Highly Sensitive Person: What It Means and Why It Matters

Introduction

Have you ever been told that you’re “too sensitive” or that you “overthink things”? You may belong to a group of people psychologists call highly sensitive persons (HSPs). Roughly 15–20% of the population is considered highly sensitive – meaning their nervous system is more responsive to stimuli than average. This trait, known in research as sensory processing sensitivity (SPS), is not a flaw or disorder but a normal temperamental variation. First identified by psychologist Elaine Aron in the 1990s, high sensitivity describes individuals who process information deeply, feel emotions intensely, and can be overwhelmed by a highly stimulating environment. Understanding what it really means to be an HSP is important – not only to dispel myths (being sensitive is not the same as being fragile or neurotic) but also to appreciate the unique strengths and needs of highly sensitive people in our society.

In this article, we’ll define sensory processing sensitivity and the core traits of HSPs, explore the biological and genetic basis of high sensitivity, and discuss the key advantages that sensitivity can bring in personal and professional life. We’ll also examine the challenges HSPs may face – from overstimulation to mental health risks – and how childhood environment shapes outcomes for sensitive individuals. Finally, we’ll clarify how high sensitivity differs from neurodevelopmental conditions like autism or ADHD, and offer evidence-based strategies for HSPs to thrive in school, work, and social settings. All claims are backed by research from psychology and neuroscience, with links to high-quality sources for further reading.

What Is Sensory Processing Sensitivity (SPS)?

Sensory Processing Sensitivity (SPS) is the scientific term for the innate trait underlying high sensitivity. Aron and Aron (1997) defined SPS as a temperamental trait involving “an increased sensitivity of the central nervous system and a deeper cognitive processing of physical, social, and emotional stimuli”. In simpler terms, HSPs have nervous systems that pick up on subtleties and process information very deeply. They tend to notice details and emotional nuances that others miss, and they reflect on sensory input more thoroughly before responding. High SPS is found across genders and even in other species, suggesting it is an evolved survival strategy rather than a weakness. About one in every five people scores high on measures of SPS – too many to consider it a disorder, but few enough that highly sensitive people often feel “different” from the majority.

Importantly, being an HSP is not a diagnosis or pathology. It’s a personality trait or “temperamental disposition” – much like introversion or extraversion – and it comes with both advantages and challenges. High sensitivity should also not be confused with sensory processing disorder (SPD), which is a clinical condition; HSPs generally have well-functioning senses, they just process sensory input more intensely. In fact, researchers have identified SPS as an innate trait with a genetic basis and documented it in over 100 species (from fruit flies to humans), indicating that a cautious, sensitive approach to stimuli can be evolutionarily adaptive in certain environments. In humans, the trait has gained recognition through Aron’s work, including her 1996 book The Highly Sensitive Person, and hundreds of studies since have examined how high sensitivity influences brain activity, health, and behavior.

So, what does it actually feel like to have high SPS? Dr. Aron describes a highly sensitive person as someone who “has a sensitive nervous system, is aware of subtleties in [their] surroundings, and is more easily overwhelmed when in a highly stimulating environment”. HSPs often recall feeling different even as children – perhaps they were the kid who was easily startled by loud noises, moved by music or art, or deeply upset by criticism or cruelty to others. Many HSPs are naturally empathetic, intuitive, and conscientious. However, without understanding their trait, they might grow up being mislabeled as “shy,” “anxious,” or “too emotional.” Recognizing SPS as a real, normal trait can be a huge relief for HSPs. It gives a framework to understand why they feel the way they do and how they can leverage their sensitivity in positive ways.

Core Traits of Highly Sensitive People (HSPs)

While every individual is unique, highly sensitive people tend to share a set of core characteristics. Dr. Elaine Aron uses the acronym "D.O.E.S." to summarize the four key features of the HSP trait: Depth of processing, Overstimulation, Emotional reactivity (including high empathy), and Sensitivity to subtleties. Let’s explore each of these in turn.

Depth of Processing: HSPs process information more deeply and thoroughly than others. They don’t just notice more – they think more about what they notice. Sensitive individuals have a rich inner life, often spending time reflecting on experiences, pondering meanings, and making connections. For example, an HSP student might not only read an assignment but also contemplate its implications and relate it to past material, resulting in a deep understanding. This depth of processing can lead to creative insights and careful decision-making. Research suggests that HSPs engage more brain regions related to memory and planning when processing emotional information, indicating a more complex analysis of input. The downside is that all this extra processing takes time, so HSPs may be slower to make decisions or might appear to “overthink” things that others gloss over.

Overstimulation: Because HSPs notice so much and process it so deeply, they are prone to sensory overload in high-stimulation environments. Bright lights, loud noises, crowds, chaotic scenes, or multitasking can overwhelm an HSP quickly. What seems like normal level of activity to a non-HSP can feel like “too much” input for a sensitive person. They reach a point of mental and emotional saturation sooner, leading to exhaustion or withdrawal. For instance, an HSP at a loud party might enjoy themselves for a while but suddenly hit a wall where the combination of music, conversations, and sights becomes dizzying. At that point, they may need to step outside or find a quiet room to regroup. Overstimulation is a key reason HSPs often prefer a slower pace or retreat to solitude after busy events – it’s a way to restore their equilibrium when the nervous system has been flooded. Knowing this, many HSPs plan regular downtime into their schedule to avoid burnout.

