Believing Is Seeing: The Psychology of Perception

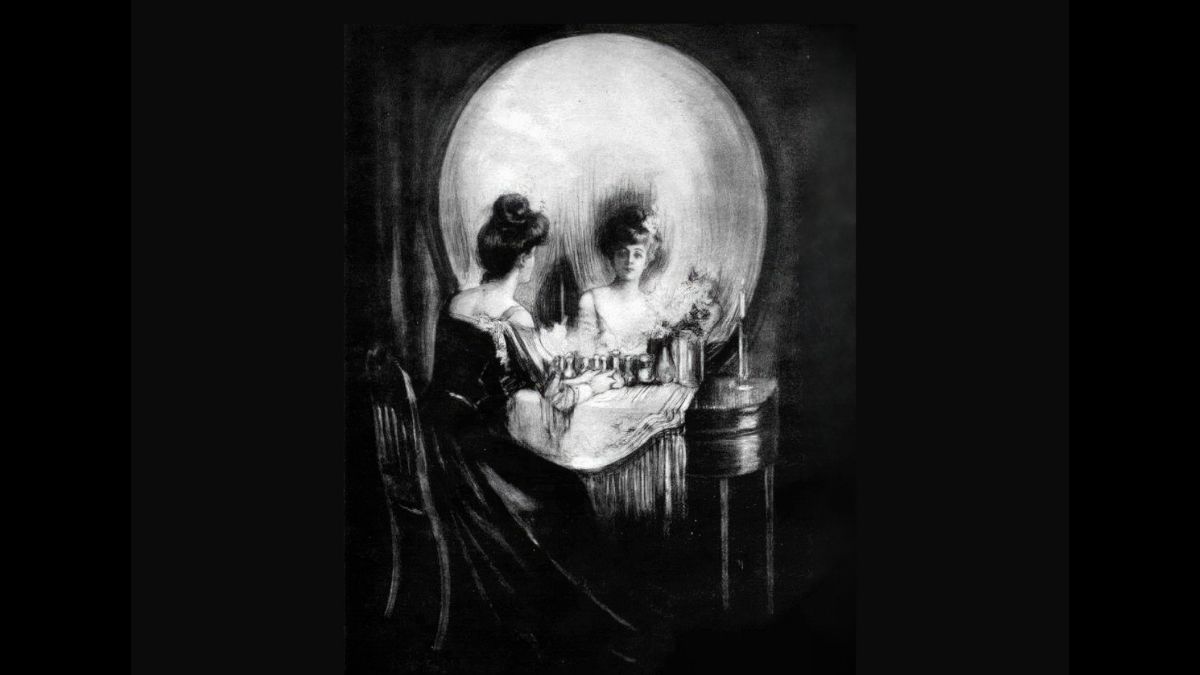

All Is Vanity (1892) by Charles Allan Gilbert. An ambiguous image that can be seen either as a woman gazing into a mirror or as a human skull.

All Is Vanity (1892) by Charles Allan Gilbert. An ambiguous image that can be seen either as a woman gazing into a mirror or as a human skull.David Webb (Founder and Editor of All-About-Psychology.com)

Most of us move through the world with a quiet assumption that we are seeing things as they really are. The scene in front of us feels immediate and direct. Light reaches the eyes, the brain registers what is there, and the world appears. It feels simple. It feels obvious.

And yet, some of the most revealing insights about human perception begin by challenging that assumption.

