essential for deep connection in romantic partnerships and close friendships.

2. Emotional Safety: In a trusting relationship, we feel psychologically safe. We believe our partner, friend, or colleague has our best interests at heart and won't intentionally harm us. This safety net is crucial for mental well-being.

3. Cooperation and Collaboration: Trust reduces the perceived need for constant monitoring and safeguards. In teams (work, sports, community), trust enables effective collaboration, knowledge sharing, and coordinated effort towards common goals. Without it, energy is wasted on suspicion and conflict management.

4. Conflict Resolution: When trust exists, conflicts are more likely to be seen as problems to solve together, rather than battles to win. There's a baseline belief in the other person's goodwill, making constructive resolution possible.

Example: A manager who trusts their team delegates effectively, empowering members and fostering innovation. A team member who trusts their manager feels comfortable raising concerns early, preventing small issues from escalating. Distrust in this dynamic leads to micromanagement, withheld information, and stifled progress.

How Is Trust Built?

Trust isn't bestowed instantly; it's painstakingly constructed brick by brick through consistent, observable behaviour. Key ingredients identified by psychological research include:

- Consistency and Reliability: Doing what you say you will do, time and again. Reliability in small things (showing up on time) builds confidence for reliability in larger things. Inconsistency breeds doubt.

- Transparency and Honesty: Being open about intentions, motives, and limitations. While complete disclosure isn't always necessary or appropriate, hiding relevant information or being caught in lies is incredibly damaging. Honesty, even when delivering difficult news, builds respect and trust.

- Empathy and Understanding: Demonstrating that you understand and care about the other person's perspective, feelings, and needs. Active listening and validating their experiences signals that their well-being matters to you.

- Competence: Demonstrating the skills, knowledge, and judgment necessary to fulfill your role or promises. Trusting someone requires believing they are capable of doing what they say.

- Integrity: Acting according to a set of ethical principles, even when inconvenient. Standing up for what's right demonstrates a commitment beyond self-interest.

- Benevolence: Showing genuine care and concern for the other person's welfare. Actions that demonstrate putting the other person's needs alongside or sometimes ahead of your own signal trustworthiness.

Practical Example: Think of a close friendship. Trust likely grew because your friend consistently listened without judgment (empathy), kept your secrets (integrity/reliability), showed up when you needed help (benevolence/reliability), and was honest with you, even when it was tough (transparency/honesty).

What Causes Trust Issues?

When trust is violated, the psychological impact can be profound and long-lasting, leading to pervasive trust issues. Common causes include:

- Betrayal: This is the most direct assault on trust. It encompasses lying, infidelity, breaking promises, confidentiality breaches, or abandonment. The closer the relationship, the deeper the wound. Research shows betrayal activates brain regions associated with physical pain.

- Trauma: Experiences of abuse (physical, emotional, sexual), neglect, or profound violation severely damage the ability to trust. Victims often learn the world is unsafe and people are dangerous.

- Attachment Wounds: As per Attachment Theory, inconsistent, neglectful, or abusive caregiving in childhood creates insecure working models, making it difficult to trust partners, friends, or authority figures in adulthood. Fear of abandonment or engulfment dominates.

- Personality Factors: Certain personality traits or disorders are linked to distrust. High levels of neuroticism (prone to anxiety and negative emotions) can make individuals hyper-vigilant to potential threats. Paranoid personality disorder involves pervasive, unjustified distrust and suspicion.

- Repeated Negative Experiences: A series of smaller letdowns, disappointments, or perceived slights across different relationships can gradually erode one's general willingness to trust ("Once bitten, twice shy").

- Mental Health Implications: Chronic distrust is corrosive to mental health. It fuels social isolation, anxiety (constant hypervigilance), depression (feeling alone and unsupported), and paranoia. It becomes a significant barrier to forming and maintaining healthy relationships.

Can Trust Be Rebuilt Once It’s Broken?

Rebuilding shattered trust is one of the most challenging relational tasks, but psychological research suggests it is possible, though never guaranteed. It requires immense effort, time, and commitment from both parties:

Acknowledgment and Responsibility: The trust-breaker must take full, genuine responsibility for their actions without excuses, deflection, or minimization. A sincere, specific apology acknowledging the harm caused is essential.

Transparency and Verification: The offender must become radically transparent. Willingness to answer questions honestly, provide access to information if relevant (e.g., phone after infidelity), and consistently verify their whereabouts or actions may be necessary, at least initially. This helps rebuild a sense of predictability.

Consistent Trust-Building Behaviors: Rebuilding requires a sustained, unwavering demonstration of the trust-building ingredients: reliability, honesty, empathy, and integrity – over a long period. Actions truly speak louder than words here.