Emotional Reactivity and High Empathy: Highly sensitive people tend to feel emotions very strongly. They might tear up easily at touching music or films, feel profound joy at small positives, and also experience intense stress or heartache in response to negative events. Not only are their own emotions amplified, but HSPs are also highly empathetic – they absorb others’ feelings like a sponge. An HSP might physically cringe when seeing someone else get hurt, or feel drained after a friend dumps their emotional troubles on them, because they genuinely feel others’ pain. Brain studies confirm that HSPs show greater activation in regions involved in empathy and emotion when witnessing others’ emotional states. This emotional responsiveness can be a wonderful asset: HSPs are often very compassionate friends, attentive partners, and caring colleagues. Their high empathy helps them intuit others’ needs and build deep connections. However, it can also lead to emotional overwhelm. HSPs may struggle with strong negative emotions like anxiety or sadness, especially if they’re in a tense environment or around people who are distressed. They may need to learn boundaries so that they don’t carry the world’s problems on their shoulders.

Sensitivity to Subtle Stimuli: By definition, HSPs are keenly observant of subtleties that most others overlook. They might notice the slight shift in a teacher’s tone of voice that indicates irritation, detect a faint smell in the office that others miss, or sense the mood change in a room when a new person walks in. This heightened awareness of details extends to all senses – HSPs often have fine-tuned hearing, smell, touch, etc., and can be the first to pick up on things like a subtle change in temperature or a tiny flaw in a design. Socially, they’re very perceptive: they read micro-expressions and body language, noticing how others are feeling even when nothing is said aloud. The benefit of this trait is that HSPs can gather a lot of information from their surroundings, which can be advantageous in many situations (catching errors, spotting opportunities, or foreseeing dangers). For example, in a workplace, an HSP might be the first to sense an impending conflict in a team or the first to notice a subtle but important market trend. On the other hand, constant bombardment by subtle stimuli can contribute to the aforementioned overstimulation. Being perpetually tuned-in means HSPs have to expend effort to filter out irrelevant input, and they can be easily distracted by things (like a ticking clock or a colleague’s perfume) that wouldn’t faze a less sensitive person.

In addition to the DOES traits, many HSPs describe themselves as highly conscientious, intuitive, and driven by meaning. They often have a strong inner moral compass and may feel unsettled by environments that conflict with their values (e.g. aggressive competition or dishonesty). HSPs are frequently detail-oriented and strive for accuracy, which makes them good at catching mistakes or noticing quality issues in work. They also tend to pause and reflect before acting – a built-in caution that can prevent reckless decisions. In fact, pausing before action is considered a hallmark of sensitive temperament across species; biologists observe that more sensitive individuals (animal or human) hang back and carefully assess a new situation rather than impulsively diving in. While this can be misinterpreted as hesitancy or timidity, it’s actually a strategic thoroughness that, in the right contexts, leads to better outcomes (for example, an HSP leader might make fewer knee-jerk mistakes during a crisis because they’re naturally inclined to think things through).

The Science Behind Sensitivity: Biology and Genetics

High sensitivity is rooted in measurable biological differences. It’s not “all in your head” – or rather, it is in your head in the sense that HSPs’ brains work a bit differently. Neuroscience research over the past two decades has shown that people high in SPS display distinct patterns of brain activation and neurochemistry. In one ground-breaking study, researchers used functional MRI to scan the brains of HSPs while they viewed emotional images. They found that HSPs had significantly greater activation in brain regions involved in awareness, empathy, and self-other processing compared to non-HSPs. In particular, areas like the anterior insula and mirror neuron system (which are linked to empathic response and emotion processing) lit up much more in highly sensitive individuals. The HSP brain doesn’t necessarily perceive different things than a typical brain – but it appears to perceive more and process events more deeply. For example, when HSPs were shown photos of strangers and loved ones looking happy or sad, their brains showed stronger reactivity to these expressions than the brains of non-HSPs, indicating richer processing of others’ emotions. The effect was especially pronounced when HSPs viewed their loved ones’ happy faces – HSP brains responded with peak activation, suggesting they derive intense reward and empathy from positive social encounters. These neural findings align with what HSPs often report subjectively: greater empathy, extensive internal analysis, and sometimes sensory overload (as the brain’s sensory regions also showed heightened activity for HSPs in some studies.