When Knowing Doesn’t Change What You See

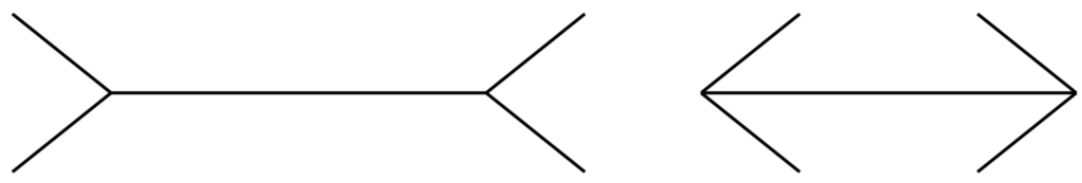

Consider the classic illusion Illusion devised by Franz Carl Müller-Lyer in 1889. Two horizontal lines appear side by side. One has arrowheads pointing outward. The other has arrowheads pointing inward. Almost everyone is convinced that the line with arrowheads pointing outward is longer than the other. Even when you are told they are identical. Even when you measure them. Even when you know exactly how the illusion works.

What makes this unsettling is not that the illusion tricks you once. It is that it continues to work even after the explanation is known. Knowledge does not undo the experience. The lines do not change, but perception insists that they do.

Perception as an Active Process

Illusions like this offer a rare glimpse into how perception usually operates. Most of the time, perception feels effortless and reliable. The brain is constantly organising shapes, judging distances, detecting movement, and identifying objects. It does this so quickly that the work itself disappears from awareness. Illusions briefly expose the process.

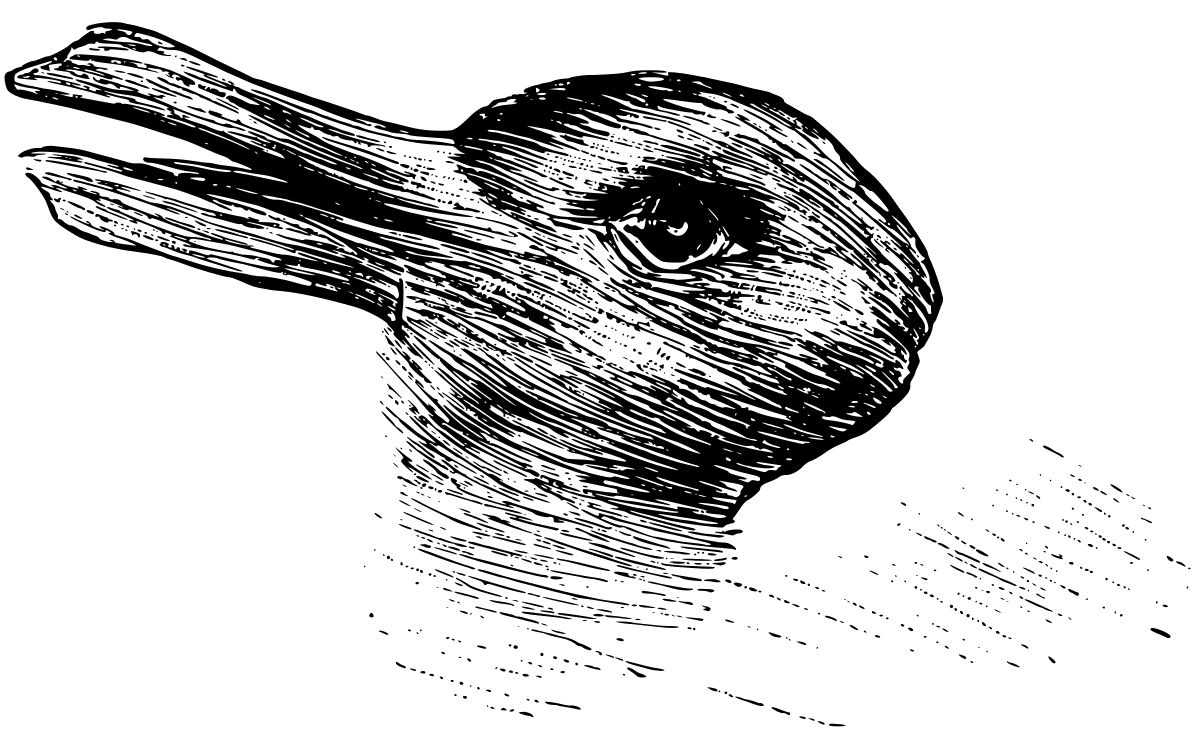

A simple drawing makes this even clearer. Take this image that can be seen either as a duck or as a rabbit. At first, one interpretation usually dominates. Then, suddenly, the image flips. The duck becomes a rabbit. Or the rabbit becomes a duck. Nothing on the page has changed. The same lines remain in the same places. What has changed is how the mind organises them.