Empathy and Patience from the Hurt Party: While the primary burden is on the trust-breaker, the hurt individual needs to work (if they choose to stay) on managing overwhelming feelings of betrayal and potentially challenging ingrained negative expectations. Therapy can be crucial.

Communication and Boundary Setting: Open, honest communication about needs, fears, and progress is vital. The hurt party has the right to set clear boundaries regarding what they need to feel safe moving forward.

Forgiveness (as a Process): Forgiveness is not condoning the act or forgetting; it's a deliberate decision to release resentment. It's a process, often a long one, that can facilitate healing and rebuilding, but it doesn't automatically mean trust is restored. Trust must be re-earned.

Important Note: Rebuilding is not always advisable or possible, especially in cases of severe abuse or with unremorseful offenders. Prioritizing safety and well-being is paramount.

How Does Trust Affect Mental Health?

The psychology of trust reveals a powerful bidirectional link between trust and mental health:

Trust as a Protective Factor: High levels of trust (in specific relationships and generalized) are strongly associated with better mental health outcomes. Trust fosters:

- Stronger Social Support: Trusting individuals build and maintain more supportive social networks, a key buffer against stress, anxiety, and depression.

- Lower Stress: Feeling safe and supported reduces chronic physiological stress responses. You don't constantly brace for betrayal.

- Greater Resilience: Trusting relationships provide a secure base from which to face challenges, enhancing coping abilities.

- Increased Self-Esteem: Being trusted and trusting others reinforces feelings of self-worth and belonging.

Mistrust as a Risk Factor: Conversely, pervasive distrust is a significant risk factor for:

- Anxiety Disorders: Constant vigilance for threat and suspicion fuel generalized anxiety and social anxiety.

- Depression: Isolation, loneliness, and a negative worldview ("No one can be trusted") are core features of depression. Mistrust often leads to withdrawal.

- Paranoia: Extreme distrust can manifest as clinical paranoia, believing others have malicious intent.

- Relationship Difficulties: Mistrust sabotages intimacy and connection, leading to conflict and loneliness.

The Cycle: Mental health struggles can also erode trust. Depression might make someone interpret neutral actions negatively; anxiety might fuel excessive suspicion. Breaking this cycle often requires therapy addressing both the underlying condition and the trust patterns.

The Stages of Trust Development

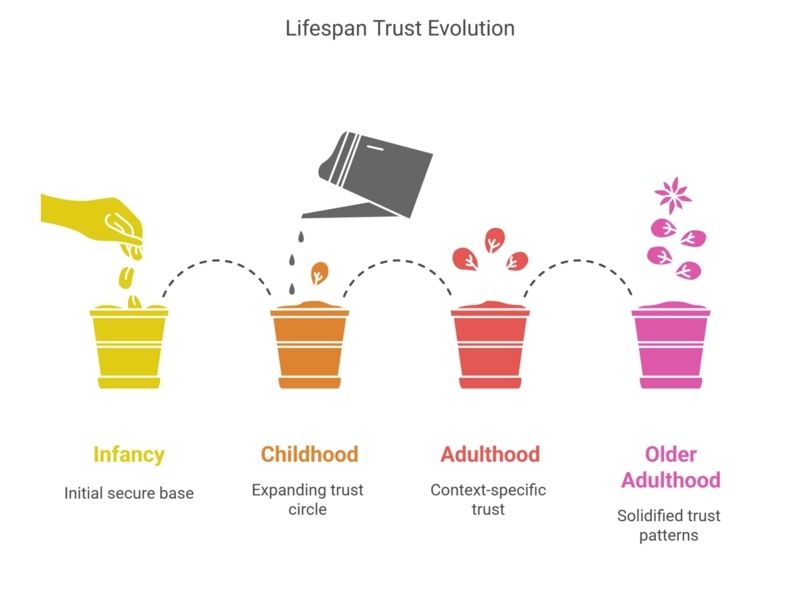

Trust isn't static; it evolves throughout the lifespan, shaped by experience:

1. Infancy & Early Childhood (Building Foundations): Based on Attachment Theory. Infants learn trust through consistent, responsive caregiving (feeding when hungry, comfort when distressed). This forms the initial "secure base" for exploring the world. Inconsistency or neglect leads to insecure foundations.

2. Childhood & Adolescence (Expanding the Circle): Trust extends beyond caregivers to peers, teachers, and other adults. Experiences with friendship, fairness, keeping promises, and peer acceptance shape expectations. Betrayals by friends or authority figures can be formative.

3.Adulthood (Complexity and Nuance): Trust becomes more sophisticated and context-specific. We learn to calibrate trust levels based on the relationship (romantic partner vs. colleague), the situation, and past experiences. We navigate deeper intimacy, professional reliance, and societal trust. Adults also have the capacity to consciously work on rebuilding trust or addressing trust issues.