Beyond brain activation, high sensitivity has a biochemical and genetic signature. SPS is considered an innate trait – one you’re likely born with. It has high heritability, as evidenced by twin studies. Molecular genetics research indicates that many genes each play a small role in conferring sensitivity. Notably, certain gene variants related to the brain’s neurotransmitters have been linked to higher SPS levels. For example, variants of the serotonin transporter gene (specifically the short/short version of 5-HTTLPR), which affect serotonin signaling, are more frequent in highly sensitive individuals. Polymorphisms in dopamine system genes and in the gene regulating norepinephrine (ADRα2b) have also been associated with SPS. These are the same neurochemical systems involved in mood and alertness, which fits with HSPs tending to have strong emotional reactions and heightened alertness to their environment. In essence, HSPs may be genetically wired to have a more finely tuned threshold for stimulation – their nerve cells amplify sensory input more than average. This notion is supported by older research (even before the term HSP existed) showing that some people have lower sensory thresholds at the neural level, allowing more signals to flood into the brain’s processing centers.

Interestingly, the high sensitivity trait is not unique to humans. Biologists have observed “sensitivity” or cautious responsiveness in many animal species. There are “bold” and “shy” fish, for instance, and some birds or primates consistently hang back to observe before engaging. This suggests that evolution has maintained a minority of sensitive individuals as a survival strategy: in certain situations, being the alert, careful observer is extremely valuable (e.g. noticing a predator or subtle changes in food availability). Human evolutionary psychologists have proposed that HSPs, with their keen perception and deep thinking, likely played important roles in early societies – perhaps as advisors, healers, or the first to sense danger and opportunity. Of course, in the modern world, we’re not usually scanning for predators on the savanna, but this trait still manifests in meaningful ways. For example, a highly sensitive person might be the first in a team to detect an inconsistency in data, or sense that a client is dissatisfied even before anything is said, thus giving a group a crucial early warning. This biological basis of SPS – spanning brain, genes, and behavior – underscores that high sensitivity is a real, tangible trait. It’s as legitimate as being tall or left-handed; you can even see it “light up” on an fMRI scan. And as we’ll see next, that wiring comes with notable strengths.

Key Strengths and Advantages of High Sensitivity

High sensitivity isn’t just about potential stress – it also bestows a range of strengths that can benefit HSPs and those around them. In recent years, psychologists and career experts have even started calling these the “superpowers” of sensitive people. Here are some of the key advantages associated with the HSP trait:

Empathy and Emotional Intelligence: HSPs typically excel at understanding how others feel. They have empathy in spades, as one research team put it. Because they emotionally resonate with others’ experiences, HSPs can be extremely caring friends, partners, teachers, or therapists. They’re often the person friends confide in, sensing they will be heard and understood. This high empathy also equips HSPs with emotional intelligence – an intuitive grasp of human dynamics. For example, an HSP manager might quickly recognize when a team member is upset or unmotivated and respond with support, defusing issues before they escalate. Studies confirm that HSPs’ brains respond strongly to others’ emotions (especially positive emotions and social rewards), which means they tend to find social connections deeply satisfying rather than dull. Many HSPs channel their empathy into constructive outcomes: they may become advocates for the vulnerable, compassionate leaders, or emotionally attuned creatives. As one article noted, this insight into others’ moods and motives can even make HSPs skilled negotiators and leaders, since they can detect unspoken needs and subtle interpersonal dynamics.

Creativity and Appreciation of Beauty: There is a strong link between sensitivity and creativity. HSPs’ depth of processing and rich inner life often fuel creative pursuits like writing, art, music, or scientific innovation. By ruminating deeply on ideas and observing subtleties in the world, sensitive people can make novel connections that others miss. Many of the world’s great artists and thinkers – from poets to inventors – are thought to have high sensitivity. Even if not in artistic fields, HSPs tend to have a vivid imagination and an appreciation for beauty and detail in their surroundings. They may be the person who notices the beautiful colors of a sunset, finds profound joy in a moving piece of music, or comes up with an ingenious solution after quietly reflecting on a problem. Research by Dr. Bianca Acevedo has noted that high-SPS individuals report greater appreciation of aesthetics and beauty, correlating with strong activity in brain areas that assign value to sensory experiences. In practical terms, this means HSPs can derive immense pleasure and inspiration from art, nature, and cultural experiences – a strength that enriches their lives and often the lives of people around them.

Conscientiousness and Detail-Oriented Work: Highly sensitive people are often described as conscientious – they care about doing tasks carefully and correctly. Because they process information deeply and notice subtle details, HSPs are less likely to rush and more likely to catch mistakes or foresee issues ahead of time. In the workplace or academics, this can translate to high-quality work and reliability. For instance, an HSP editing a document might catch grammatical nuances and factual inconsistencies that others would overlook, or an HSP engineer might diligently double-check safety features out of an acute awareness of what could go wrong. Managers have reported that employees with higher sensitivity are often among their top contributors – bringing thoughtfulness, thoroughness, and dedication to the team. HSPs also tend to have strong integrity; their empathy and depth of feeling make it hard for them to cut corners or produce shoddy work, especially if it could negatively affect others. This trait of being detail-oriented and principled can make HSPs highly valued in roles that require precision, planning, or caretaking.