Image from the 1899 article The Mind’s Eye by psychologist Joseph Jastrow.

Image from the 1899 article The Mind’s Eye by psychologist Joseph Jastrow.Why Attention Shapes What We Notice

These examples point to a central idea. Perception is not a passive recording of the world. It is an active process of interpretation. The mind uses context, expectation, and prior experience to make sense of incoming information. Most of the time, this works extraordinarily well. Occasionally, it reveals its own assumptions.

Attention plays a crucial role in this process. You do not take in everything around you at once. Instead, the mind selects what seems relevant and filters out the rest. For example, the following video was created by the Open University and is designed to test your powers of perception. To do the test simply click on the video play button below and make sure you’ve got the sound on your computer turned on.

This great example of inattentive blindness is an adaptation of the famous Invisible Gorilla Test by Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris, who built on the work of Ulric Neisser to demonstrate that our understanding of what we see is shaped to a large extent by where we direct our attention.

Inattentive blindness occurs because attention is limited. When the mind is focused on one task, other information can be suppressed, even when it is directly in front of us. In everyday life, this selectivity is usually helpful. It allows us to concentrate, plan, and act without being overwhelmed. But it also means that what we notice is shaped as much by our goals as by the environment.

Expectation, Context, and Everyday Experience

You can see this (no pun intended) perceptual filter at work in ordinary moments. You may rearrange the furniture at home and find that others barely register the change, or even worse, you may fail to notice your partner’s new haircut or outfit! Familiarity encourages the mind to rely on expectation rather than fresh observation.

Context shapes perception just as powerfully. A shade of gray can appear lighter or darker depending on the background that surrounds it. A face can look warm or hostile depending on posture, expression, or the situation in which it is encountered. These effects are not tricks. They reveal that perception relies on relationships rather than absolute values.

Even reading depends on this constructive process. When letters are partially obscured, misprinted, or presented in an unusual font, you usually have little trouble understanding what is written. Your mind fills in missing information automatically. You may not even notice that anything was missing or printed in error. Meaning typically emerges smoothly, without conscious effort.

Confidence, Memory, and Being Wrong

This same interpretive machinery operates far beyond simple visual tasks. It shapes how we judge situations, interpret events, and understand other people. Two individuals can witness the same conversation, the same meeting, or the same incident and walk away with different impressions. Yet their experiences can diverge in subtle but important ways.

This is particularly clear in research on eyewitness memory. People who are sincere, attentive, and confident can still recall events inaccurately. Their memories are influenced by expectations, by what they already believe, and by information encountered after the event itself. Confidence does not guarantee accuracy. The mind prioritises coherence and meaning, not perfect reproduction.

The same principle applies to first impressions. We often believe we can tell what someone is like within moments of meeting them. These impressions feel immediate and convincing. Yet they are shaped by posture, tone, context, and our own prior experiences. Once formed, they tend to guide how later information is interpreted. Evidence that fits the impression stands out. Evidence that contradicts it is often discounted or reinterpreted.

For a fascinating look at eyewitness memory, check out my interview with Professor Elizabeth Loftus, a world-renowned expert on memory, who shared fascinating insights into how our memories can be shaped, altered, and even created.

Why Belief and Seeing Are Entangled

What we expect to see influences what we notice. What we already believe shapes what feels obvious. Ambiguity is uncomfortable, so the mind resolves it quickly. It prefers a clear interpretation to lingering uncertainty, even if that interpretation is not the only possible one.