4. Older Adulthood (Reflection and Consolidation): Life experiences often solidify trust patterns – either reinforcing a general sense of trustworthiness in the world or confirming earlier mistrust. However, vulnerability to scams or elder abuse can also challenge trust later in life. Maintaining trusting relationships remains crucial for well-being.

Is Trust a Feeling or a Choice?

The psychology of trust reveals it's not simply one or the other; it's a complex interplay of emotion and cognition (a dual-process):

The Emotional/Intuitive System (Feeling): This is fast, automatic, and often subconscious. It draws on gut feelings, past experiences (especially attachment history), and nonverbal cues (facial expressions, tone of voice). The amygdala plays a key role in processing trust-related threats. Oxytocin (discussed next) influences this system, promoting feelings of warmth and connection.

The Cognitive/Deliberative System (Choice): This is slower, rational, and effortful. It involves weighing evidence (past behaviour, reputation, costs/benefits), assessing risks, and making a calculated decision about whether to trust in a specific situation. The prefrontal cortex is heavily involved in this reasoning.

The Interaction: Often, our gut feeling (emotion) comes first, influenced by biology and past learning. We then use reason (cognition) to confirm, override, or refine that initial impulse based on the current context. For example, you might feel wary of a new colleague (intuitive), but consciously choose to trust them with a small task based on their credentials and your manager's assurance (deliberative). Major betrayals often overwhelm the cognitive system with intense negative emotion.

The Neuroscience of Trust: What Role Does Oxytocin Play?

Neuroscience has illuminated the biological underpinnings of trust, revealing it's not just psychological but deeply biological:

Oxytocin - The "Trust Hormone"?: Oxytocin, a neuropeptide produced in the hypothalamus, plays a significant role in social bonding, attachment, and reducing stress. Research using intranasal oxytocin administration in experiments like the Trust Game (where one player sends money to another, hoping it will be reciprocated) has shown it can increase trusting behaviour.

How it Might Work: Oxytocin appears to reduce activity in the amygdala (fear center) and dampen stress responses, making individuals feel safer and more inclined to take social risks like trusting. It may also enhance the processing of positive social cues.

Beyond Oxytocin - A Brain Network: Trust involves a complex neural orchestra:

- Prefrontal Cortex (PFC): Involved in risk assessment, decision-making, and overriding emotional impulses. The ventromedial PFC is crucial for evaluating trustworthiness based on social cues.

- Amygdala: Processes potential threats and triggers fear/anxiety responses crucial for distrust. Betrayal activates this region intensely.

- Striatum (especially the Caudate Nucleus): Involved in reward processing. Receiving trust or experiencing reciprocity activates this area, reinforcing trusting behaviour.

- Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC): Monitors conflicts, such as between a positive gut feeling and negative past experience.

The Betrayal Response: When trust is violated, fMRI studies show heightened activity in the amygdala (emotional pain, threat detection), the insula (disgust, visceral feelings), and areas involved in physical pain. This neural signature helps explain why betrayal hurts so profoundly.

Conclusion: Trust as a Psychological Superpower

The psychology of trust reveals it as far more than a simple social nicety; it's a fundamental, complex, and dynamic psychological process essential for human survival and flourishing. Driven by an interplay of deep-seated emotional responses rooted in our earliest attachments and deliberate cognitive calculations, trust shapes every facet of our lives – from the intimacy of our closest relationships to our ability to function effectively in society.

We've seen how trust is painstakingly built through consistency, honesty, and empathy, yet can be shattered by betrayal or trauma, with significant consequences for mental health. We've explored its developmental journey from infancy through adulthood and the powerful, lasting influence of childhood experiences via attachment styles. Neuroscience unveils the intricate biological dance involving oxytocin, the amygdala, and the prefrontal cortex that underpins our decisions to trust or distrust.

Understanding the psychology of trust empowers us. It helps us recognize the origins of our own trust patterns, navigate the delicate process of rebuilding after breaches, and appreciate the immense value of cultivating trust in our relationships and communities. While trusting inherently involves vulnerability and risk, it is also a profound strength – a psychological superpower that unlocks connection, cooperation, resilience, and well-being. Reflect on your own trust landscape: Where does it flow easily? Where is it guarded? How can you consciously nurture trust, both in others and as a trustworthy person yourself? In a world often marked by uncertainty, fostering trust remains one of the most powerful psychological investments we can make.

Know someone who would be interested in reading

The Psychology of Trust: Why We Believe and How It Shapes Us.

Share This Page With Them.

Go From "The Psychology of Trust: Why We Believe and How It Shapes Us" Back To The Home Page