Strong Intuition and Pattern Recognition: The combination of noticing subtleties and processing deeply often gives HSPs a gut sense or intuition that can be remarkably accurate. They might not always be able to articulate why they feel something is off or that a particular decision is the right one, but their hunches are often borne out by facts later. This is likely because their brains are integrating many tiny cues and pieces of past information unconsciously. An HSP might, for example, sense that a business client is unhappy even though the client hasn’t said anything overt – subtle body language and prior experiences all coalesce into a “read” on the situation. Such intuition can be a powerful guide in decision-making and creative problem-solving. HSPs are also skilled at pattern recognition: since they take in lots of data and reflect on it, they can notice trends or connections others don’t. In scientific and academic fields, this might help an HSP researcher see a meaningful pattern in experimental results; in social settings, it might help an HSP friend notice that two people in their circle would actually make a great match. Far from being “too sensitive,” their finely tuned perceptions become a source of insightful judgements and innovative ideas.

Deep Relationships and Social Skills: Although high sensitivity is often misunderstood as shyness, HSPs are not necessarily introverts (in fact, 30% of HSPs are thought to be extroverts). Many HSPs love socializing in the right settings and form exceptionally deep bonds with friends, family, and partners. Their empathy and listening skills make others feel valued, and their ability to notice subtle emotional cues can translate into excellent social skills when they are not overstimulated. For example, an HSP might be the friend who senses that you’re feeling down just by your posture on a given day – and offers support without you having to ask. They often prefer meaningful one-on-one conversations over shallow small talk, which can lead to very fulfilling friendships. In group or team environments, HSPs can act as the “emotional glue,” sensing group morale and mediating conflicts with tact. Contrary to the stereotype, many HSPs thrive as leaders or public figures if they manage their environment, precisely because they combine sensitivity with vision. They tend to lead with compassion and ethics, which can inspire strong loyalty in teams. A Psychology Today article notes that HSP qualities like diplomacy, careful listening, and tactful communication are assets in today’s business world, especially in leadership roles that require understanding diverse perspectives. In short, when their sensitivity is well-supported, HSPs can shine socially and bring people together with their authentic warmth and insight.

Challenges of High Sensitivity: Overstimulation and Mental Health

While high sensitivity offers many gifts, it also comes with some challenges that HSPs must navigate. By nature, HSPs are more reactive to their environment, which means they are more susceptible to stress when things get too intense. One major challenge is the tendency toward overstimulation, as discussed earlier. In busy or high-pressure settings – think noisy classrooms, crowded public events, hectic open-plan offices – HSPs can experience stress responses sooner and more acutely than others. They might feel frazzled, anxious, or irritable purely from the sensory load, even if nothing “bad” is happening. This is not because HSPs are weak; it’s an understandable outcome when a nervous system processes every input so thoroughly. Over time, frequent overstimulation without adequate recovery can lead to chronic stress or burnout for HSPs.

Another linked challenge is an increased risk of anxiety or mood issues under adverse conditions. Studies have found that HSPs report higher levels of things like anxious thoughts, depressive symptoms, and stress-related health problems if they are in harsh environments or have poor coping strategies. For example, an HSP who faces a very demanding, fast-paced job without any control or a supportive boss might be more likely to develop anxiety or exhaustion than a non-HSP in the same role. It’s as if the volume of life is turned up too high for too long. In relationships, HSPs can also be more hurt by conflict or criticism. A harsh remark that a less sensitive person might brush off could deeply wound an HSP, leading them to withdraw or ruminate on it for days. If HSPs grow up feeling misunderstood or told to “toughen up,” they may develop low self-esteem or chronic worry, believing something is wrong with them – when in fact their reactions are simply stronger by nature.

It’s important to emphasize that high sensitivity itself is not a mental illness and does not destine someone to have psychological problems. However, researchers consider SPS a “vulnerability factor”: in unfavorable circumstances, it can amplify the impact of stressors. For instance, some studies found HSPs in chronically negative environments showed higher rates of depression or anxiety, whereas HSPs in positive environments did not have these issues and sometimes even thrived more than their non-HSP peers. In fact, sensitivity seems to increase the range of outcomes – for better or worse (more on that in the next section). The potential pitfalls for HSPs often involve getting overwhelmed: sensory overwhelm, emotional overwhelm, and sometimes social overwhelm (feeling different or isolated). Without guidance, an HSP might fall into unhealthy habits like avoidance (e.g. isolating themselves to escape stimulation) or self-medicating (e.g. using alcohol or sedatives to calm their nerves in stimulating situations).

There are also everyday inconveniences that HSPs often mention: they might need more sleep and quiet time than others (because their system is processing so much, rest is essential), they may be more sensitive to pain, hunger, or caffeine (small physiological effects can hit them harder), and they can be emotionally exhausted by too much socializing or caregiving. Decision-making can be extra stressful if there’s a lot of stimulation or high stakes, since HSPs will mentally play out many scenarios and may get paralyzed by analysis or the fear of a wrong outcome. Additionally, HSPs sometimes struggle with assertiveness – their empathy and aversion to conflict can make it hard to set boundaries or say no, even when they are overstretched. This can lead to people-pleasing behavior that further increases their load.