None of this means perception is unreliable or broken. Quite the opposite. The shortcuts and assumptions the mind uses allow us to function efficiently in a complex world. They help us respond quickly, recognise familiar patterns, and navigate social situations with ease. The occasional illusion or perceptual misstep is not a failure. It is a side effect of a system designed for speed and usefulness rather than flawless accuracy.

Psychology becomes especially interesting when it helps us notice these hidden processes. It draws attention to what normally goes unquestioned. It encourages us to pause before trusting first impressions and to become curious about why different people experience the same situation differently.

Once you begin to look at perception this way, you may find yourself hesitating before assuming your view is the only reasonable one. You may become more aware of how expectations shape experience. You may notice that what feels obvious often rests on invisible assumptions.

Believing, it turns out, is often part of seeing.

Two people can watch the same moment unfold and walk away convinced they saw different things. These differences are not always the result of distraction or inattention. They often occur because the world presents us with situations that are open to more than one interpretation. When a scene, expression, or image contains even a hint of ambiguity, the mind steps in and decides what the input means. It draws on experience, memory, and expectation to resolve uncertainty.

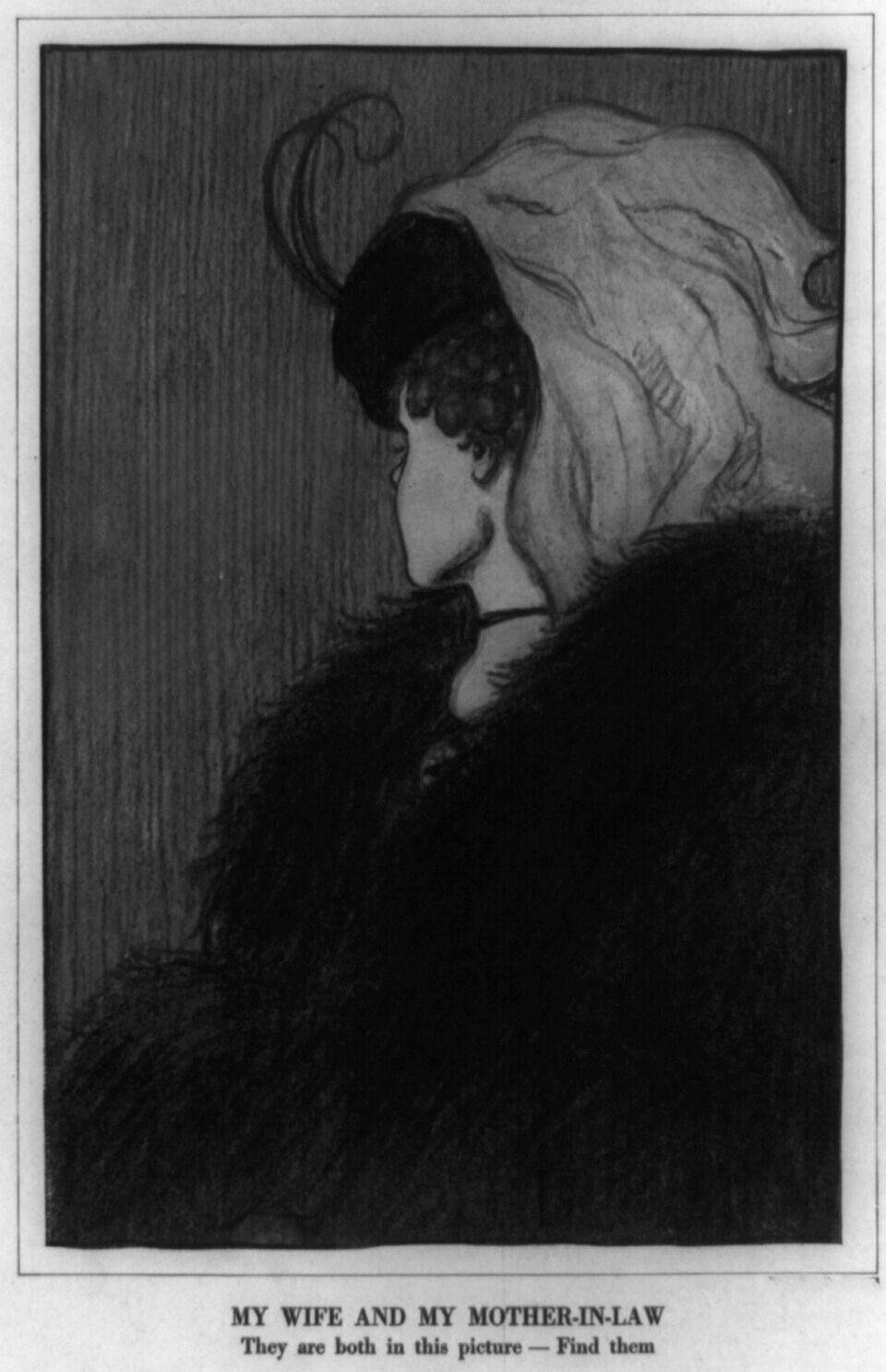