Lastly, because society (in the West, particularly) often prizes being bold and thick-skinned, HSPs might face stigma or misunderstanding. They might hear well-meaning advice like “don’t be so sensitive” or get passed over for leadership roles due to the myth that sensitivity equals weakness. Such attitudes can discourage HSPs from embracing their trait. However, as awareness grows – with many articles, books, and even workplace trainings now recognizing high sensitivity – these challenges can be managed. Education and supportive communities help HSPs learn that there is nothing wrong with them. With validation, they can better address their needs and reduce the downsides of the trait (for example, by arranging more calming environments and practicing self-care, as we’ll discuss in the strategies section).

Sensitivity and Environment: The Role of Childhood and Parenting

One of the most fascinating aspects of sensory sensitivity is how much the environment influences outcomes for HSPs. Psychologists describe highly sensitive individuals as “orchids” compared to more “dandelion-like” individuals. Dandelions can grow just about anywhere with minimal care, but orchids wilt in poor conditions and bloom spectacularly in good conditions. Likewise, sensitive people seem to be more responsive to both negative and positive environments than others.

Research in developmental psychology shows that an HSP child who grows up with nurturing, supportive parenting often blossoms – they may become especially resilient, emotionally intelligent, and socially skilled because they fully absorbed the benefits of that support. On the flip side, an HSP child raised in a harsh or chaotic environment (for example, with abuse, neglect, or high family conflict) is disproportionately affected – they are at higher risk for issues like anxiety, depression, or low self-worth compared to less sensitive kids in the same conditions. In other words, sensitivity amplifies the impact of life experiences. This idea is encapsulated in theories like Differential Susceptibility and Vantage Sensitivity. Differential susceptibility suggests HSPs are more susceptible to environment quality in general (bad environments hit them harder, but good environments benefit them more), while vantage sensitivity focuses on the upside – that HSPs especially benefit from positive, enriching experiences.

A concrete example comes from a study on children’s well-being in relation to family environment: In a sample of elementary school children, researchers found that when facing multiple family adversities (such as financial problems, parental divorce, etc.), the highly sensitive children showed notably more distress and poorer outcomes (emotionally and even physically) than less sensitive children. However, when raised in very supportive families (with lots of emotional warmth and stability), the highly sensitive kids actually had better social skills and academic confidence than their less sensitive peers. The HSP kids really thrived on the extra support, showing higher social performance in positive conditions. This “for better and worse” pattern is repeatedly seen in sensitivity research.

For parents and educators, these findings underscore the importance of early environment for HSPs. A sensitive child might absolutely flourish with patient, validating parenting – their empathy and curiosity become huge strengths. But the same child, if harshly criticized or exposed to trauma, might struggle immensely, because they’re deeply processing every negative event. The good news is that HSPs can do exceptionally well if their sensitivity is nurtured. Parenting approaches like gentle discipline, predictable routines, and providing quiet downtime help sensitive kids feel secure. Since HSP children are often acutely aware of parental moods and conflicts, having open communication and reassurance is key (they will pick up on tension even if it’s unspoken). It’s also valuable to teach sensitive kids tools for emotion regulation early – for instance, how to retreat to a “cozy corner” when overwhelmed, or simple breathing exercises – so they don’t feel helpless when big feelings hit.

It’s worth noting that sensitivity is not the only factor in a child’s development; personality, intelligence, and specific life events all play a role. But sensitivity can magnify the effects of those factors. An exciting implication of this is that early interventions and positive support might yield especially large benefits for HSPs. Some researchers have suggested that in therapy or educational programs, sensitive individuals respond more strongly to the treatment – they might improve faster or more deeply internalize new skills. Indeed, a study of psychotherapy outcomes found that clients high in SPS made more progress in fewer sessions than less sensitive clients, when given the same quality of therapy. This suggests that HSPs’ penchant for deep processing and openness can work in their favor when they’re in the right hands.

For HSPs who didn’t have ideal childhoods, it’s important to know that they are not doomed. It may mean they have some extra healing to do (perhaps processing old wounds with a counselor who understands sensitivity), but their same receptivity can be turned toward positive changes at any stage of life. Many sensitive adults find that once they discover their trait and make adjustments to honor it, they experience a sort of personal growth spurt – leveraging that vantage sensitivity to transform past struggles into newfound strength and empathy for others.

Is High Sensitivity the Same as Autism or ADHD?

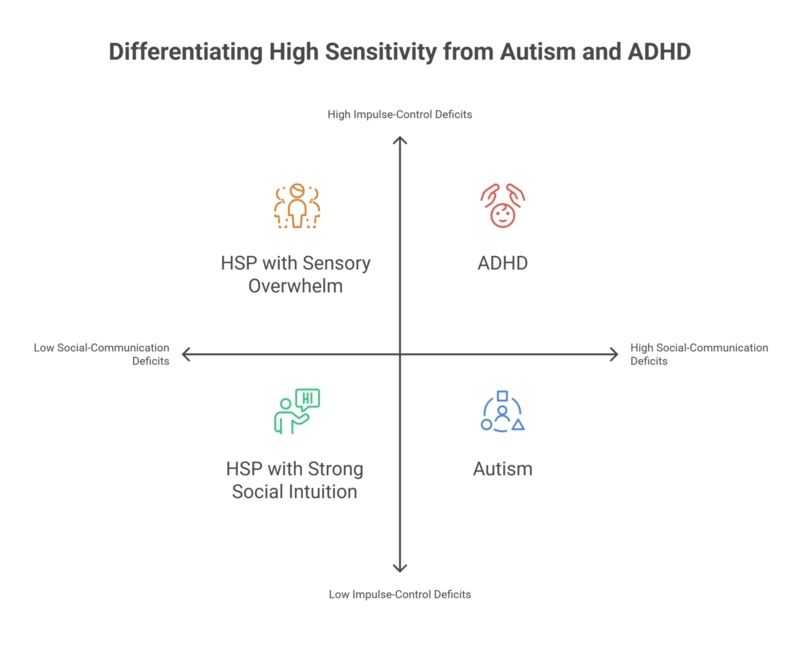

Because high sensitivity involves strong reactions to sensory input and social-emotional cues, people sometimes confuse it with neurodevelopmental conditions like autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). It’s important to clarify that sensory processing sensitivity is not the same as these conditions, though there can be some overlaps in experience. HSPs are better understood as a subgroup of the normal population (a personality trait), whereas ASD and ADHD are clinical diagnoses with specific symptom criteria.

Autism vs. HSP: Autism is characterized by differences in social communication, the presence of restricted or repetitive behaviors, and sometimes atypical responses to sensory stimuli. Highly sensitive people, on the other hand, generally do not have core social communication deficits. In fact, HSPs tend to be highly attuned to social cues, emotions, and the intentions of others. Where an autistic individual might miss subtle social cues or find it inherently challenging to interpret others’ emotions, an HSP might do this almost too well, feeling flooded by empathy or social feedback. One scientific review explicitly compared SPS and ASD and noted that autism comes with major social deficits, whereas high sensitivity does not. HSPs typically enjoy and find reward in social interaction (especially positive, harmonious interaction) – their brains show strong activation to pleasant social stimuli, like a loved one’s smile. Autistic individuals, by contrast, can find social interaction confusing or stressful, and may not instinctively seek the same level of social reward (though this varies, as autism is a spectrum).

In terms of sensory processing, both HSPs and autistic people can experience sensory overwhelm. The difference is often in the nature of the processing. Autism is associated with atypical sensory modulation – some stimuli that bother others might not bother an autistic person at all and vice versa, and autistic neurology can have difficulty filtering or prioritizing sensory input, leading to sometimes paradoxical responses (e.g. being hypersensitive to sound but hyposensitive to pain). HSPs generally have a more consistent sensitivity across senses (strong reactions to various loud, bright, or chaotic inputs) but still within the range of typical functioning – their sensory processing is just turned to a high volume, not fundamentally disorganized. Also, autism entails developmental differences that go beyond sensitivity: for example, autistic individuals often exhibit repetitive behaviors or intense special interests, which are not features of HSPs. An HSP might deeply focus on an interest due to their conscientious nature, but they remain flexible to change and don’t show the restricted behavior patterns required for an autism diagnosis.

Notably, a person can be both autistic and highly sensitive (these traits are not mutually exclusive). In fact, some autistic people with a lot of empathy and sensory reactivity might also qualify as HSPs, since HSP is a temperament trait. But many autistic people are not HSPs (they may have social difficulties without extreme sensory empathy, for example), and many HSPs are not autistic (they have intuitive social ease despite occasional overwhelm). To sum up succinctly: autism is a neurodivergent condition defined by social-communication differences and restricted behaviors, whereas high sensitivity is a personality trait defined by deep processing and high emotional/sensory reactivity. They are distinct frameworks, though an individual could potentially identify with both.

ADHD vs. HSP: On the surface, HSPs and people with ADHD might both report being easily overwhelmed or distracted in certain environments. However, the reasons differ. ADHD is marked by difficulties with executive functions: sustaining attention, controlling impulses, and regulating activity levels. An ADHD brain seeks stimulation and can hardly tolerate boredom – this often leads to impulsivity or distractibility as the person’s focus jumps around (not to mention hyperactivity in some cases). An HSP’s distractibility, by contrast, comes from too much stimulation rather than too little. For example, an HSP student in a noisy classroom might struggle to focus because they are processing all the conversations and noises in the room at once (and perhaps worrying about the emotional vibe), whereas a student with ADHD might struggle because they can’t tune out even a normal level of classroom chatter due to an internal restlessness, or they might impulsively start doodling or walking around out of boredom.