The Same Image, Two Experiences

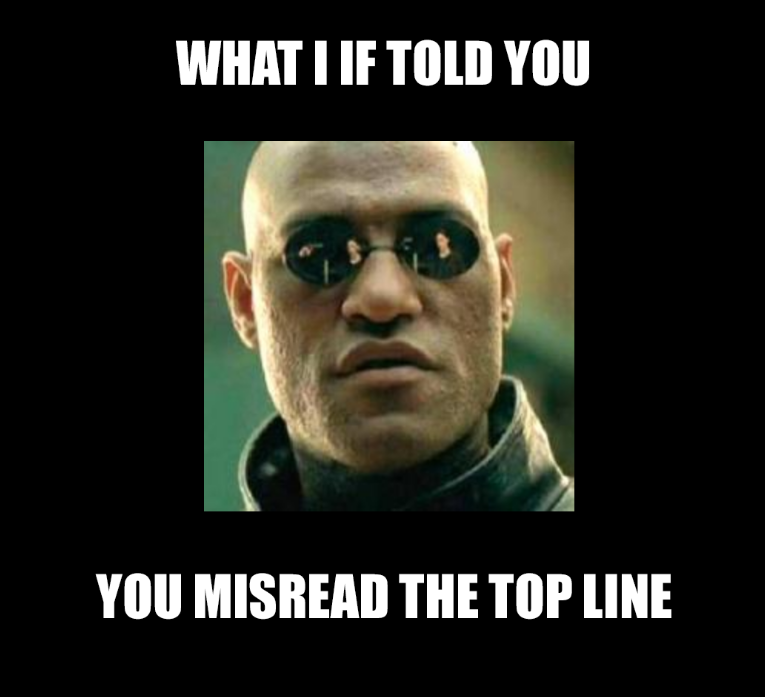

A classic example of this comes from an image that has intrigued people for more than a century. It first appeared on a German postcard in 1888 and was later popularised in a 1915 magazine illustration titled My Wife and My Mother-in-Law. At first glance, it seems clear. But what you see depends on how your mind interprets the shapes in front of you.

Some people see a young woman looking away. Others see an older woman in profile. Once you notice one version, it can take a moment to switch to the other. The drawing stays exactly the same, yet perception shifts. This happens because the image is ambiguous, and the mind must decide which interpretation fits best. The choice feels immediate, but it is influenced by the expectations and experiences you bring to the moment.

This is a clear illustration of top-down processing. Instead of relying solely on raw sensory input, the mind uses what it already knows to make sense of what it is seeing. This usually makes perception fast and efficient. It also explains why different people can interpret the same image in different ways.

Research has shown that personal experience can shape which interpretation comes to mind first. In one study, participants viewed this image briefly and reported which figure they perceived. Younger adults were more likely to see the young woman first, while older adults were more likely to see the older woman. The image itself did not change. What differed was the background of the viewers and the experiences they brought to the moment.