One tell-tale difference is in impulsivity: HSPs are often the opposite of impulsive – they pause and reflect before acting, as noted earlier. A hallmark of ADHD is lack of inhibition, leading to hasty actions or speech. So an HSP might be overwhelmed by stimuli but will usually withdraw or shut down to cope, whereas a person with ADHD might ramp up – getting fidgety, acting out, or seeking new stimulation to counteract feeling under stimulated or unfocused. In emotional terms, HSPs do experience strong emotions and can appear “dramatic” in their reactions, but this is because they deeply feel the events; people with ADHD can also have emotional dysregulation, but it’s often tied to impulsivity (quick anger, frustration tolerance issues) and not necessarily accompanied by the same depth of sensory reflection.

Another difference: ADHD is typically evident from childhood as a pattern of functional impairments (school difficulties, etc.), and it often requires clinical intervention or medication to help the individual function in a neurotypical world. High sensitivity might also be noticeable in childhood (the child who cries easily or needs alone time), but it does not inherently cause impairment – many HSPs function well once they learn to manage their needs. In fact, being highly sensitive can come with excellent attention to detail and focus in comfortable settings, whereas ADHD is a persistent challenge with attention across settings. That said, it’s possible for someone to have both traits: an HSP with ADHD might deeply feel things and have trouble with executive focus. But in general, HSPs do not have the cognitive impulsivity that defines ADHD, and their distraction is situational (stemming from environment overload) rather than an always-on difficulty in regulating attention.

To summarise, high sensitivity is sometimes colloquially likened to being “slightly autistic” or “having a bit of ADHD,” but these comparisons are misleading. HSPs do not have the social-communication deficits of autism nor the impulse-control deficits of ADHD. What they do share are certain surface behaviors (like avoiding busy environments, which an autistic person might also do, or struggling in loud classrooms, as an ADHD person might as well). It’s crucial for professionals and individuals to distinguish these, because an HSP does not need the same interventions as an autistic or ADHD person. An HSP who is misdiagnosed with ADHD might be given stimulant medication unnecessarily, for example, when their issue was not inattention but sensory overwhelm. Likewise, an HSP child might be wrongly evaluated for autism due to sensory sensitivities, when in fact they have strong social intuition and just need help handling stimulation. If there’s any doubt, a thorough assessment by clinicians (who are aware of SPS as a trait) can clarify the profile. Many psychological tests and questionnaires can differentiate whether someone’s challenges align more with a disorder or with the typical range seen in HSPs

Thriving as a Highly Sensitive Person: Strategies for Success

Being an HSP in a fast-paced, often overwhelmingly stimulating world can be challenging – but with the right strategies, highly sensitive people can thrive in any domain. The key is for HSPs to proactively manage their stimulation levels, practice good self-care, and leverage their strengths rather than apologize for them. Whether in school, work, or social life, small adjustments can make a big difference in turning high sensitivity into a superpower instead of a liability. Here are some research-backed tips and strategies for various areas:

Optimizing Your Environment: HSPs are heavily influenced by their surroundings, so crafting a suitable environment is fundamental. Whenever possible, reduce excessive stimuli in your daily environment. For example, if you’re studying or working, try using noise-cancelling headphones or soft earplugs to buffer loud noises. Dimming harsh lighting or using natural light can also prevent sensory fatigue. At home, designate a low-stimulation space where you can recharge – perhaps a quiet room or a cozy corner with soft lighting and minimal noise. This could be where you retreat for a few minutes when you feel overwhelmed. Even in busy workplaces or schools, find small ways to create “sensory breaks” – stepping outside for fresh air, closing your eyes for a short meditation, or even retreating to a restroom or empty conference room for a couple of minutes of silence can help reset your overloaded senses.

Time Management and Downtime: HSPs do best when they pace themselves. This means not packing your schedule to the brim without breaks. If you are a student, avoid back-to-back hectic classes all day if you can – allow a free period or a quiet lunch in the library to decompress. In the workplace, make sure to take your lunch break (don’t work through it) and use it as a sensory break – perhaps take a walk outside or eat in a peaceful spot rather than a noisy cafeteria. Learn to say no or set limits on extra commitments; for instance, if you know that socializing two nights in a row drains you, it’s okay to decline that second invite in favor of rest. Scheduling “downtime” each day – whether it’s an hour of reading, a warm bath, listening to calming music, or simply doing nothing in a quiet room – is crucial for HSPs to process the day’s rich input and prevent burnout. Think of these as essential maintenance for your finely tuned system.

Self-Advocacy and Boundaries: Educating the people around you about your needs can greatly improve your experience. Many HSPs feel shy about disclosing their sensitivity, but you don’t necessarily have to label yourself an HSP if you’re not comfortable – you can simply communicate your preferences. For example, you might tell your coworkers, “I concentrate best with fewer interruptions, so I’m going to put my headphones on for an hour to focus.” Or let your friends know that you’ll join the afternoon outing but might skip the loud evening pub, suggesting a quieter get-together next time. In academic settings, advocate for minor accommodations if needed: some HSP students benefit from taking exams in a smaller quiet room (to avoid the stimulation of a big hall) or from sitting in the front of class (to minimize the visual distraction of everyone in front of them). Many schools and workplaces are increasingly open to flexibility, especially when framed as improving productivity. Don’t hesitate to ask for what helps you – whether it’s a desk farther from a noisy doorway, the ability to work from home one day a week, or a bit of extra transition time before moving on to a new task. Framing it in terms of doing your best work can help others see the request as reasonable. Remember, your sensitivity is not an embarrassment; it’s a legitimate trait with specific needs.

Emotional Self-Care: Because HSPs feel so deeply, it’s important to have outlets and practices for emotional regulation. Mindfulness and relaxation techniques can be very beneficial. Practices like deep breathing exercises, meditation, or gentle yoga can help calm an over-aroused nervous system and center your mind when emotions run high. Even a short breathing break (e.g., 5 slow breaths) in the middle of a busy day can reset your stress level. Journaling is another tool many HSPs find useful – writing out your feelings and thoughts can provide relief and insight, allowing you to process that depth of emotion in a structured way. Engaging in creative hobbies – whether painting, playing music, or gardening – can also serve as a healthy emotional outlet, converting intense feelings into art or nurturing activities. Additionally, be mindful of media consumption: HSPs can be strongly affected by violent or distressing media. It’s okay to curate what you watch or read (for example, limiting negative news binges or skipping that ultra-violent TV series everyone is talking about) to protect your emotional well-being.

Leverage Strengths in School and Work: Rather than trying to fit a non-HSP mold, use your trait to your advantage. In academics, your thoroughness and keen observation can lead to top-notch work – for instance, you might excel in research projects, writing detailed papers, or engaging in thoughtful class discussions. Choose study methods that align with your style: you might prefer to study in a quiet, aesthetically pleasing environment and delve deeply into material, rather than in a raucous group. In group projects, you could take on roles that involve planning, editing, or quality control, where your conscientiousness will shine. In your career, seek out (to the extent possible) work that aligns with your values and zone of genius. HSPs often thrive in roles that require creativity, empathy, or attention to detail. They make excellent counselors, teachers, writers, designers, researchers, quality analysts, etc. – any position where their careful processing and insight is an asset. Even within a less-than-ideal job, find niches where you can do things your way. For example, if brainstorming meetings are overwhelming, perhaps you can contribute by writing up your creative ideas afterward once you’ve had time to process. Many HSPs do well with mentors or coaches who understand their temperament; don’t hesitate to seek guidance on how to navigate career challenges as an HSP. And celebrate your wins: when your boss praises your detailed report or a friend thanks you for your understanding ear, recognize that it’s your sensitivity at work as a strength.

Social Strategies: While HSPs love meaningful connections, they may have social limits. One strategy is to prefer smaller gatherings or one-on-one hangouts over large, loud parties (at least most of the time). You’ll likely find these settings more fulfilling and less draining. If you do attend big events, give yourself permission to take breaks – stepping outside for a breather or finding a quiet corner for a few minutes can prevent complete overwhelm. It’s also perfectly fine to have a “French exit” (leaving without fanfare) when you’ve had enough social time; your true friends will understand. Build a support network of people who appreciate your sensitivity. Spending time with fellow HSPs or at least friends who are gentle and validating can recharge you, as opposed to those who might mock or dismiss your needs. Educate close friends or family members about what high sensitivity really means (perhaps share an article or two). When they see that your reactions (like needing downtime or being upset by violence) are part of a real trait, they may be more accommodating. Finally, don’t feel guilty for prioritizing self-care in social life. HSPs sometimes worry they’re being antisocial if they skip events. But striking the right balance ensures that when you do show up, you’re able to be fully present and enjoy the interaction, bringing the best of your empathetic, thoughtful self.

Professional Help When Needed: Sometimes, despite best efforts, an HSP can struggle with anxiety, depression, or just navigating a world that feels very intense. Therapy or counseling can be extremely beneficial – ideally with a therapist who is knowledgeable about high sensitivity. In therapy, HSPs often find relief in simply being understood, and they can learn tailored coping skills (like how to reframe negative thoughts that plague them, or how to gradually increase tolerance to necessary stimuli). Interestingly, research indicates that HSPs may respond especially well to therapy since they’re so receptive to input. Even short-term therapy or a support group for HSPs can equip you with new tools and confidence. There are also many books and online communities now for HSPs, offering tips and camaraderie – knowing you’re not alone can be empowering.

Thriving as an HSP isn’t about trying to become less sensitive; it’s about honoring your sensitivity while setting yourself up for success. By structuring your life in HSP-friendly ways and using your natural gifts, you can turn what some see as a liability into a true asset. As one Medical News Today article summarized: with the right environment and habits, HSPs often feel less overwhelmed and are “empowered to work toward positive outcomes, such as using their empathy to better understand people and foster meaningful relationships”. In fact, many HSPs eventually come to view their sensitivity as a valuable part of who they are – a source of depth, connection, and creativity that enriches their lives and the lives of others.

Know someone who would be interested in reading

Highly Sensitive Person: What It Means and Why It Matters.

Share This Page With Them.

Go From "

Highly Sensitive Person: What It Means and Why It Matters

" Back To The Home Page