It’s not just images where two different interpretations can arise from the same stimulus. Imagine someone pausing briefly before answering a question. One person may interpret the pause as thoughtfulness. Another may read it as hesitation or irritation. The behavior is the same, but the meaning assigned to it differs because each person resolves the ambiguity in their own way.

Again, language and context come into play. A simple phrase like “That’s great” can express enthusiasm, disappointment, or irritation depending on tone, timing, and situation. These signals are processed so quickly that we rarely notice how much interpretation is involved.

Why Disagreements Feel So Certain

Across all of these examples, the same pattern appears. The mind uses what it already knows to understand what it encounters. This makes everyday life manageable, but it also means that people can experience the same moment differently without either being careless or dishonest.

You can see this even in straightforward situations. Two colleagues leave the same meeting. One describes a comment as supportive. The other hears it as critical. Their reactions reflect what they noticed, what they expected, and how they interpreted tone and context. They were present at the same event, but their experiences diverged.

Recognising this helps explain why disagreements about “what really happened” can feel so intractable. It is not always because someone is lying or mistaken. Often, people are drawing on different expectations and histories to interpret the same information.

Cultivate A More Curious Way of Seeing

Ambiguous illusions allow you to appreciate the fascinating nature of perception. Once you can see both the old woman and the young woman, and the rabbit and the duck, you can switch between them easily, even though nothing in the images has changed. How we see real life is more complex, but the underlying principle is the same. Perception involves choices, especially when information is uncertain.

Understanding this can soften how we respond to difference. Instead of assuming that someone who sees a situation differently must have misunderstood or is simply wrong, we can recognise that perception is an active, interpretive process. Two people can be just as attentive, sincere, and thoughtful, yet still construct different versions of the same moment. Equally, we can also appreciate that someone failing to see what seems obvious is not down to a defective character or deliberate misdirection, it may simply be because their attention was fixated elsewhere.

Perception is not a simple transfer of information from the world to the mind. It is a process shaped by experience, expectation, cognitive load and belief. When you appreciate this, differences in interpretation and how people see the world become less puzzling and more human.

For me, this is where psychology begins. Not in abstract theory, but in everyday moments that feel familiar until they are examined more closely. The science does not strip the world of meaning. It adds depth to it. It helps explain why what feels obvious is often anything but.

And it invites a different stance toward experience. One that values curiosity over certainty, and understanding over assumption.

If You Enjoyed This Article…

I’m very happy to share that my new book, Why We Are the Way We Are: Psychology for the Curious, is now available on Amazon in both paperback and eBook format.

📘 Paperback: www.amazon.com/Why-We-Are-Way-Psychology/dp/B0G4D1WJCW

📱 Kindle eBook: www.amazon.com/Why-We-Are-Way-Psychology-ebook/dp/B0G4BGR9T3

The book is a carefully curated collection of the most popular articles from this website and my Psychology Substack. If you’ve enjoyed this piece and the exploration of why we think, feel, and behave the way we do, the book brings these ideas together in one place. It also makes a thoughtful gift for anyone who loves psychology or is simply curious about what makes us tick.

If you do pick up a copy, I’d be incredibly grateful if you could leave a rating or review on Amazon. Even a short line makes a real difference. Reviews help raise the profile of the book and allow more people to discover it.

Any profit from sales goes directly toward the hosting and running costs of the All About Psychology website, which helps ensure that:

- Students and educators can continue accessing the most important and influential journal articles in psychology completely free.

- Readers everywhere can hear directly from world-class psychologists and leading experts.

- High-quality psychology content remains freely available to the public.

Thank you, as always, for reading, supporting, and being part of this community. It’s very much appreciated.

All the very best,

David Webb

Founder, All-About-Psychology.com

Author | Psychology Educator | Psychology Content Marketing Specialist

Know someone who’d enjoy reading this?

Share this page with them.

Go From "Believing Is Seeing: The Psychology of Perception” Back To The Home Page